By Roger Ebert

John Sayles‘ “Honeydripper” is set at the intersection of two movements that would change American life forever: civil rights, and rhythm & blues. They may have more to do with each other than you might think, although that isn’t his point. He’s more concerned with spinning a ground-level human comedy than searching for pie in the sky. His movie is rich with characters and flowing with music.

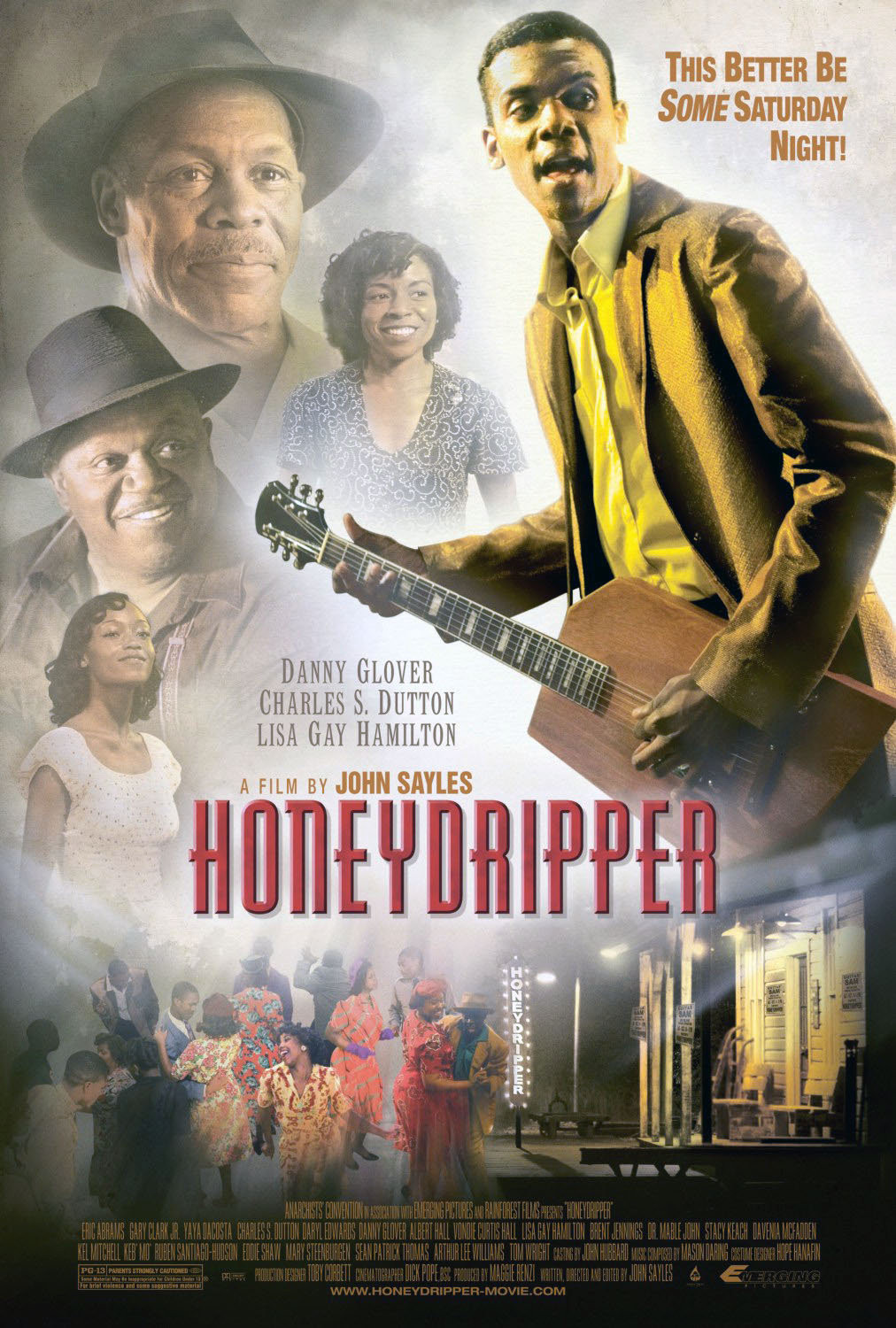

The time, around 1950. The place, Harmony, Alabama. The chief location, the Honeydripper Lounge, which serves a good drink but is feeling the competition from a juke joint down the road. Its proprietor, Pine Top Purvis (Danny Glover), is desperately in debt. The wife, Delilah (Lisa Gay Hamilton), is causing him some concern: Will she get religion and disapprove of his business? His best friend, Maceo (Charles S. Dutton), is a sounding board for his problems. The nightmare is the local sheriff (Stacy Keach), who is a racist, but doesn’t go overboard like most. Club characters: the blues singer (Mable John) and her man (Vondie Curtis-Hall).

Into Harmony one day comes a footloose young man named Sonny, played by Gary Clark Jr., in real life a rising guitar phenom. He drifts into the Honeydripper looking for a job or a meal, and carrying something no one has ever seen before: a homemade electric guitar, carved out of a solid block of wood. Pine Top has no work for him, and the youth is soon arrested by the sheriff (his crime: existing while unemployed) and put to work picking cotton for a crony.

Meanwhile, in desperation, Pine Top books the great Guitar Sam out of New Orleans and puts up posters all over town. Sure, he can’t afford him, but the plan is, Guitar Sam will bring in enough business on one Saturday night to pay his own salary and also the lounge’s worst bills. Pine Top finds out what real desperation is when Guitar Sam doesn’t arrive on the train. He wonders if the kid with the funny guitar can play a little. After all, no one in Harmony knows what Guitar Sam really looks like.

Now all the pieces are in place for an unwinding of local race issues, personal issues, financial issues and some very, very good music, poised just at that point when the blues were turning into rhythm and blues, which after all is what rock ‘n’ roll is only an alias for. Because after all, yes, the kid can play a little. More than a little.

John Sayles has made 19 films, and none of them are two-character studies. As the writer of his own work, he instinctively embraces the communities in which they take place. He’s never met a man who was an island. Everyone connects, and when that includes black and white, rich and poor, young and old, there are lessons to be learned, and his generosity to his characters overflows into affection.

Danny Glover is well cast to stand at the center of this story. A tall, imposing, grave presence as Pine Top, he is not so much a music lover as a survivor. This is his last chance to save the Honeydripper and his means of making a living. And Gary Clark Jr. is the right man to be told: “Tonight, you are Guitar Sam.” He may be a prodigy, but he is broke, scared, young and far from home. So this isn’t one of those show-biz stories where a talent scout is in the audience, but a story where the audience looks at him with great suspicion until his music makes them smile.

As for the sheriff’s role: As I suggested, lots of Alabama sheriffs were more racist than he is, which is not a character recommendation, but means that he isn’t evil just to pass the time and would rather avoid trouble than work up a sweat. At that time, in that place, he was about the best you could hope for. Within a few more years, the Bull Connors would be run out of town, one man would have one vote, and the music of the African-American South would rule the world. That all had to start somewhere. It didn’t start on Saturday night at the Honeydripper, but it didn’t stop there, either.