Herzog’s Minnesota Declaration: Defining ‘ecstatic truth’

Dear Werner,

You have done me the astonishing honor of dedicating your new film, “Encounters at the End of the World,” to me. Since I have admired your work beyond measure for the almost 40 years since we first met, I do not need to explain how much this kindness means to me. When I saw the film at the Toronto Film Festival and wrote to thank you, I said I wondered if it would be a conflict of interest for me to review the film, even though of course you have made a film I could not possibly dislike. I said I thought perhaps the solution was to simply write you a letter.

But I will review the film, my friend, when it arrives in theaters on its way to airing on the Discovery Channel. I will review it, and I will challenge anyone to describe my praise as inaccurate.

I will review it because I love great films and must share my enthusiasm.

This is not that review. It is the letter. It is a letter to a man whose life and career have embodied a vision of the cinema that challenges moviegoers to ask themselves questions not only about films but about lives. About their lives, and the lives of the people in your films, and your own life.

Without ever making a movie for solely commercial reasons, without ever having a dependable source of financing, without the attention of the studios and the oligarchies that decide what may be filmed and shown, you have directed at least 55 films or television productions, and we will not count the operas. You have worked all the time, because you have depended on your imagination instead of budgets, stars or publicity campaigns. You have had the visions and made the films and trusted people to find them, and they have. It is safe to say you are as admired and venerated as any filmmaker alive–among those who have heard of you, of course. Those who do not know your work, and the work of your comrades in the independent film world, are missing experiences that might shake and inspire them.

I have not seen all your films, and do not have a perfect memory, but I believe you have never made a film depending on sex, violence or chase scenes. Oh, there is violence in “Lessons of Darkness,” about the Kuwait oil fields aflame, or “Grizzly Man,” or “Rescue Dawn.” But not “entertaining violence.” There is sort of a chase scene in “Even Dwarfs Started Small.” But there aren’t any romances.

You have avoided this content, I suspect, because it lends itself so seductively to formulas, and you want every film to be absolutely original.

You have also avoided all “obligatory scenes,” including artificial happy endings. And special effects (everyone knows about the real boat in “Fitzcarraldo,” but even the swarms of rats in “Nosferatu” are real rats, and your strong man in “Invincible” actually lifted the weights). And you don’t use musical scores that tell us how to feel about the content. Instead, you prefer free-standing music that evokes a mood: You use classical music, opera, oratorios, requiems, aboriginal music, the sounds of the sea, bird cries, and of course Popol Vuh.

All of these decisions proceed from your belief that the audience must be able to believe what it sees. Not its “truth,” but its actuality, its ecstatic truth.

You often say this modern world is starving for images. That the media pound the same paltry ideas into our heads time and again, and that we need to see around the edges or over the top. When you open “Encounters at the End of the World” by following a marine biologist under the ice floes of the South Pole, and listening to the alien sounds of the creatures who thrive there, you show me a place on my planet I did not know about, and I am richer. You are the most curious of men. You are like the storytellers of old, returning from far lands with spellbinding tales.

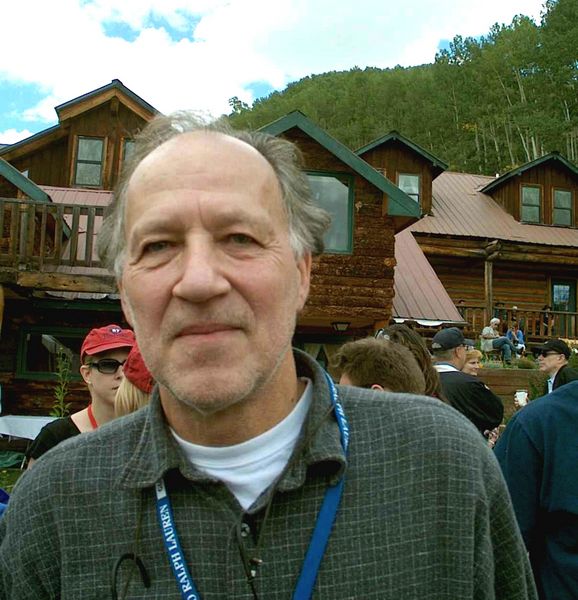

I remember at the Telluride Film Festival, ten or 12 years ago, when you told me you had a video of your latest documentary. We found a TV set in a hotel room and I saw “Bells from the Deep,” a film in which you wandered through Russia observing strange beliefs.

There were the people who lived near a deep lake, and believed that on its bottom there was a city populated by angels. To see it, they had to wait until winter when the water was crystal clear, and then creep spread-eagled onto the ice. If the ice was too thick, they could not see well enough. Too thin, and they might drown. We heard the ice creaking beneath them as they peered for their vision.

Then we met a monk who looked like Rasputin. You found that there were hundreds of “Rasputins,” some claiming to be Jesus Christ, walking through Russia with their prophecies and warnings. These people, and their intense focus, and the music evoking another world (as your sound tracks always do) held me in their spell, and we talked for some time about the film, and then you said, “But you know, Roger, it is all made up.” I did not understand. “It is not real. I invented it.”

I didn’t know whether to believe you about your own film. But I know you speak of “ecstatic truth,” of a truth beyond the merely factual, a truth that records not the real world but the world as we dream it.

Your documentary “Little Dieter Needs to Fly” begins with a real man, Dieter Dengler, who really was a prisoner of the Viet Cong, and who really did escape through the jungle and was the only American who freed himself from a Viet Cong prison camp. As the film opens, we see him entering his house, and compulsively opening and closing windows and doors, to be sure he is not locked in. “That was my idea,” you told me. “Dieter does not really do that. But it is how he feels.”

The line between truth and fiction is a mirage in your work.

Some of the documentaries contain fiction, and some of the fiction films contain fact. Yes, you really did haul a boat up a mountainside in “Fitzcarraldo,” even though any other director would have used a model, or special effects. You organized the ropes and pulleys and workers in the middle of the Amazonian rain forest, and hauled the boat up into the jungle. And later, when the boat seemed to be caught in a rapids that threatened its destruction, it really was. This in a fiction film. The audience will know if the shots are real, you said, and that will affect how they see the film.

I understand this. What must be true, must be true. What must not be true, can be made more true by invention. Your films, frame by frame, contain a kind of rapturous truth that transcends the factually mundane. And yet when you find something real, you show it.

You based “Grizzly Man” on the videos that Timothy Treadwell took in Alaska during his summers with wild bears. In Antarctica, in “Encounters at the End of the World,” you talk with real people who have chosen to make their lives there in a research station. Some are “linguists on a continent with no language,” you note, others are “PhDs working as cooks.” When a marine biologist cuts a hole in the ice and dives beneath it, he does not use a rope to find his way back to the small escape circle in the limitless shelf above him, because it would restrict his research. When he comes up, he simply hopes he can find the hole. This is all true, but it is also ecstatic truth.

In the process of compiling your life’s work, you have never lost your sense of humor. Your narrations are central to the appeal of your documentaries, and your wonder at human nature is central to your fiction. In one scene you can foresee the end of life on earth, and in another show us country musicians picking their guitars and banjos on the roof of a hut at the South Pole. You did not go to Antarctica, you assure us at the outset, to film cute penguins. But you did film one cute penguin, a penguin that was disoriented, and was steadfastly walking in precisely the wrong direction–into an ice vastness the size of Texas. “And if you turn him around in the right direction,” you say, “he will turn himself around, and keep going in the wrong direction, until he starves and dies.” The sight of that penguin waddling optimistically toward his doom would be heartbreaking, except that he is so sure he is correct.

But I have started to wander off like the penguin, my friend.

I have started out to praise your work, and have ended by describing it. Maybe it is the same thing. You and your work are unique and invaluable, and you ennoble the cinema when so many debase it. You have the audacity to believe that if you make a film about anything that interests you, it will interest us as well. And you have proven it.

With admiration,

Roger