Peter Brook‘s “King Lear” occupies a barren kingdom frozen in the middle of a winter that chills souls even more than bodies. He is not his own master: he gives away his power and then discovers, with a childlike surprise, that he can no longer exercise it. Burdened by senility and a sense of overwhelming futility, he collapses gratefully into death.

It is important to describe him as Brook’s Lear, because he is not Shakespeare’s. “King Lear” is the most difficult of Shakespeare’s plays to stage, the most complex and, to my mind, the greatest. There are immensities of feeling and meaning in it that Brook has not even touched. And for Shakespeare’s difficulties of staging, he has substituted his own cinematic decorations.

This is not to say that his film, which arrived here unheralded a year after its New York premiere, is not a brave and interesting effort in its own right. Peter Brook is not constitutionally able to direct “screen versions” of someone else’s work. The vision must be his own, even if that means Shakespeare finishes second; this is not so much a film of “King Lear” as a film about it, with Brook’s critical analysis of the play suggesting his directorial strategy.

His approach was suggested by “Shakespeare Our Contemporary,” a controversial book by the Polish critic Jan Kott. In Kott’s view, “King Lear” is a play about the total futility of things. The old man Lear stumbles ungracefully toward his death because, simply put, that’s the way it goes for most of us. To search for meaning or philosophical consolation is to kid yourself. Kott attempts to transform Shakespeare into a sort of Elizabethan John the Baptist, sent ahead into the world to announce the coming of Beckett.

I suppose every age has attempted to redefine Shakespeare in terms of its own preoccupations, and the Brook-Kott version of “Lear” is certainly fashionable and modern. But it gives us a film that severely limits Shakespeare’s vision, and focuses our attention on his more nihilistic passages while ignoring or sabotaging the others.

There is a great deal of goodness in “King Lear.” There is the old king himself, “more sinned against than sinning,” whose cruelties are the result of misplaced love. There is Cordelia, the most touchingly sincere heroine in all of Shakespeare. There is Edgar, totally devoted to the father who has disowned him, and Kent, who serves Lear out of love. And there are the moments when Lear shakes off his sense of doom and hurls taunts at the gods, or tells his beloved Cordelia that their suffering will pass and they will once again live like songbirds and dabble in the gossip of the court.

Lear even seems to die convinced that Cordelia lives; she does not, but his last conscious impulse is one of hope and faith. Perhaps that is Shakespeare’s final thought: that the ability to hope is what makes us human, even if, in fact, our hopes are futile.

This is a great and humanistic assertion, and it has no place in the Peter Brook film. He omits or rearranges dialogue and scenes in order to make the evil daughters, Regan and Goneril, ambiguous in the villainy. He gives us a Cordelia who is not as perfect as she should be. He gives us a Lear who is only a figure of pity, not (as he was in Shakespeare) also sometimes a figure of greatness. He gives us a world so grim we might as well be dead.

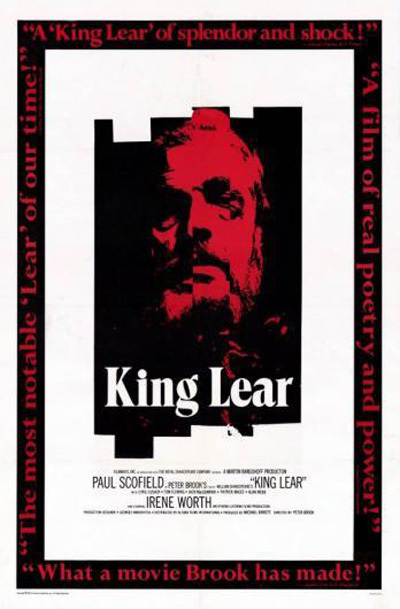

Lear is played by Paul Scofield, whose beard and large, sad eyes make him look distractingly like the middle-aged Hemingway. Perhaps because of Brook’s direction, Scofield’s readings are often uninflected and exhausted. He reads Shakespeare’s poetry the way Mark Twain said women use profanity: “They know the words, but not the music.” The acting style suits Brook’s ideas about the play, but leaves Lear diminished as a character.

As so many art films seem to, “King Lear” came to Chicago without advance notice. Hopefully, it will not leave without warning. But while it is here, what use can we make of it? A high school English teacher called me Friday to ask if she should send her students; I hadn’t seen the movie and didn’t know. Now I think the answer is yes, and precisely because this isn’t a faithful movie version of a classic.

Shakespeare’s Lear survives in his play and, will endure forever. Brook’s Lear is a new conception, a rethinking, and a critical commentary on the play. It is interesting precisely because it contrasts so firmly with Shakespeare’s universe; by deliberately omitting all faith and hope from Lear’s kingdom, it paradoxically helps us to see how much is there.