By Roger Ebert

John Sayles is the living legend of independent film. He and his life partner, Maggie Renzi, have made 19 features entirely on their own terms. To finance them, Sayles has written, rewritten or ghostwritten screenplays entirely on the terms of others, from “Piranha” to the forthcoming “Jurassic Park” sequel. Their latest film, “Honeydripper,” is set at the junction of rhythm & blues and civil rights in the 1950s South, and is getting some of his best reviews.

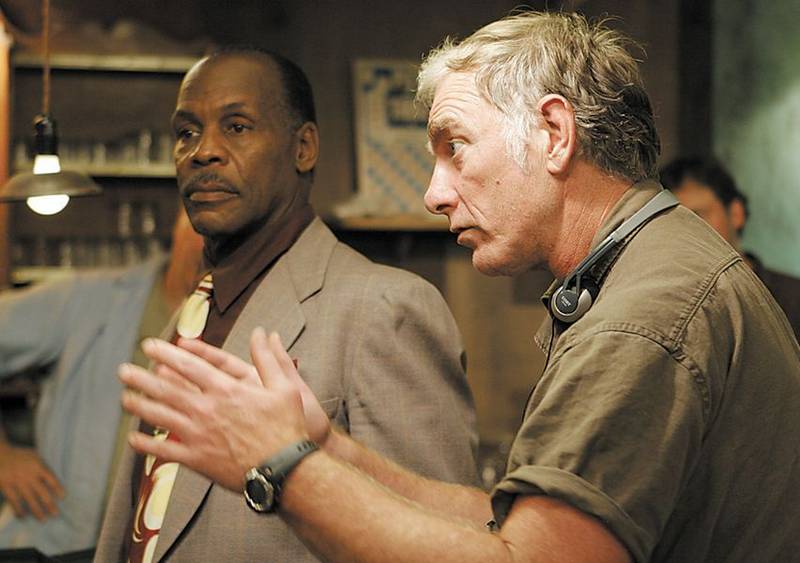

The movie stars Danny Glover as the operator of a club in Harmony, Ala.; Charles S. Dutton as his best friend; the blues singer Mabel John; Stacy Keach as the sheriff, and a newcomer named Gary Clark Jr., who impersonates a famous guitar player booked at Glover’s club. (The movie opens today in Chicago.)

We sat and talked one day. And talked and talked. The transcript came to 8,400 words, and here are some of the things Sayles told me:

“There’s this rock ‘n’ roll legend about a guy named Guitar Slim who was an electric guitar player in New Orleans in the early ’50s. He was known for two things: He had this long extension cord and he would go out on the streets and just lure people like the Pied Piper back into his club with his 300-yard-long extension cord. But he would miss gigs because he partied too much. I’ve heard that Albert King and Albert Collins and B.B. King would have a club owner say, ‘Tonight, you are Guitar Slim.’ Because nobody knew what he looked like; they just heard his stuff on the jukebox.”

“I found the Popular Electronics article where Les Paul describes this new electric guitar that he’s made. So the character that Gary Clark in ‘Honeydripper’ plays is a kid who could have been a radio repairman in the Army and could have read this article, and being a guitar player already, could say, ‘I’m gonna do that.’ He would have played acoustic with a pickup like T-Bone Walker did.”

“We needed an African-American kid who played that kind of stuff, which is rare these days. We were told, ‘You gotta come and see this kid Gary Clark Jr. He’s an Austin kid.’ I think we saw him on the night he turned 21, so his mom no longer had to be the chaperone when he played in clubs that served liquor. He kinda looks like a young Chuck Berry, which was what I had in my head for the character. By the time we shot, he was 22. And he just turned out to be a great kid to work with.”

“We had stars like Danny Glover and Charles S. Dutton, but everybody gets scale and gets paid according to how many days they work. It’s the biggest compliment we get is that we ask these well-known actors to be in our movies, and they say yes for scale. I think the attraction is a) they’re good parts, b) all our movies have gotten at least some kind of theatrical release, because now so many movies get made and not even released theatrically.”

“One of the problems with film schools is so many of the kids coming out of them only know movies. Robert Mitchum was one of the last generation of actors who had a life before he was in movies. You felt it in his performances. Now so many actors and directors, they go right from school. Before they were just watching movies, and then they go right into movies and they have a career right away. I’ve noticed this with Steven Spielberg. He’s growing up. Recently his movies have actually started to deal with stuff out in the real world and not just the movie world. But it took him until he was 50 to feel like he could do that.”

“People call our movies political, but I think of something Haskell Wexler has said a bunch of times: All movies are political. If you see a comedy made in 1935, there are attitudes about race and class and sex that today we would say, wow, what a political statement that’s making! But at the time, it was just the status quo.”

“Honeydripper’ isn’t about race but it’s set in Alabama in 1950 and there are assumptions, because of the apartheid that existed there, that are going to affect people’s lives. You can’t walk down a road as a black man without a job and not end up on the chain gang. That’s gonna create anger and it turns inward, and so always in those juke joints, there was this undercurrent of anger and violence, and it’s in the music. It’s one of the things that Danny Glover’s character has to deal with: One of the reasons people go to these places is to see fights or be in them, and he doesn’t want them in his club. This is his own past, and it’s stupid, senseless violence that’s still with us.”

“This one we’re releasing ourselves, because of the [studio] laziness or the incompetence that’s been so disappointing over the years. We’ve all gotten to be better at making the films but they haven’t gotten any better at distributing. Our independent movies used to get a few weeks to build up word-of-mouth. Now they’re in the same boat as the studio movies; they live or die in the first weekend. And you can’t do that with little movies; they really do need to find their audiences. So either they get lucky like ‘Sideways’ did, or they disappear. The distributors just put it into their system and let it go. They put it in the Landmark chain and it plays one week, and they’re fine; they bought it for probably $100,000 and they get $500,000 back and that’s it.”

I asked Sayles if it changed his life when he won a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant.”

“I’m an ex-genius now. It only lasts five years, and then your IQ drops rapidly. I had never heard of this award. I was in the soundmix for ‘Baby, It’s You,’ and I got this call from somebody who says, ‘You’ve won this award, it’s called the MacArthur Award.’ I was a little annoyed that he called because we only had one week to mix this movie. I figure OK, I gotta go get a trophy. He says, ‘And there’s some money involved.’ I perked up a little. And I said, so, what’s this money? And he says, ‘Well, it’s based on your age,’ and I was 34 at the time, and got $34,000 a year for five years tax-free. I said, that sounds great.”

“Very specifically, we had just made ‘Brother From Another Planet’ on my own nickel, and my nickel had run out, so what it meant was I did not have to go back and write another screenplay, and was able to pay for the editing room, you know, and just go right ahead and finish the movie and not take a hiatus to write. So that was great.”