John Waters‘ “Pink Flamingos” has been restored for its 25th anniversary revival, and with any luck at all that means I won’t have to see it again for another 25 years. If I haven’t retired by then, I will.

How do you review a movie like this? I am reminded of an interview I once did with a man who ran a carnival sideshow. His star was a geek, who bit off the heads of live chickens and drank their blood.

“He’s the best geek in the business,” this man assured me.

“What is the difference between a good geek and a bad geek?” I asked.

“You wanna examine the chickens?” “Pink Flamingos” was filmed with genuine geeks, and that is the appeal of the film, to those who find it appealing: What seems to happen in the movie really does happen. That is its redeeming quality, you might say. If the events in this film were only simulated, it would merely be depraved and disgusting.

But since they are actually performed by real people, the film gains a weird kind of documentary stature. There is a temptation to praise the film, however grudgingly, just to show you have a strong enough stomach to take it. It is a temptation I can resist.

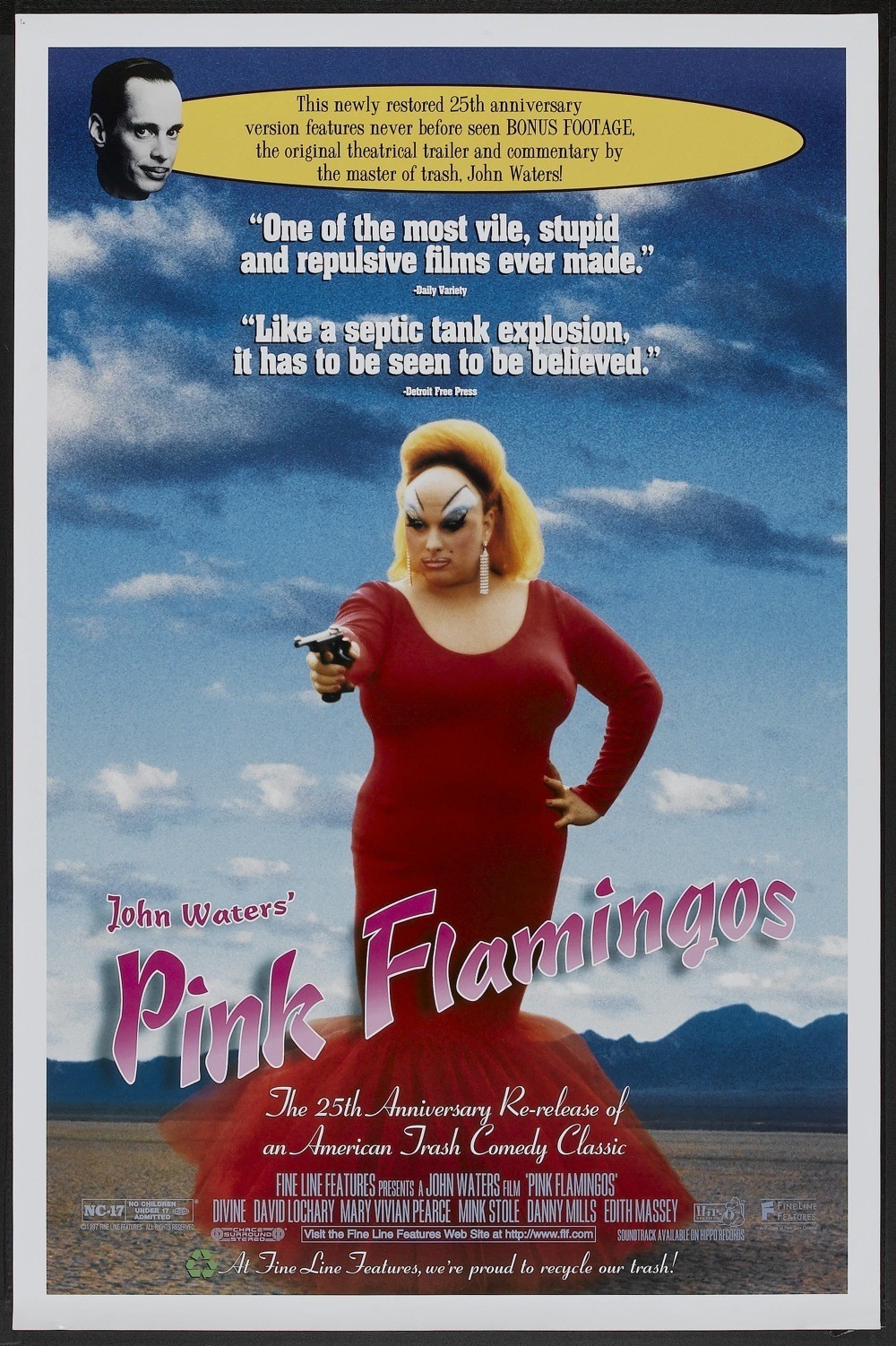

The plot involves a rivalry between two competing factions for the title of Filthiest People Alive. In one corner: A transvestite named Divine (who dresses like a combination of showgirl, dominatrix and Bozo); her mentally-ill mother (sits in a crib eating eggs and making messes); her son (likes to involve chickens in his sex life with strange women); and her lover (likes to watch son with strange women and chickens). In the other corner: Mr. and Mrs. Marble, who kidnap hippies, chain them in a dungeon, and force their butler to impregnate them so that after they die in childbirth their babies can be sold to lesbian couples.

All the details of these events are shown in the film, including the notorious scene in which Divine actually ingests that least appetizing residue of the canine. And not only do we see genitalia in this movie–they do exercises.

“Pink Flamingos” appeals to that part of our psyches in which we are horny teenagers at the county fair with fresh dollar bills in our pockets, and a desire to see the geek show with a bunch of buddies, so that we can brag about it at school on Monday. (And also because of an intriguing rumor that the Bearded Lady proves she is bearded all over.) After the restored version of the film has played, director John Waters hosts and narrates a series of out-takes, which (not surprisingly) are not as disgusting as what stayed in the film. We see scenes in which Divine cooks the chicken that starred in an earlier scene; Divine receives the ears of Cookie, the character who co-starred in the scene with her son and the chicken; and Divine, Cotton and her son sing “We Are the Filthiest People Alive” in Pig Latin.

John Waters is a charming man, whose later films, such as “Polyester” and “Hairspray” (1988), take advantage of his bemused take on pop culture. His early films, made on infinitesimal budgets and starring his friends, used shock as a way to attract audiences, and that is understandable. He jump-started his career, and in the movie business, you do what you gotta do. Waters’ talent has grown; in this film, which he photographed, the visual style resembles a home movie, right down to the overuse of the zoom lens. (Amusingly, his zooms reveal he knows how long the characters will speak; he zooms in, stays, and then starts zooming out before speech ends, so he can pan to another character and zoom in again.) After the out-takes, Waters shows the original trailer for the film, in which, not amazingly, not a single scene from the movie is shown. Instead, the trailer features interviews with people who have just seen “Pink Flamingos,” and are a little dazed by the experience. The trailer cleverly positions the film as an event: Hey, you may like the movie or hate it, but at least you’ll be able to say you saw it! Then blurbs flash on the screen, including one comparing “Pink Flamingos” to Luis Bunuel’s “The Andalusian Dog,” in which a pig’s eyeball was sliced. Yes, but the pig was dead, while the audience for this movie is still alive.

Note: I am not giving a star rating to “Pink Flamingos,” because stars simply seem not to apply. It should be considered not as a film but as a fact, or perhaps as an object.