My first car was a ‘54 Ford and I bought it for $435. It wasn’t scooped, channeled, shaved, decked, pinstriped, or chopped, and it didn’t have duals, but its hubcaps were a wonder to behold.

On weekends my friends and I drove around downtown Urbana — past the Princess Theater, past the courthouse — sometimes stopping for a dance at the youth center or a hamburger at the Steak ‘n’ Shake (“In Sight, It Must Be Right”). And always we listened to Dick Biondi on WLS. Only two years earlier, WLS had been the Prairie Farmer Station; now it was the voice of rock all over the Midwest.

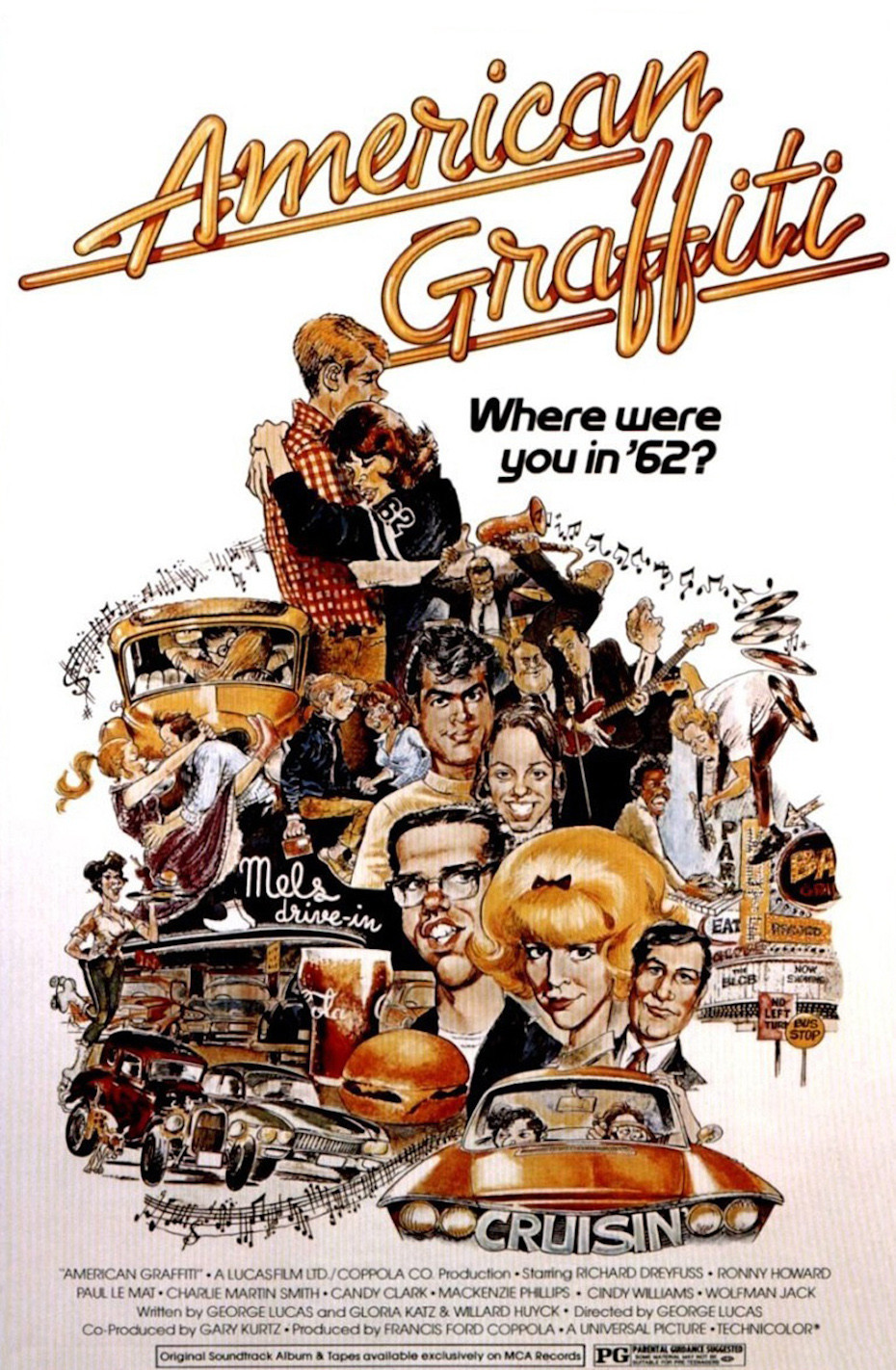

When I went to see George Lucas’s “American Graffiti” that whole world — a world that now seems incomparably distant and innocent — was brought back with a rush of feeling that wasn’t so much nostalgia as culture shock. Remembering my high school generation, I can only wonder at how unprepared we were for the loss of innocence that took place in America with the series of hammer blows beginning with the assassination of President Kennedy.

The great divide was November 22, 1963,and nothing was ever the same again. The teenagers in “American Graffiti” are, in a sense, like that cartoon character in the magazine ads: the one who gives the name of his insurance company, unaware that an avalanche is about to land on him. The options seemed so simple then: to go to college, or to stay home and look for a job and cruise Main Street and make the scene.

The options were simple, and so was the music that formed so much of the way we saw ourselves. “American Graffiti”‘s sound track is papered from one end to the other with Wolfman Jack’s nonstop disc jockey show, that’s crucial and absolutely right. The radio was on every waking moment. A character in the movie only realizes his car, parked nearby, has been stolen when he hears the music stop: He didn’t hear the car being driven away.

The music was as innocent as the time. Songs like “Sixteen Candles” and “Gonna Find Her” and “The Book of Love” sound touchingly naive today; nothing prepared us for the decadence and the aggression of rock only a handful of years later. The Rolling Stones of 1972 would have blown WLS off the air in 1962.

“American Graffiti” acts almost as a milestone to show us how far (and in many cases how tragically) we have come. Stanley Kauffmann, who liked it, complained in the New Republic that Lucas had made a film more fascinating to the generation now between thirty and forty than it could be for other generations, older or younger.

But it isn’t the age of the characters that matters; it’s the time they inhabited. Whole cultures and societies have passed since 1962. “American Graffiti” is not only a great movie but a brilliant work of historical fiction; no sociological treatise could duplicate the movie’s success in remembering exactly how it was to be alive at that cultural instant.

On the surface, Lucas has made a film that seems almost artless; his teenagers cruise Main Street and stop at Mel’s Drive-In and listen to Wolfman Jack on the radio and neck and lay rubber and almost convince themselves their moment will last forever. But the film’s buried structure shows an innocence in the process of being lost, and as its symbol Lucas provides the elusive blonde in the white Thunderbird — the vision of beauty always glimpsed at the next intersection, the end of the next street.

Who is she? And did she really whisper “I love you” at the last traffic signal? In “8 1/2,” Fellini used Claudia Cardinale as his mysterious angel in white, and the image remains one of his best; but George Lucas knows that for one brief afternoon of American history angels drove Thunderbirds and could possibly be found at Mel’s Drive-In tonight… or maybe tomorrow night, or the night after.