“If the Sixties and early Seventies were, at least in part, periods of disillusionment, the late Seventies and Eighties brought a process of re-illusionment. Its agent was Ronald Reagan. His mandate wasn’t simply to restore America’s economy and sense of military superiority but also, even more crucially, its innocence.” – J. Hoberman, Make My Day

In September 1980, the eve of the first term election of Ronald Reagan, J. Hoberman published, in the Village Voice, a jaundiced critique of the former actor. “Reagan made a successful career out of establishing the ‘likeability’ of his two-dimensional image,” Hoberman began. “He spent three decades practicing a form of hoodoo—the Dr. Strange-like projection of his ectoplasmic form—over radio, in the movies, and on TV. The package may be shopworn, but the historian must stand in awe of its prophetic vision.”

Few American film critics have rivaled Hoberman in his range, versatility and expertise. As a critic at the Voice, his acute and remarkable insights touched all sides, encompassing though hardly limited to the American experimental and underground cinema, Bruce Lee and blaxploitation titles, French New Wave and most significantly, the furtive history of Jewish and Eastern European cinema.

The Reagan era was Hoberman’s true metier. As Hollywood colonized the world, perfecting the blockbuster and monopolizing markets, Hoberman dissected their deeper meanings and political implications through the key works of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas. Robert Zemeckis’ “Who Framed Roger Rabbit,” for instance, suggests “the last efflorescence of Spielbergism—that is, the process by which the subversively self-reflexive practice of the French New Wave was recuperated in the service of building bigger, better, and blander entertainment machines.”

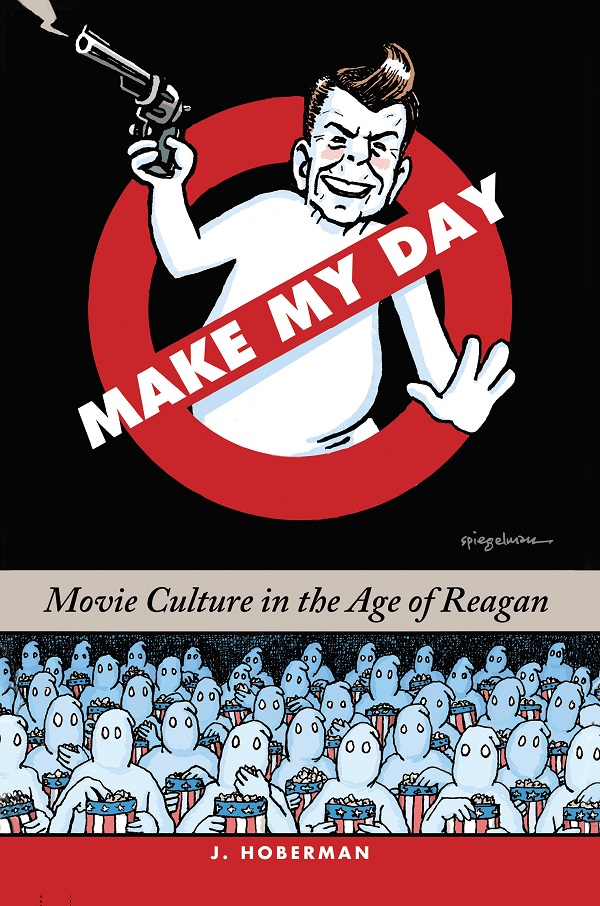

The movies, the politics, the Reagan persona, are the subject of Hoberman’s enthralling new cultural history, Make My Day, the concluding work of a trilogy that began with The Dream Life, about the 1960s, and continued with An Army of Phantoms, about film noir, the Cold War and the blacklist.

The new book, Hoberman writes in the introduction, “is not a work of film criticism. Nor is it strictly speaking a history. I see it rather as a chronicle in which political events and Hollywood movies are folded into each other to illuminate what, writing in 1960, [Norman] Mailer termed America’s ‘dream life.’ Consequently I have discussed many movies that I dislike, often at some length, and omitted or minimized some that I admire.”

The view is typically kaleidoscopic, limited not just to Reagan’s years as president though his emergence as a political force. It begins with Lucas’ “American Graffiti” and a fascinating interplay of Spielberg’s “Jaws” and Robert Altman’s “Nashville” and ends with John Carpenter’s bleak and corrosive “They Live.” During a recent phone interview from his home in New York, J. Hoberman talked about Reagan, movies and the dream life.

This feels like a culminating text for you, a book that you have been destined to write. Both Vulgar Modernism and The Dream Life, conclude with chapters about Reagan.

That’s true. I don’t know if I was destined to write it, but I felt like I had to. It was really the culmination of two previous books, “The Dream Life” and “Army of Phantoms.”

You allude to Arthur Kroker’s quotation of society as a mirror of television. Reagan also inverted the normal dynamic so that the invasion of Grenada is the equivalent of his Rambo, his policies recast revisionist fantasy.

Reagan was so immersed in the Hollywood worldview or the imperatives of Hollywood entertainment that he could project these scenarios out into the world. He did a great job with it. I don’t think Grenada is remembered today, but it was a huge hit then.

You talk about, in movies like “Back to the Future” or “Blue Velvet,” about the superimposition of the Fifties over the Eighties. For all the cultural conformity of the Eisenhower period, we had great directors like Samuel Fuller, Nicholas Ray and Robert Aldrich who were saying far more damning things about the culture and country, Fuller especially in taking on American racism.

That’s a very good point. When I refer to the Fifties, I mean the imaginary Fifties, “Happy Days.” The actual Fifties, especially in the first half, were very different, very anxious and scary. Regan didn’t create nostalgia for an imaginary Fifties. It already existed. “American Graffiti” put that into play. He did promote an imaginary past and that is the Fifties that is superimposed over the Eighties.

Speaking of Fuller, Reagan was really damaging to film culture because his ideology pervaded industry practices. As Jonathan Rosenbaum pointed out, ownership superseded authorship, and it had terrible consequences, I am thinking of the example of Paramount with “White Dog,” or Warner Brothers on the original cuts of “Once Upon a Time in America” or “Swing Shift.”

By his very existence, Reagan promoted a kind of old-fashioned view of Hollywood. The studios lost a lot of power in the Fifties, and that created opportunities for somebody like Sam Fuller, and in general for other genre director with social interests like Robert Aldrich and Don Siegel, in some ways. In the Sixties, the system itself began to fall apart and that was really great for movies. In the latter half of the Sixties into the first part of the Seventies, you had an American New Wave, where confusion reigned and authorship challenged ownership.

There was a tremendous reaction to that. “Jaws” is the handy culprit and also “Star Wars,” but those are very much author films, so there’s a paradox. As Reagan reorganized American politics so Hollywood reorganized itself, having discovered the significance of the blockbuster, and what would later be called convergence culture. All movies would aspire to not only being tremendous hits on their first weekends, but to spin off sequels and all sorts of ancillary merchandise.

I think it’s one of the great achievements of the book to expose the fallacy of the Hollywood liberal orthodoxy. Reagan movies are not just reactionary, but protecting and preserving of the status quo.

That is true of entertainment in general and certainly of Hollywood, except for a very few periods. One was the Sixties, when the industry was in crisis, and you have all of these movies that are pessimistic, disruptive or subversive. The only other period is the Depression before the Production Code, although you could also say the whole film noir tendency that starts during World War II and continues into the Cold War is also oppositional. It’s certainly pessimistic. It goes against the enforced optimism of Hollywood. By the Eighties, you can’t have a movie that doesn’t just have a happy ending, but an insanely affirmative ending. “Rocky” becomes the template for what a Hollywood movie should be.

I never realized until reading the book you were at Berkeley during Reagan’s first term as governor of California.

I was there in the summer of 1968 and again during the summer of 1969.

How much did that experience shape your feelings and attitudes about him?

Completely. I disliked him, but after 1968 I really hated him. Before I didn’t have any sense of him, or who he was. I don’t think I ever saw him in the movies.

Not even “The Killers.”

I saw “The Killers” after I was in Berkeley. The whole experience was eye-opening. As governor Reagan had targeted students, longhairs, people like me who were rioting every night on Telegraph Avenue. It was quite something. You could not but be swept up in them—it seemed like a life and death thing. I loathed Reagan. He was horrible. In June 1969, I saw “The Killers,” and I wasn’t expecting to see Reagan. I went to see it because it was a Don Siegel film, at the Museum of Modern Art. It was a revelation. To me, it didn’t even seem like he was acting. I thought he was somehow playing himself—a very naive response to the movie.

Still, forever after, even when he developed this other persona after being president of being this chuckling, avuncular and kindly old guy who people loved I would think, to quote a movie, “you may be a one-eyed Jack in this town but I’ve seen the other side of your face.” The real Reagan was in “The Killers.”

Dave Kehr is another critic you allude to a lot in the book, and he made a great point about the defining characteristic of Reagan era films in his capsule of “Top Gun,” the suppression of individuality in order to become a team player.

Actually “Top Gun” promotes a kind Uber individualism. There can only be one “Top Gun.” Even though he is a member of the team, a supporter of the status quo, he is No. 1. That is something that was promoted throughout the Reagan period. Rambo wins the Vietnam War. Arnold rules. Reagan himself would be the exemplar of that.

It’s interesting as well to track the different stylistic and thematic ideas that you pursue throughout the trilogy, but also your other work. “Eraserhead” is probably the key film in Midnight Movies, and “Blue Velvet” probably the defining work of this book.

There are certainly a handful of movies that were produced in Hollywood or close to Hollywood that to me are great films. “The King of Comedy” is one, so is “Videodrome,” even though it was made outside Hollywood. “Ishtar” looks better and better. There are some other movies that I see as being Eighties movies being turned inside out. “Gremlins” would be an example of that, and also “Aliens” and “RoboCop.” There aren’t all that many.

Make My Day doesn’t deal with independent films, that was something that was going outside the margins. I wrote about them in the Voice, but they’re not the subject of this book.

The three books reflect so much of your sensibility and what has driven you, as a critic, writer, historian and teacher, the last four decades. I was curious, with this book or any of the books, do you struggle sometimes in reconciling how much of yourself to put into them.

I definitely did with Make My Day. It was the hardest for me to write. All of them are different. For Army of Phantoms, I did a tremendous amount of research, and I was learning things all the time. It was very exciting. The Dream Life was pure pleasure, enabling me to revisit my youth (I was born in 1949) and think about it.

However, I lived through Reagan as an adult, not just an adult a professional film critic. I saw all of these movies including many I didn’t much care for. It’s not like my opinion of these movies (or Reagan for that matter) changed while I was working on the book. In the other books, I relied quite a bit on contemporary film criticism to examine what people were saying about the movies. I had the advantage to check how things were reviewed in the Daily Worker in the Forties and Fifties, and the underground press in the Sixties. In the Eighties, those publications barely existed but I was writing. So I used certain of my own pieces of writing that I felt held up and were symptomatic of the times.

I quote plenty of other people too. I was always looking for critics like Richard Grenier or John Podhoretz who were ideological. But because I added my own voice, Make My Day is more personal than the earlier books.

We have seen the disruptive and devastating repercussions of technology, demographics and market forces with media, the alternative weeklies and now foreign language and specialized cinema, I was curious how you think your own work has been changed by the internet.

In some ways, the internet put me out of a job. I got laid off from the Voice because they were retrenching. There were other reasons too. I was very active in the union, part of the struggle against the way the paper was being downsized. So I am no longer a regular film critic although I continue to write on movies. Initially I thought I would never write just for online publication. That lasted about a month. I quickly learned that by and large online was what there was. A lot of what I write now is just online. It never seems as significant to me as something in print but that is my nostalgia. The internet happened, and it gives and it takes away.

When I started reading you in the Eighties, I always marveled at the contextual layering of your reviews. Even in the analog era, you seemed to have an astonishing recall for facts at your command.

Well, History and English were my two favorite subjects at school. I had a natural curiosity about things that happened in the past and a good memory for that stuff. As I think back on the other books that I have done, Bridge of Light, the book I wrote on Yiddish films really is a history, that is a history using film as its subject. Probably that method affected my subsequent work. For that matter, Midnight Movies was a book that was about a historical period. Writing about the cults films of the Seventies, Jonathan [Rosenbaum] and I were aware of the historical baggage they carried.

Exactly, Ben Barenholtz, who just passed away, I was aware of him, but until reading Midnight Movies, I had no idea of how crucial a figure he was in the New American Cinema.

We spent a lot of time talking to him. Shortly thereafter, he discovered Guy Maddin and also the Coen Brothers. His career was in an upward arc but his prior promotion of “El Topo” and “Pink Flamingos” and “Eraserhead,” really makes him in some respects the central figure of that whole midnight movie tendency.

Perhaps the fitting irony is that Reagan’s two terms as president were more or less bookended by “Heaven’s Gate and “Ishtar,” two films ridiculed for their overreach, hubris and the financial damage they caused. “Heaven’s Gate” now has the imprimatur of Criterion boxed set. As you pointed out recently in The New York Times, the critical thinking about “Ishtar” is also much more appreciative. Their reputations have eclipsed Reagan’s.

Among some people. The book’s last chapter, I draw attention to the fact that when Reagan left office he was regarded as a good guy but hardly a great president—let alone the greatest president since Lincoln, which seems to be an article of faith in the Republican Party. So we have to deal with that part of the Reagan movie also—his imaginary, posthumous political career.