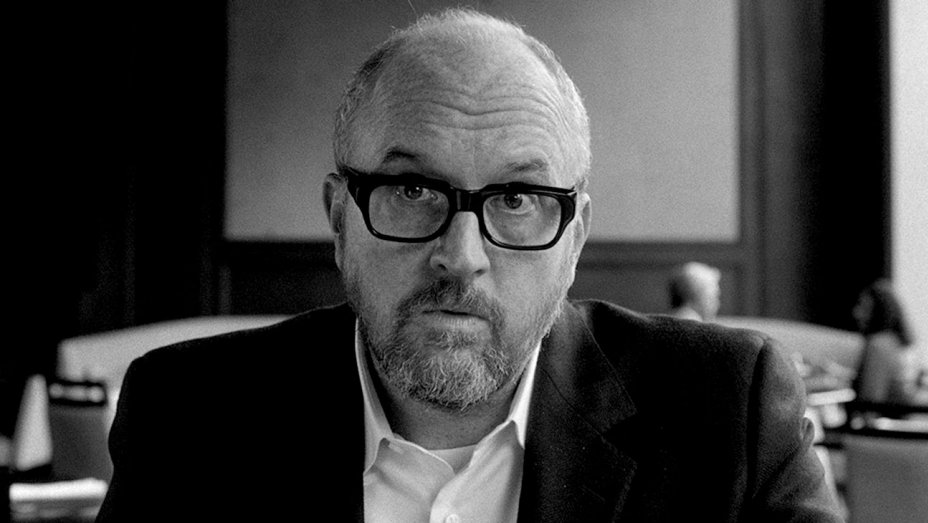

Let’s get a few things out of the way with regards to Louis C.K.’s new feature “I Love You, Daddy”: Photographed by longtime collaborator Paul Koestner on black-and-white film, “I Love You, Daddy” is a formal allusion/response to Woody Allen’s “Manhattan,” and to a lesser extent “Crimes and Misdemeanors.” It centers on a successful TV creator (played by C.K.) who struggles when his 17-year-old daughter (Chloë Grace Moretz) begins to see his 68-year-old idol (John Malkovich), an acclaimed writer/director who has a predilection for young girls and has been accused of molestation. Malkovich’s character is designed to recall Allen specifically, or is at the very least a composite of other successful men with, shall we say, controversial personal lives. The film’s narrative is further problematized by rumors of C.K.’s own sexual impropriety, as its recurring dialectic about the separation of art/artist, the limitations of plausible deniability, and the inherently unknowable nature of individuals actively forces the audiences to consider these extratextual ideas.

If this scans to you as an a priori disreputable subject for a film, I’m not sure if I have a great argument against that. For what it’s worth, C.K. doesn’t treat the subject glibly. He doesn’t posit easy or shallow answers to the film’s primary questions and its central issues are never resolved. They’re just further complicated and debated again and again. Suffice it to say, “I Love You, Daddy” is, by design, a profoundly uncomfortable film. During the TIFF screening I attended, there were moments when you could feel the air get sucked out of the room and hear actual seat squirming. Mileage will inevitably vary if that discomfort is justified by the film’s quality, and if this section of the dispatch reads at all wishy-washy, it’s because I’m still grappling with that question as well.

C.K.’s entire career has been predicated upon a somewhat confrontational approach; his stand-up and his TV shows frequently frame similarly challenging questions in a comedic light and then examine their various facets. Though the premise of “I Love You, Daddy” will be undeniably and appropriately read as a provocation, it ultimately tries to get across two simple, non-provocative ideas: 1) “difficult” conversations immediately become less difficult when they’re no longer an abstraction; and 2) no one will ever know the full truth about anybody, so all we’re left with are assumptions and limited information. In the film, C.K.’s character Glen Topher and his daughter, China, spot Malkovich’s Lesley Graham at a glitzy party in the Hamptons. China immediately repulses and calls him a child molester, but Topher chastises her, saying that those are just rumors and that she doesn’t actually know him. However, Topher quickly becomes horrified when China and Graham start hanging out and all talk about “rumors” goes straight out the window. Neither Topher nor China really knows the full truth about Graham, and yet when personal stakes contextualize the immediate situation, the truth becomes irrelevant to both of them.

“I Love You, Daddy” implicitly and explicitly asks a variety of questions that all but demand a conflicted response from its audience. Does a person stop being a “minor” psychologically when they turn 18? Does a father have a right to demand anything from his daughter if he didn’t actually raise her? Are you still empowered when you willfully submit to manipulation? Does privilege, both racial and economic, afford people to intellectualize ostensibly cut-and-dry moral issues? Given that you can’t really know anybody, is it worth it to try? And so on and so forth. Again, the film doesn’t answer any of these questions. Instead, it simply wades in their murkiness and allows the audience to do the heavy lifting.

It should be said that “I Love You, Daddy” suffers from flaws that have nothing to do with its subject matter. For one thing, C.K.’s digressive style doesn’t quite work with this film, and at two hours long, it frequently drags. It can be argued that Koestner’s gorgeous photography and Robert Miller and Zachary Seman’s lush classical score never quite transcend its homage. Though it boasts a great supporting cast that includes Edie Falco, Rose Byrne, and Helen Hunt, some of the performances aren’t exactly up to snuff, especially Charlie Day’s, whose scenes are too broad and frequently unfunny (although, to his credit, he does have the funniest line and line-reading in the film by far.) But most of all, it isn’t that funny, but it’s unclear if that’s in line with the formal framing or not.

While “I Love You, Daddy” pales in comparison to C.K.’s “Louie” and “Horace and Pete,” two of the very best TV shows of the last decade, it’s the one film that hasn’t left my mind since I exited the theater. It doesn’t errantly perturb or rest on its incendiary laurels, but asks more of its audience than usually asked, and that’s at least worth consideration.

Scott Cooper’s latest film “Hostiles,” a western that doubles as a belabored exercise in allyship, follows Captain Joseph J. Blocker (Christian Bale), a ruthless soldier who has mercilessly fought Native Americans in many conflicts, as he’s tasked with delivering dying Cheyenne chief Yellow Hawk (Wes Studi) to his homeland in Montana. Along the way, he encounters Rosalie Quaid (Rosamund Pike), a woman who witnessed the murder of her husband, two children, and infant at the hands of the Natives, and takes her along with his detail. On the way to Montana, Blocker, Rosalie, and the rest of his company (some of whom are played by Jesse Plemons, Timothée Chalamet, newcomer Jonathan Majors, and an utterly unrecognizable Rory Cochrane) confront the sins of their military past and learn to understand the Native American plight, all while taking heavy casualties at the hands of white and non-white men.

Though it features some poetic landscape photography courtesy of Masanobu Takayanagi, “Hostiles” suffers from an overly dour tone and a projected sense of capital-I Importance that sinks the film by the halfway mark. While all the performances are base level compelling, they’re rooted in a superficial seriousness that can’t help but read as strained. Max Richter’s treacly score only underscores this fact, as well as Cooper’s direction that repeatedly highlights internal and external pain as a shortcut to drama. “Hostiles” conveys every emotion in bold block letters, never allowing the audience to reach any of its obvious conclusions on its own.

Moreover, “Hostiles” falls short of its lofty political ambitions. To the film’s credit, Cooper’s screenplay genuinely grapples with the atrocities that the United States government has committed against the Native people, albeit in a clumsily earnest manner. It places all the right talking points in the mouths of its characters, some of whom have arcs that take them from brutality to a place of understanding. It’s also worth noting that before its TIFF premiere, Cooper invited a Cheyenne chief onto the stage to bless the theater, and the chief’s wife made an emotional speech endorsing the film. Yet, it’s difficult to ignore the fact that the white characters still remain at the center of the film. Yellow Hawk and his family play a nice second fiddle to Blocker and Quaid, constantly providing encouragement and preaching tolerance, and that’s a little bit troubling considering that the film explicitly traffics in questions of atonement and forgiveness regarding the American ur-genocide. This is the obvious trade-off when you’re dealing with Hollywood stars and mid-budget productions, but nevertheless, when you’re making a film about Native suffering and potential reconciliation with their white oppressors, it’s not exactly an easy element to overlook.

Angela Robinson’s antiseptic “Professor Marston and the Wonder Women” initially plays like a twist on the traditional biopic formula, i.e. ignoring Marston’s comic book creation almost entirely to focus instead on his nontraditional personal life, but quickly succumbs to both romantic drama clichés and then standard paint-by-numbers biopic clichés. Marston (played by Luke Evans) indeed led an interesting life beyond his work, as he and his wife Elizabeth (Rebecca Hall, predictably excellent) embarked on a polyamorous relationship with Olive Byrne (Bella Heathcote). Their kinky sex life (relative to the norms of the early 20th century, of course), involving bondage play and BDSM, inspired the superhero and her powers, which inevitably led to controversy and outrage from decency groups as well as the masses. As the film repeatedly underlines, society simply wasn’t ready for the pointed symbolism of Wonder Woman nor Marston’s sex positive lifestyle with Elizabeth and Olive.

Indeed, Robinson’s nonjudgmental approach to Marston’s relationship sets the film apart, and the mildly steamy sex scenes are shot with consummate desire and care, but despite the surface level titillation, literally everything else about “Professor Marston and the Wonder Women” feels predictable and staid. The rise-and-fall-and-rise-again life story narrative, the ridiculous framing story that allows Marston, like Dewey Cox, to think about his entire life, the caricatured villains, the compressed identity politics, the us vs. them melodrama (Bella Heathcote honestly might be crying in 95% of her scenes), all of it has been done before. Robinson tries her hardest to spice up an old hat, but at the end of the day, it’s still the same damn hat that’s been around for years.

I saw Mélanie Laurent’s “Plonger” on the strength of her previous narrative feature “Respire” (released as “Breathe” in the United States), and while it doesn’t match it on a quality level, it does showcase Laurent’s genuine talent as a stylist. The film follows Paz Aguilera, an alienated, existentially adrift photographer (María Valverde), who struggles with her domestic life with her husband César (Gilles Lellouche) and their newborn, eventually abandoning them both for deep-sea diving off the coast of Yemen. The film’s first half functions as a compelling canvas for Laurent’s restless, elliptical filmmaking, capturing Paz’s internal state, which vacillates between joy and utter distress. On the other hand, the second half devolves into a much more programmatic mode, complete with a labored metaphor and narrative bow-tying that the film never previously tried to attempt. Nevertheless, “Plonger” confirms that Laurent’s status as a compelling filmmaker, even if it isn’t doesn’t match her earlier work.