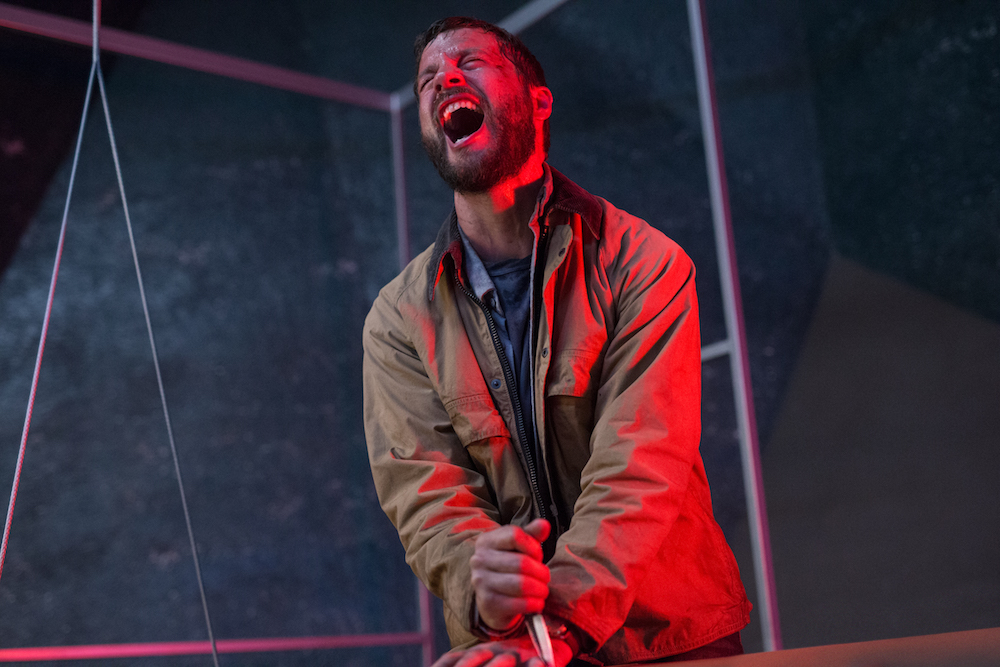

A tight-fisted sci-fi film conceded with technology’s invasion into our well-being, “Upgrade” is about a man who receives a secret experimental computer chip after he is paralyzed in the same incident that killed his wife. A chip known as STEM is able to control his bodily functions—with his permission—and turns him into a super-fighter when necessary. Logan Marshall-Green plays Trey, the man-turned-machine in question, who is trying to hunt down who killed his wife, while evading a detective (Betty Gabriel of “Get Out“) who doesn’t know of his new condition.

Drawing inspiration from films like “The Terminator” and “The Raid,” while having a refreshing focus on action with fight scenes that show Marshall-Green fighting robotically like a computer “John Wick.” “Upgrade” is the product of none other than writer/director Leigh Whannell, who is no stranger to challenging genre expectations on a tight budget (as with the franchise-starters “Saw” and “Insidious“), and has a fascinating history of working within Hollywood but not seeking to make considerably larger films.

It’s not that Whannell couldn’t make a larger action film, something that “Upgrade” proves in more ways than one. But it’s a very interesting contrast from his close collaborator on those earlier films, James Wan, who went on to direct “The Fate of the Furious” and the upcoming “Aquaman.” But as Leigh and I talk about “Upgrade,” Whannell proves that his genre visions are more expansive than just having a bigger budget. In the interview below, we also touched how “Upgrade” has a better look than “Solo: A Star Wars Story,” how gaffer tape in “Looper” inspired “Upgrade'”s production design, his penchant for checking Twitter for “Upgrade” hot takes and more.

Welcome to Chicago, Leigh.

The longest time I’ve ever been in Chicago is … before I had kids, I used to do this thing where if I was writing a script or it was in the early stages, I would fly to a random city that I’d never been to or that I hadn’t spent [time] and just book a hotel room. I’ve actually met other screenwriters who do the same thing. You never meet other screenwriters because it’s such a lonely profession. I did it so many times and I would spend about a week. What I would do is spend the whole day in the hotel room writing, and then at night I would go out and get something to eat and walk around.

For the first draft of this movie, I came here and stayed on [Michigan Ave], I forget which hotel it was. It was the middle of winter, and I remember every morning I would look out my room and there was this thick, white, that cloud that settles in. But I loved it. I think of “Upgrade” as a very noir film, and it felt very noir-y to me, walking around Chicago at night with the elevated train. I was really like, not to sound too wanky, like method writing. I’m gonna method write this one. I took all these photos, I wish I had my laptop so I could show you all the photos.

That’s funny you mention other writers, because I noticed Simon Barrett’s name in the “Thank You” section for the closing credits. This movie has a vibe like his previous script, “The Guest.”

Yeah.

Did you guys talk about “The Guest” at all?

Yeah, well he actually lives down the street from me in Los Feliz in Los Angeles. He’s close by, and him and [“The Guest” director] Adam Wingard have become friends of mine. It’s interesting in LA because there’s a horror community of horror filmmakers, but it’s fractured. It’s kind of clique-y in some ways.

What’s the definition of your clique?

I’ve realized that I don’t have one. It’s basically me, Adam Wingard and Simon Barrett, we’re like the three “Sandlot” kids, the losers over there in the corner. And he’s a good friend. I like catching up with Simon because he’s got a lot of opinions, we can just talk for hours about stuff. And he was getting involved with this film, and the reason that I gave him thanks is that he read a draft of the script, and then he saw an early cut of the film.

But it’s interesting that you mention “The Guest,” because I think it was an influence. I actually saw that film before I knew those guys. I got to know them by–it’s a classic 2010 story. I DM’d them and said “I loved your movie ‘The Guest,'” and we ended up catching up over drinks. But I remember seeing that movie in the theater and really responding to that Carpenter-esque, fun genre. As soon as that title card comes up in the Carpenter font, I knew I was in for a good time. And I think it was an influence because if you look at “The Guest,” it’s kind of a low-budget genre film but it’s aspiring to be this kind of sci-fi action film. A lot of low-budget genre films you see are horror movies, because horror is the friendliest movie to lack of money. But “The Guest” has machine-gun fights. I really think you’re right there, I think it was a big influence on the film.

Speaking of horror and budget, “Upgrade” seems to languish on that low budget, as well. Do you find, especially with how you started with something like “Saw,” that you languish with a lower budget? Or are you working towards larger expensive projects?

The thing I love the most about low budget films is the creative freedom. The fact that they don’t really have time to ask you a zillion questions, even if they want to. Big studios have the money to prolong these development periods, and they pay for the right to do that. They’re like, “ah, you want to complain about my notes? How about this check? Will that cure your complaints?” Whereas Blumhouse is like, “Ah, I’ve seem to have lost my checkbook … how about we just shoot it as is?” [laughs] I like the immediacy of that, when you’re getting the notes to the script, you know that the shooting of the film is not three years away, that they’re not going to shelve it. It’s something that is actually going to happen, there’s kind of a forward momentum at Blumhouse that low budgets give me, and I’m kind of addicted to that forward momentum. I’ve done one film with a proper studio, and it was that very prolonged period with two years later it was like, “So, are we making this, or?” And while I just keep churning out drafts, “is this the seventh circle of hell? Am I dead and I don’t know it?” [laughs] I do think that is attractive to me because what you end up with is your film, and so there’s certainly not a burning desire for me to go and do a big tentpole movie. I think a lot of people think that desire is a given. I’m not using “Upgrade” as a ladder to something.

If you wanted, you could.

Exactly. Even my own agent is like, “Of course, right? You want to move out of the slums? Right? Get an apartment on the Magnificent Mile?” There’s a real assumption on the part of everyone that ascension is the goal, and I think people are kind of mystified when you want to make lateral moves. Like, “You want to make another low budget film? Do you know that Marvel is actively looking for directors?”

I think what do happens is that the flattery of being asked to do one of those movies is probably overwhelming, that phone call. You can stand there all day and say, “I do NOT want to make one of those … hello? Do I? Yes I do.” [laughs] I think you get drunk from the flattery of that. So, in short, who knows what I’d say if that phone call came. But right now, I think I’m keen to keep exploring this little niche of trying to achieve champagne on a beer budget.

You and James [Wan] started together but have gone in completely different directions. How does he rationalize that to you? Are you guys still friends? He’s in the movie and the “Thank You” section in the credits as well.

Yeah, he was there, and I definitely asked him for advice. I remember in the middle of his busy schedule of editing “Aquaman,” I dragged him out to lunch and was like, “Ok. How do I shoot a car chase?”

He’s done a few.

Yeah, he’s done a movie that was all car chases. And so it was interesting to be sitting in this Mexican restaurant in LA, and him grabbing the salt shaker and being like, “OK, you really want to shoot low, because you want to be looking up at the cars.” So he gave me his tips on that, and it’s great to have that involvement. But in terms of where he’s gone, he’s always wanted that. Like, the first day I met him at film school, it’s that nervous first day of university when you’re meeting everybody. There was a circle of us in some food court. Everybody else–it’s film school–was like, “I’d love to make something like Wim Wenders’ early work …” and James was totally unashamed to say, “I want to be James Cameron. That’s what I want to do.” And of course everyone is [coughing sounds]. But watching him make these huge movies is like watching him get to the place he always wanted to be, which is not so the case with me.

But you want to make those kind of “lateral moves.” And this movie is based on the the challenge of what you have, what’s inside the box.

As a kid in the ’80s, you’d go to the video store and all of the sci-fi movies lived in that box. Before the advent of CG in the early ‘90s, you probably also remember that watershed moment when “Jurassic Park” came out, and people were going to see the movie just to see that moment, it was like a civic duty to go see that dinosaur movie, and it was like “Whoa.” It was like one more step, it was the monkey throwing the bone in “2001,” like, “Oh my god, the medium of film just took a step.” But prior to that, it was the height of practical effects, so that give birth to things like “Robocop,” “Total Recall,” “Terminator,” that era of sci-fi movies that sort of had to live within this area.

And I do find these days that the huge CGI extravaganzas, there is a slight numbing effect, because if you can do anything, nothing means anything. With those films that lived within that box, they had to get really creative with the way they presented the science-fiction. “Robocop” shot in Dallas because Dallas had slightly futuristic-looking buildings back in ’87 [laughs]. That to me is an example of how that production had to get creative with the future. I really used those movies as the inspiration for this. this is the watermark of what we’re trying to do with [“Upgrade”].

I have to say that I saw “Upgrade” right after “Solo: A Star Wars Story”, and your film looks so much better. The cinematography in “Solo” is very bad. It’s really filtered and washed out. “Upgrade” was very refreshing in that way.

Do you think it’s something they have gone for deliberately, like let’s go for this look?

Kind of, but it really numbs the image.

Is it a retro thing maybe?

It’s not like how they light previous films. Nothing pops. It’s very drab. And [cinematographer] Bradford Young …

He’s an amazing.

It’s tragic.

It’s not a guarantee that giant budget is going to look perfect. It’s a guarantee of color and movement and noise, but it’s not a guarantee of this seamless transition. I wanted something really tactile.

A modern example of that for me is something like “Looper.” I thought “Looper” … I loved the lived-in feel. Remember when he walked into the place where all the loopers hung out, and you had to put your gun in a box? Everything was so greasy. I remember one piece of production design that I really zeroed in on when thinking about “Upgrade” was the box that you put your guns in was just kind of gaffer taped to the wall. And I think a lot of future-set movies, just as an automatic go-to, they go a bit shiny. Of course everything is going to be cleaner and nicer in the future. And they’re not going to stop using gaffer tape to stick things down that fall. So I really zeroed in on that, and said to the DP of the film, “You see that bit of gaffer tape?” And he’s like, “Yeah.” “I want floral lights, shitty ones, that blink on and off. Dirt smudges,” and I think there’s a tendency … see this stuff? [pointing to some scuff marks on the wall]. This is what I wanted, and there’s a tendency with production designers, especially if the movie is in the future, to make this shiny. and I said, “No, no, no. Leave this stuff.” And then there’s certain sets where we went a bit future-y, Apple Headquarters.

But it’s good when you say you notice stuff like that. You realize that in cinema, even the tiniest detail registers in the audience’s eye. The information goes in, even if they’re not consciously looking and noticing the piece of tape or that mark; the human eye and brain is able to process it and push it to the back. So it’s been a good lesson for me, this movie, in how much people notice. Even the little things that you never thought people would notice in a million years, they’ll bring up.

Or, if they notice it and it seems wrong, it will take them out. When you think of audience are you thinking about that as well?

Yeah, I really am. And you know what’s funny, is that you’re really taking reviews into account. I notice when you read interviews with directors, I hear a lot of things like, “You know, you can never read reviews. If you believe the bad ones, you’ll start to believe the good ones,” or something like that. And that sounds like a really healthy policy. But I feel like it’s an impossible task to put something out into the world and then ignore the world’s feedback. And in the most direct form of that feedback are reviews, and I guess now in the social media age you can get direct feedback from audiences. I’m definitely, I’m not going to lie to you, straight after every screening I’m scanning Twitter.

You’re going to get tagged so much more, now.

Yeah, Zombiegirl15 in the suburbs of chicago. I want you to know that I read your tweet. You think you’re shouting into the void, but I read it. And it hurt! It hurt when you said that “Upgrade” was predictable. [laughs]

It all goes in, and I think you end up filtering that. So when you ask about the audience, I definitely sit there and I go, “I’m in the audience, watching this movie, what’s going to be the thing that takes me out?” You mentioned the camera work with the locking to the actor, that was something that we had to calibrate. What is the point where somebody goes, “Ah, this movie is giving me vertigo! I hated the fight scenes.” There have been certain friends of mine and critics, without naming names, who have said about other films, “God, the fight scenes made me dizzy.”

Like the Jason Bourne movies.

Yeah, it’s like, put it on your shoulder! [laughs] Who’s punching who? Wait, he won?

You have some very clean action in “Upgrade.” I don’t know if “John Wick” was a direct influence but it looks like it.

I like pointing the camera at the actors and letting them fight. Don’t let the camera do the fighting for you, and don’t let the camera give them the adrenaline hit. Let the people in the frame do that. Which is tough. I think if you’re doing “The Raid,” you have these amazingly trained actors. We didn’t have that. So it was like, “How do we do ‘The Raid’ without their stunt team?” So we tried our best, and that little camera locking technique, where we actually strapped an iPhone to Logan under his clothes, and the camera locks to the phone, so whichever way Logan moves. So if he bends backwards, the camera will go with the phone, so it’s quite simple. It’s all done in camera. And the trick was “What’s too much?” I don’t want want to make everyone sick if the camera’s doing this, but it’s just a matter of fine-tuning. Here’s a little sprinkiling of it, and we’ll come back to it.

The camera recognizes the iPhone?

The center of the camera locks to this app, and you turn it on, and I put the phone under your clothes, strap it on, and when I’m holding the camera housing, it will do what you do. The camera will follow. It’s a really weird technique, but I think when you apply it to fight scenes, it’s good.

You said you didn’t have Raid actors, but you could have convinced me otherwise. The choreography is so clean, and the camera is so focused.

Well, that’s another lesson going into the next film. When you think you may be lacking in something when making a film, if you make a film right you’re actually not lacking it. If you make the film right, if you do your job, people won’t be saying, “Well, he didn’t have ‘The Raid.'” They’ll go with it!