“I don’t think Capote knew exactly what he was setting himself up for,” Philip Seymour Hoffman said. “He said later if he’d known what was going to happen, he would have driven right through the town like a bat out of hell.”

But he didn’t. Truman Capote stayed in Holcomb, Kan., and returned on and off over the next six years, writing In Cold Blood, a great book, which after 40 years is still read and valued, but which destroyed its author. The book inspired a movie at the time, about the murder of the Clutter family, and now it has inspired another, about the triumph and self-destruction of Truman Capote.

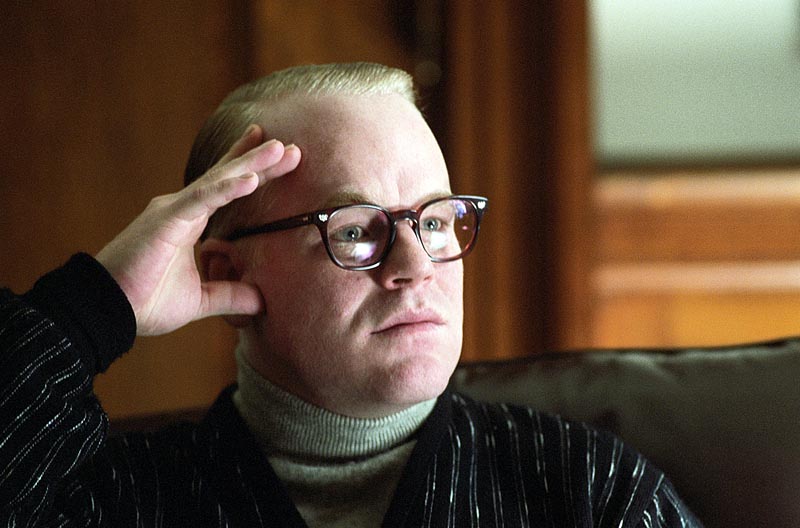

Hoffman looks very much like himself and not particularly like Capote, but in “Capote,” he has the inner music right, and he feels like Capote, like the small, precise gay man with the affectations and eccentricities who walked into the middle of America and brought back a portrait of ordinary people visited by tragedy. If there is such a thing as a lock on an Oscar nomination, Hoffman has one; in a year rich in performances, his is remarkable.

Hoffman will never be confused with a matinee idol, but by taking chances with good directors and unconventional projects, he has become one of the most interesting actors of his generation: Consider such films as “Boogie Nights,” “The Big Lebowski,” “Happiness,” “Magnolia,” “Almost Famous,” “State and Main” (2000), “Punch-Drunk Love,” “Flawless” and “Owning Mahowny.” Consider the directors Paul Thomas Anderson, Todd Solondz, David Mamet, Cameron Crowe, Joel Schumacher and the Coen brothers. This is a career.

Bennett Miller, who directed “Capote,” is not only Hoffman’s director, but his old friend: “I met Bennett and Danny Futterman, who wrote the screenplay, when we were all 16 years old and in this summer theater program — and there we were on my porch in Manhattan when we’re 35, talking about making this film, and two years later, we made it.”

Hoffman and Miller were visiting Chicago to promote their film, which opens here Friday. I asked Miller how this actor he had known for 20 years became a character so completely unlike himself.

“One aspect is the mechanical aspect,” Miller said, so softly he could have been talking to himself. The two men are opposites, Hoffman verbal and outgoing, Miller viewing the world with grave misgivings. “His performance begins with and depends on the voice. How Philip does Capote physically, that’s something an actor does alone in a room with the door locked. He worked on it for five and a half months. We gave him audio and video tapes, and it was a matter of methodical rehearsal. He’s not a mimic by nature. But the deeper aspects of Capote are a little more mysterious, and how Phil managed to tune into that frequency transcends the mechanical work that he did.”

Hoffman himself seems a little surprised by the uncanny way his performance resonates.

“An acting teacher of mine once said about Sissy Spacek in ‘Coal Miner’s Daughter’ that she was more Loretta Lynn than Loretta Lynn was. Spacek could capture a truth and essence that Loretta Lynn could never do because she was Loretta Lynn. Spacek could be objective, the way I can be objective about Capote and find the truth about what possibly made him tick.

“I wasn’t concentrating on how to mimic him,” he said. “I was concentrating on what put him into action. I got away from worrying about doing him exactly. I knew I had to get close to the voice and the mannerisms, but at the end of the day, if I didn’t understand what drove him that none of that stuff would have been any good.”

He does understand. He portrays Capote as a man who finds himself the captive of an overwhelming opportunity. He goes to Kansas thinking he will write about how a town deals with tragedy, and then he meets the two men arrested for the murders, Dick Hickock and Perry Smith, and he becomes their confidant. He sees the human beings inside the monsters. He falls in love with Smith. But he has a greater love for his book, which he correctly senses will be big and important. And in the end, he betrays Smith. He pretends to work on their behalf for an appeal, but he needs for the men to die so that his book can have an ending.

“It was an inevitable tragedy,” Hoffman said. “He was unaware that it was happening until it was too late. He wanted to write this great book that would bring him more acclaim and love than ever before, but this other thing was just as powerful, this intimacy that was created, especially with Perry. He said later on he became closer with those two than he was with anyone else in his life.

“If you have that kind of intimacy alongside ambition, ultimately it’s going to leave an incredibly tragic impression on his psyche and spirit. He paid a huge price to write one of the great books of the 20th century. Capote didn’t go to Kansas. Kansas reached out to New York and grabbed Capote. The minute he met Perry Smith, it was inevitable that these two men were going to die, one literally and one figuratively, because the identification they shared was too deep. The minute he got Perry to open up about his own life, and he learned they were both orphans, they were both abandoned children, he sees his muse, and that’s the beginning of the end. Kansas sprung a trap on him.”

Although Capote was an exotic original, Hoffman often plays characters who are so ordinary, they seem to be making a point of it. In “Owning Mahowny” (2003), he plays a Toronto bank officer who embezzles millions and loses it all in Atlantic City and Las Vegas, and seems to be in a trance when he’s at the tables. At one point, he takes his girlfriend to Vegas and forgets she’s there. Mahowny could get overlooked in a one-man lineup, and yet I will never forget the character. How does that happen?

“Acting is just hard for me,” he said. “As I’ve gotten older I’ve gained a certain facility, but ultimately I know that if I don’t feel for the material in a way that keeps me up at night, it’s gonna be harder for me to act well. It might not ultimately be a great movie but hopefully, it will be a movie that somebody is gonna find interesting. It’s not that I haven’t made decisions based on money in my life. I definitely have and will again, but I try to keep those as far apart as possible. And even when I make those decisions, I still want to find something in the material that will get me active in finding out how I can act this thing well. Because if I’m left to my own devices, it’s real empty in here.”

He chooses directors, he said, because he likes their other work. “The way Bennett is and the way Cameron Crowe is and the Coen brothers, Paul Thomas Anderson — those are the guys you wanna work with. They’re like children; they have the energy and excitement a child has, and that’s necessary. Because if you’ve got somebody like me who’s incredibly self-critical and can get down, you need an energy that is constantly reviving the atmosphere.”

Hoffman admits he’s heard the talk about Oscars, and he doesn’t beat around the bush: “I’m very excited people are talking like that. I usually hide my feelings about things like the Oscars. But I believe in the film. Hell or high water, here we are, and people are actually going to see it, a lot more than we thought would, and they’re responding the same way we felt about it. So I’m excited and I hope the film is still in theaters six months from now, and the Oscar buzz is only gonna help. I don’t want it to go away. I want it to be in the theaters in May.”

Related story by Roger Ebert:

Truman and Lee and the Prince: An Opening Night (1967)

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

CAPOTE FOR DUMMIES:

“Life is a moderately good play with a badly written third act.”

That sums up the sardonic wit of Truman Capote, who, despite his short stature, high-pitched lisp and generally outre style, made an outsized impact on pop culture. Among some entries on his curriculum vitae:

Biographical

Born Sept. 30, 1924, as Truman Streckfus Persons in New Orleans, he later took his stepfather’s surname and reinvented himself as Truman Garcia Capote.

Gave his height as 5’3″ — “as tall as a shotgun, and just as noisy” — though many thought he was much shorter.

Relationships

Fellow Southern literary lion Tennessee Williams is a distant relation, his seventh cousin once removed.

His aunt who helped raise him as a child is Marie Rudisill, a.k.a. “The Fruitcake Lady” (1992-2000) from “The Tonight Show” with Jay Leno.

His childhood friend Harper Lee used Capote as the basis for Dill in her novel To Kill a Mockingbird.

Openly gay when it was scandalous to be so; his longtime partner Jack Dunphy chronicled their time together in Dear Genius: A Memoir of My Life With Truman Capote (1987).

Important works

His most famous is In Cold Blood (1965), which he called “a non-fiction novel”; along with Gay Talese and Tom Wolfe, Capote created a new literary style that changed the world of journalism and storytelling.

His first novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948); the novellas The Grass Harp (1951) and Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958); the short story A Christmas Memory (1966).

Milestones

Billed as “The Party of the Century,” his Black and White Ball in 1966 at New York’s famed Plaza Hotel drew the glitterati from the literary, society, cinematic and political worlds. Recalled columnist Aileen (“Suzy”) Mehle: “There was a wonderful, hectic gaiety about the whole party. Truman would hop, skip and jump from table to table and say, “Aren’t we having the most wonderful time?”

Later, his jet-set friends, which he skewered in Answered Prayers (previewed in Esquire magazine in 1975), turned against him, triggering his personal and professional decline.

Quirks

Did not like to take notes or tape interviews, instead preferring to rely on his near-photographic memory; in his reporting for In Cold Blood, he claimed to have “94 percent recall.”

Quips

One of his most famous lines was his dismissal of Jack Kerouac’s beat novel On the Road: “That’s not writing, it’s typing.”

Movies

With director John Huston, he co-wrote the script for the offbeat comedy “Beat the Devil” (1954). He also co-wrote the screenplay for “The Innocents” (1961), an adaptation of Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw.

He appeared as Lionel Twain (“IT! IT is confusing! Say your goddamn pronouns!”) in Neil Simon’s film comedy “Murder by Death” (1976), for which he received a Golden Globe nomination as best new male star.

In “Annie Hall” (1978), he turns up as a “Truman Capote look-alike.”

Death

Felled by a drug overdose Aug. 25, 1984, at age 59, in the home of Joanne Carson, former wife of “The Tonight Show” king.

Rests in a mausoleum in L.A.’s Westwood Village Memorial Park, next to Heather O’Rourke (“Poltergeist“) and Mel Torme (“The Velvet Fog”).

Compiled by Laura Emerick

Sources: imdb.com, Wikipedia.com, capotebio.com and questia.com

Related stories: