A long, long time ago—the late 1970s, to be exact—a dear friend of mine, a very talented cartoonist, began taking classes at New York’s School of Visual Arts. He had two famous instructors. One was Harvey Kurtzman, a founder of MAD Magazine, and a congenial, anarchic talent. My friend liked him a lot and found an easy affinity with him. The other was a more underground figure named Art Spiegelman. My friend was initially aghast. “He drew a multi-page cartoon strip about his mother committing suicide,” he told me. He considered this a rather terrible act of disrespect. (At the time he was still living in the house he grew up in and indeed lived there until the day he died, with his mother until her death and then with his brother.) “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” is the name of Spiegelman’s 1972 work, and it is still a galvanizing and upsetting piece of art. Eventually, my friend came to see that it was not disrespectful as such but had a brutal honesty that turned mostly on Spiegelman himself. He eventually appreciated its almost unprecedented integrity. But he never got comfortable with it.

And, indeed, it is a work that is still discomfiting to revisit. It’s reproduced in the book Breakdowns, an apt title for a collection of Spiegelman art. The volume remains bracing; if you only know Spiegelman from his considerably tamer (but nevertheless still provocative) work for The New Yorker magazine, Breakdowns is apt to blow off the top of your head.

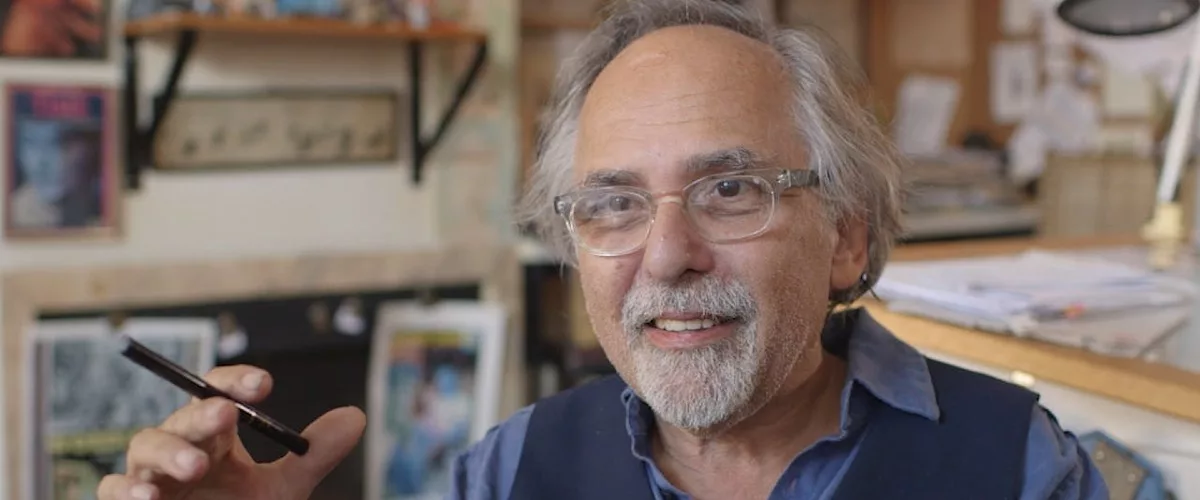

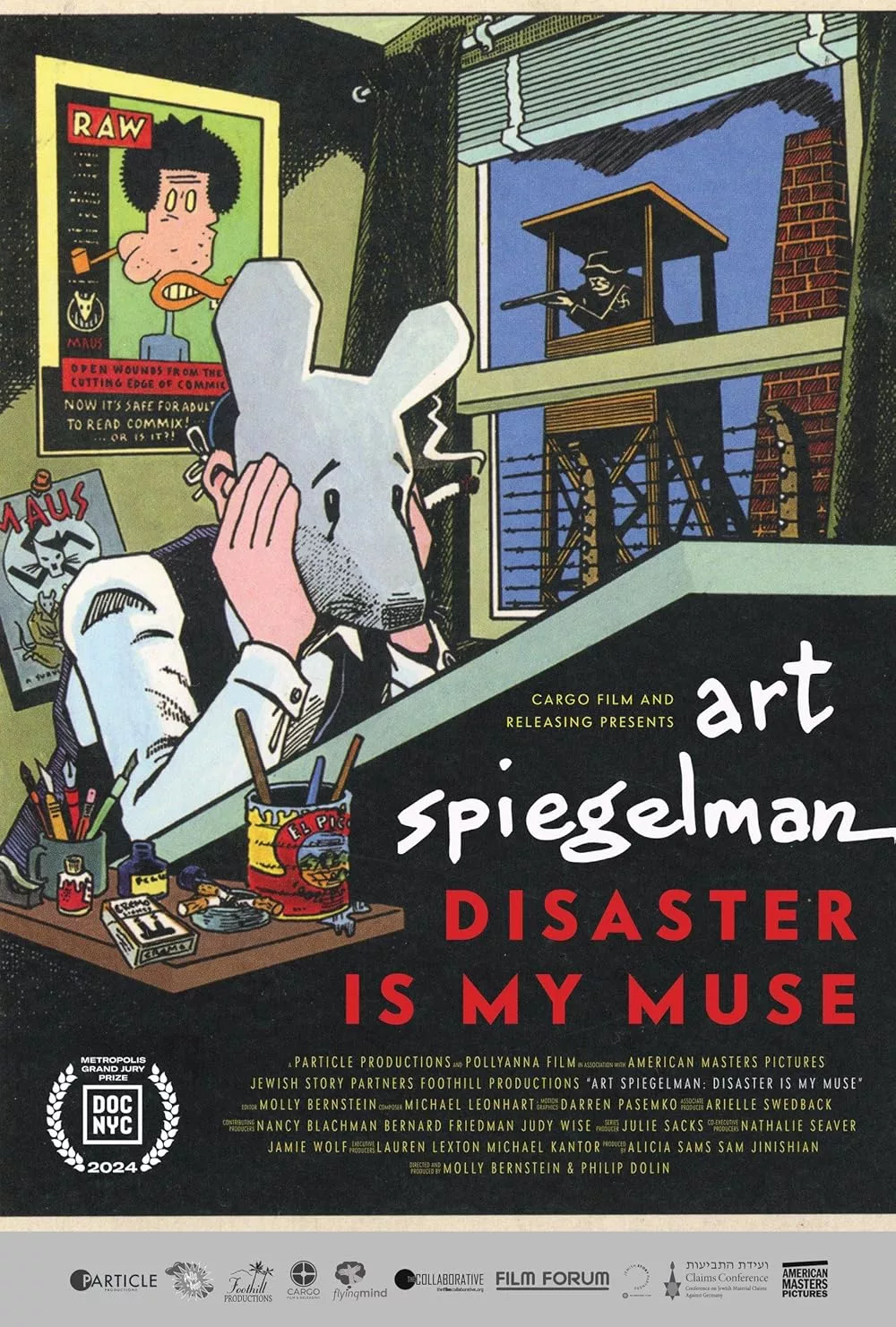

As he presents himself publicly, Spiegelman, who is now 76 years old, the artist is voluble if not quite avuncular. His life work (for better or worse as far as he’s concerned, as we learn) was the incredible graphic novel—although calling it a “novel” is inaccurate, and when these books hit The New York Times Best Seller Lists, Spiegelman insisted on their being categorized, accurately, as non-fiction, and the Times complied—Maus, an autobiographical two-part work about Spiegelman coming to grips with not just his own past but that of his father, a Holocaust survivor. The Shoah, of course, is also central to the story of Spiegelman’s mother. Maus pulls these threads together with unstinting frankness, remarkable craft and artfulness, and, occasionally, very mordant humor. The work gained huge popularity, and earned him a Pulitzer Prize, and then dogged him; he couldn’t get out from under it. In an apt demonstration of the subtitle of “Art Spiegelman: Disaster Is My Muse,” it was 9/11—an event he and his daughter were such close eyewitnesses to that they were nearly wiped out by it—that gave him a new subject and yielded In The Shadow Of No Towers.

Directed by Molly Bernstein and Philip Dolin, “Art Spiegelman: Disaster Is My Muse” is a remarkably cogent and compelling presentation not just of Spiegelman’s life story but also his personality and art. The narrative of his career, with roots in San Francisco and underground comix, is related at a dinner table, with the legendary artists R. Crumb and Aline Kominsky-Crumb, back-in-the-day colleagues of the subject. Spiegelman’s wife Françoise Mouly, now the art editor of The New Yorker, is there as well. Spiegelman still kvells at the great good fortune he had to get a job with Topps, manufacturer of bubblegum and, more importantly, bubblegum cards, where he created “Wacky Packages,” irreverent sendups of consumer product art. It paid well and was “a gig whenever I wanted.” Such work helped subsidize the creation of his still-impressive large-format comics magazine Raw. To this day, Spiegelman has his head down at the drawing board almost constantly.

He’s very articulate about his work. Discussing Maus, he’s inclined to talk more about how he structured it than its content, which of course is overt anyway. He explains why he wanted the graphics on Hell Planet to be in the style of woodcuts, and how he used a scratch pad to achieve that. And so on. The film critic J. Hoberman, who was a college buddy of Spiegelman’s, is illuminating, as is the avant-garde filmmaker Ken Jacobs (and wife Flo and son Azazel, himself a filmmaker of course), also a friend and compere of Art’s. It’s fascinating to be led through the influences on the artist, including that of Bernie Krigstein, whose EC Comics story Master Race was a precursor to Maus.

The movie ends on a bleak note, with Spiegelman observing the first Trump administration and bemoaning a new wave of fascism. “We’ve gone from ‘never again’ to ‘never again and again and again,’” he says. One can’t imagine that he’s too thrilled by current events. But one is confident that he’ll produce some work that’s appropriate to the present moment.