October, 1971; the Back to School issue. That was my first exposure to the National Lampoon. I was in high school, had recently discovered the Marx Brothers, and had the vague feeling I had outgrown Mad Magazine, which was confirmed when I read in that very issue of the Lampoon, a Mad parody (“What, Me Funny?”) which contained the feature, “You Know You’ve REALLY OUTGROWN MAD When… ” (“You find a richer source of humor in everyday things…like rocks”). I was ready for it.

And I’ve been waiting for “Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead: The Story of the National Lampoon,” a new documentary by Douglas Tirola that for the first time onscreen chronicles a comedy revolution—albeit short-lived—that paved the way for “Saturday Night Live,” The Onion, “The Daily Show” and its offshoots, “Politically Incorrect” and “Real Time with Bill Maher,” among many others.

If, as they say in “Bad Day at Black Rock,” that a man is only as big as what makes him mad, then the Lampoon staffers were giants, peeking into society’s darkest corners to mock politics, sex, racism, corruption, war and conformity in ways that I had never dreamed or dared to laugh at.

The National Lampoon was an offshoot of The Harvard Lampoon. Published between 1970 and 1998, the magazine was in its earliest years a comedy Camelot in which some of the best comic minds of their generation gathered together for the express purpose of going too far with such pieces as “The Vietnamese Baby Book,” “The Nazi Dr. Doolittle” (he made the animals talk), and the elegantly titled, “How to Drive Fast on Drugs While Getting Your Wing-Wang Squeezed and Not Spill Your Drink.”

The January 1973 issue featured the magazine’s defining cover image of a nervous looking canine with a gun pointed at its head and the headline, “Buy This Magazine or We’ll Kill This Dog.”

Its violation of comedy’s Rule of Three aside, the title “Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead” brilliantly encapsulates the mondo, snakes-on-everything attitude of the Lampoon’s first two decades. The film shares its title (by permission) with a coffeetable book by artist and Lampoon contributor Rick Meyerowitz, who created the magazine’s signature visual, Mona Gorilla, as well as the iconic poster for the Lampoon’s inaugural foray into feature films, “National Lampoon’s Animal House.”

That poster was Tirola’s entry into the Lampoon universe. Tirola, 48, turned 12 when the film was released in 1978. “I begged my parents to see that movie,” he said in a phone interview. “My dad, who was in a fraternity in college, and I went opening night. We went to the 7pm show and then got back in line for the 9:30 show. That’s the only time I’ve ever done that.”

He sought out the magazine in baseball card shops and in the collections of his friends’ older brothers. He purchased “The National Lampoon’s Tenth Anniversary Anthology: 1970-1980.” “It came with me to college, to my first apartment in New York, to L.A. and back to New York,” he said.

During this time, Triola became a filmmaker. While pursuing a Masters in writing at Columbia University in New York, he, on a whim, finagled a job working on the set of “When Harry Met Sally…” “That’s where I got the bug,” he shared.

Tirola worked on a succession of films, including “A League of Their Own” and “Prelude to a Kiss,” rising through the ranks as a production assistant, production coordinator and location manager.

He made his directorial debut with the indie “A Reason to Believe” and for a time lived in Hollywood, writing screenplays and doing rewrites. None got produced, he said, “but I made a nice living.” Back to New York, where he started his own production company, 4th Row Films, which produced Robert Greene’s well-received documentary “Actress,” and Tirola’s “Hey Bartender” and “All In: The Poker Movie,” an award-winner on the film festival circuit.

Tirola considered doing a documentary about the National Lampoon, but had heard a rumor that Oscar-winning documentarian Barbara Kopple had been approached. (He’s right; I called Cabin Creek Films, her production company, and they confirmed it). And that was that, he figured.

But then came the dinner-party incident. During the depths of the economic meltdown in 2009, Tirola attended a dinner party with his wife in Westport, CT, home to many Wall Street types. As Tirola tells it, someone at the party was dismissive and condescending, which is when Tirola said something to the effect that the Wall Street guy had no values. Tirola compared him to a prostitute in Europe during World War II, and that Tirola had more sympathy for the prostitute.

Next thing you know, “the hostess is crying and another party guest is offering to drive my (embarrassed) wife home,” he said. “It was the worst night of my marriage.”

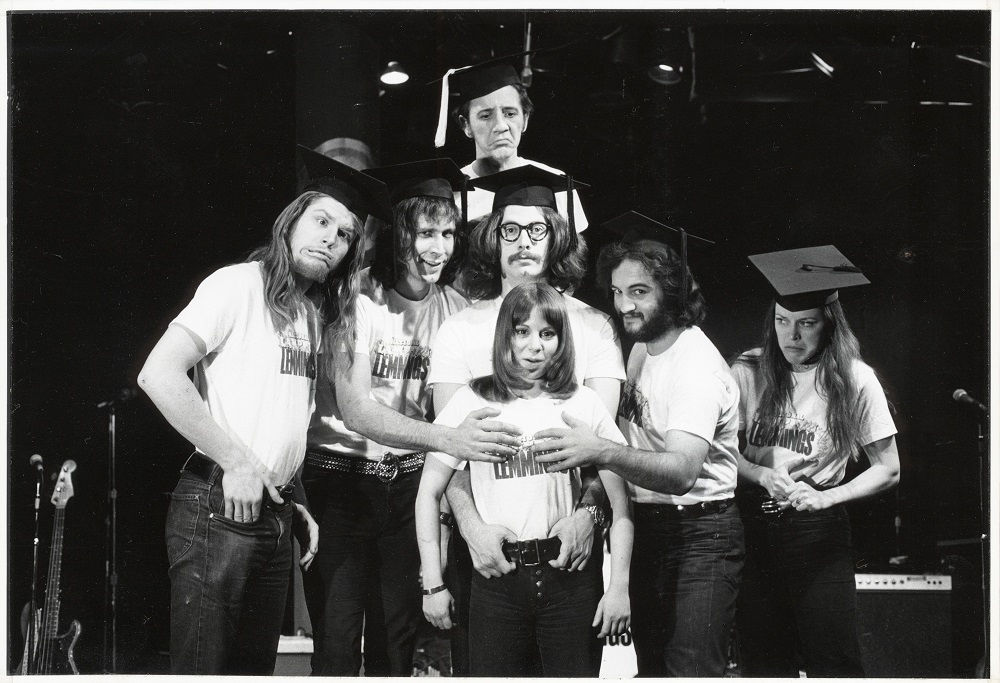

But a friend’s comment—“You always go too far”—stuck with him. He reflected on the National Lampoon and its influence on him. Inspired anew, he approached National Lampoon, Inc. to pitch them on a documentary that would focus on the magazine’s peak creative years and the expansion of the brand into stage shows (“Lemmings”), albums (“Radio Dinner”), radio (The National Lampoon Radio Hour, which featured Christopher Guest, Chevy Chase, and former Second City ensemble members Harold Ramis, Gilda Radner, Bill and Brian Doyle-Murray and John Belushi), and feature films.

To Matty Simmons, the magazine’s former honcho, Tirola pitched a long overdue tribute to “a very special moment in time” and this particular group of writers and artists whom Tirola compared to the expatriates in Paris, the Algonquin Roundtable wits, and the Beat Generation scribes. Simmons gave his blessing.

Complicating matters was that corporate did not have a current relationship with any of the people Tirola wanted to interview; names that may not be popularly known, but who among comedy geeks rank in the pantheon: Chris Miller, whose yarns from his days at Dartmouth inspired “Animal House,” P.J. O’Rourke, Anne Beatts, Mike Reiss and Al Jean, future writers and showrunners on “The Simpsons”, Ed Subitzky, and the film’s major coup, Henry Beard, who co-founded the magazine with Doug Kenney (co-creator of the benchmark “The 1964 High School Yearbook Parody”) and Robert Hoffman, and who had not granted an interview in decades (he is also featured in Mike Sacks’ essential collection of interviews with comedy writers, “Poking a Dead Frog”)

“It became a process of convincing them to be in the movie,” Tirola said. “It wasn’t like any of them were waiting by the phone to be in a documentary about the Lampoon. Mostly because they felt no one could tell (the story) properly. In some cases, people didn’t want to talk because they still had some wounds or grudges from their time at the magazine.”

“Wired,” Bob Woodward’s less than flattering portrait of John Belushi, also cast a long and lingering shadow. “That did not help us, no doubt about it,” Tirola said.

For Poon-heads, there are great stories in Tirola’s film about the volatile Michael O’Donoghue, who was poached by “Saturday Night Live” (he was “Mr. Mike,” teller of “Least-Loved Bedtime Tales”) and John Hughes, whose short story, “Vacation ‘58” inspired “National Lampoon’s Vacation.”

One of the surprises of the film is prickly personality Chevy Chase, who shares moving anecdotes about the late Kenney and Belushi, both felled by drugs and in Kenney’s case, depression. Chase’s participation got off to an inauspicious start, Tirola recalled, with Chase making disparaging comments about his shoes (white bucks after Labor Day) and Tirola’s questions (“I just want you to know that question is longer than any answer I’m going to give you today”).

But if Tirola has learned anything on a film set, it is this: never interrupt an actor while he’s performing. “My role was to be the straight man,” Tirola said. “I resisted the impulse to make a joke back to him. He was getting warmed up and at a certain point, he made a decision to give us a great [interview].”

The National Lampoon ceased publication in 1998. The magazine and the brand had long ceased to be comedically or culturally relevant. Sadly, there is a generation who only know the National Lampoon’s licensed name in association with such execrable straight-to-DVD releases as “Master Debaters” and “The Legend of Awesomest Maximus.”

Tirola spares us the brand’s sad decline. On this, he took his inspiration from “Rocky.”

“My understanding was when ‘Rocky’ was originally made, there was to be a “morning after” scene at the end where you see all the bruises and how messed up Rocky was, like that scene in ‘North Dallas 40’ with Nick Nolte barely able to move after the football game. Addressing the business turmoil would have really changed what we’re trying to say about the Lampoon. I wanted our movie to be a celebration of these artists’ work.”

“Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead” does an admirable job of encompassing the National Lampoon’s massive scope and influence. For those of a certain age, it throbs with an animated “wasn’t that a time” energy.

Re-reading issues of the Lampoon from its glory years, Tirola said, is like revisiting a movie you saw when you were 14. “It still means everything to you because you saw it at a certain age and it spoke to you in a certain way that you could only be spoken to at that age. That’s what I hope comes across in the movie.”