For the residents of less populous parts of the world, marquee festivals are few and far between. It’s for this reason that Australian cinephiles cling to events like the Sydney Film Festival with a particular fervor and devotion. Although not as prominent as the top festivals in Europe or North America, SFF has, over the past few years especially, taken advantage of its calendar proximity to Cannes, nabbing major titles direct from the Riviera while giving patrons a rare chance to gloat to their international friends that, for once, we saw it first.

Case in point, the top prize in this year’s official competition went to “Two Days, One Night,” the latest work from two time Palme d’Or winners Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne. The kind of intimate portrayal of working class life for which the Belgian brothers have become known, the film stars Marion Cotillard as a depressed woman forced to fight for her job after her boss tells her co-workers they’ll lose their bonuses if the company keeps her on. Despite consisting of essentially the same conversation sixteen times over, the writer-directors never once feel like they’re repeating themselves. Each scene, shot in long handheld takes, has its emotional peaks and valleys, while every member of the cast brings something unique and memorable to their role.

Also from Cannes came “The Rover,” David Michôd’s hotly anticipated follow-up to his debut feature “Animal Kingdom,” and easily the most prominent of the three local films in competition. Yet while the pic’s technical panache cements Michôd as one of the country’s most talented technical filmmakers, the barebones plotting succumbs to a pervasive atmosphere of despair. Guy Pearce’s performance, as a merciless wanderer in a dystopian future outback, is disappointingly one note, while Robert Pattinson overacts as his slow-witted American counterpart. (As an aside, you can’t help but wonder if Michôd is trolling US audiences who can’t understand Australian accents by having Pattinson affect a Southern drawl so thick that it’s basically incomprehensible.)

A better Australian film from the Sydney line-up is “Ruin,” Amiel Courtin-Wilson’s follow-up to the aggressively experimental “Hail.” Shot on the streets of Phnom Penh, Courtin-Wilson and his first-time co-director Michael Cody hint at Cambodia’s traumatic past in their Badlands inspired story, about a downtrodden factory worker and a runaway prostitute who journey into the wilderness in the wake of a brutal murder. A film more concerned with sight and sound than with narrative, the minimal plotting and elliptical imagery may alienate some, although the movie will almost certainly be less divisive than Courtin-Wilson’s previous effort. Either way, for those who are willing to let it wash over them, “Ruin” is transcendently beautiful.

The final Australian film competing for gold came from first time director Kasimir Burgess: “Fell” concerns two men struggling with grief and guilt after a little girl is killed in a hit and run. The first man is the girl’s father. The second is the man who was driving the truck. Burgess exhibits some early teething problems, particularly in his unconvincing set-up in the scenes immediately following the accident. The film really comes into its own in the second half, however, as it transitions into a tense and ambiguous morality play steeped in questions of revenge, responsibility and forgiveness. Not an entirely successful debut, but good enough to make Burgess well worth keeping an eye on.

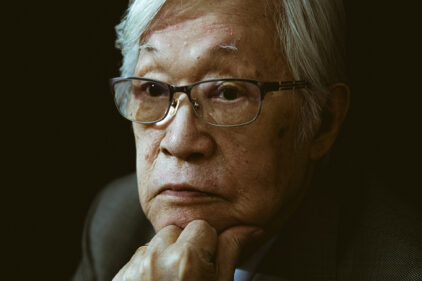

A distinct international highlight amongst the competition films, meanwhile, was Diao Yinan’s immaculately photographed thriller “Black Coal, Thin Ice,” which took Berlin’s Golden Lion back in February. An archetypal film noir complete with gruesome murders, an icy femme fatale and a washed up former cop looking for a chance at redemption, the cryptic plot machinations are largely secondary to some of the most striking cinematography in quite some time. While rarely overt, every frame of this film holds purpose, while images frequently take on new meaning the longer the camera holds its gaze.

Amongst the remaining competition features were a pair of films that experimented with continuity, although they did so in very different ways. Much has been made of Richard Linklater’s twelve year shooting schedule on “Boyhood,” a film that, although extraordinarily conventional from a narrative perspective, proved a favourite with SFF audiences. Less accessible is Shahram Mokri supposed slasher movie “Fish & Cat,” filmed in a single, 134 minute take in a campsite outside of Tehran. While the concept sounds interesting, the handheld execution is pretty unremarkable. Worse is the plot, which is meandering, inaccessible and dull.

Moving beyond the official contest, one of the most remarkable films came in the form of “All This Mayhem.” A locally produced documentary, director Eddie Martin tells the story of Melbourne-born skateboarding duo Tas and Ben Pappas, each of whom challenged Tony Hawk for the position of world number one. Whatever intense disinterest you might initially feel towards the subject matter, know that what “Senna” did for F1, this film does for skateboarding. Wild, exhilarating and frequently heartbreaking, it’s hard to imagine many better docs being released in 2014.

Not that there wasn’t stiff competition from within the Sydney program. Few movie lovers could watch “Jodorowsky's Dune” without grinning like an idiot. The master of surrealist cinema makes for a fascinating and highly enthusiastic interview subject, expounding at considerable lengths on the single greatest movie never made. A film similarly well-suited to festival audiences is “Life Itself,” a documentary that in these parts surely needs no introduction. At Sydney, the film was introduced by David Stratton, a veteran critic and the co-host of Australia’s own At the Movies program inspired by Siskel and Ebert. While Roger may not have been a household name on this side of the world, the impact he had on the local critical industry cannot be overstated.

Closing night film crossed the ditch from New Zealand, along with co-directors Taika Waititi and “The Flight of Conchords” star Jermaine Clement. A delightful mockumentary, “What We Do in the Shadows” explores the living conditions of four vampires who share an apartment in downtown Wellington. With a mix of macabre black humour and hilariously awkward banality, the film is very much in keeping with the films of Christopher Guest, albeit with a few more disembowelments. It doesn’t reinvent the wheel, but it’s an enormous amount of fun, and a suitably light-hearted way to bring the festival to an end.