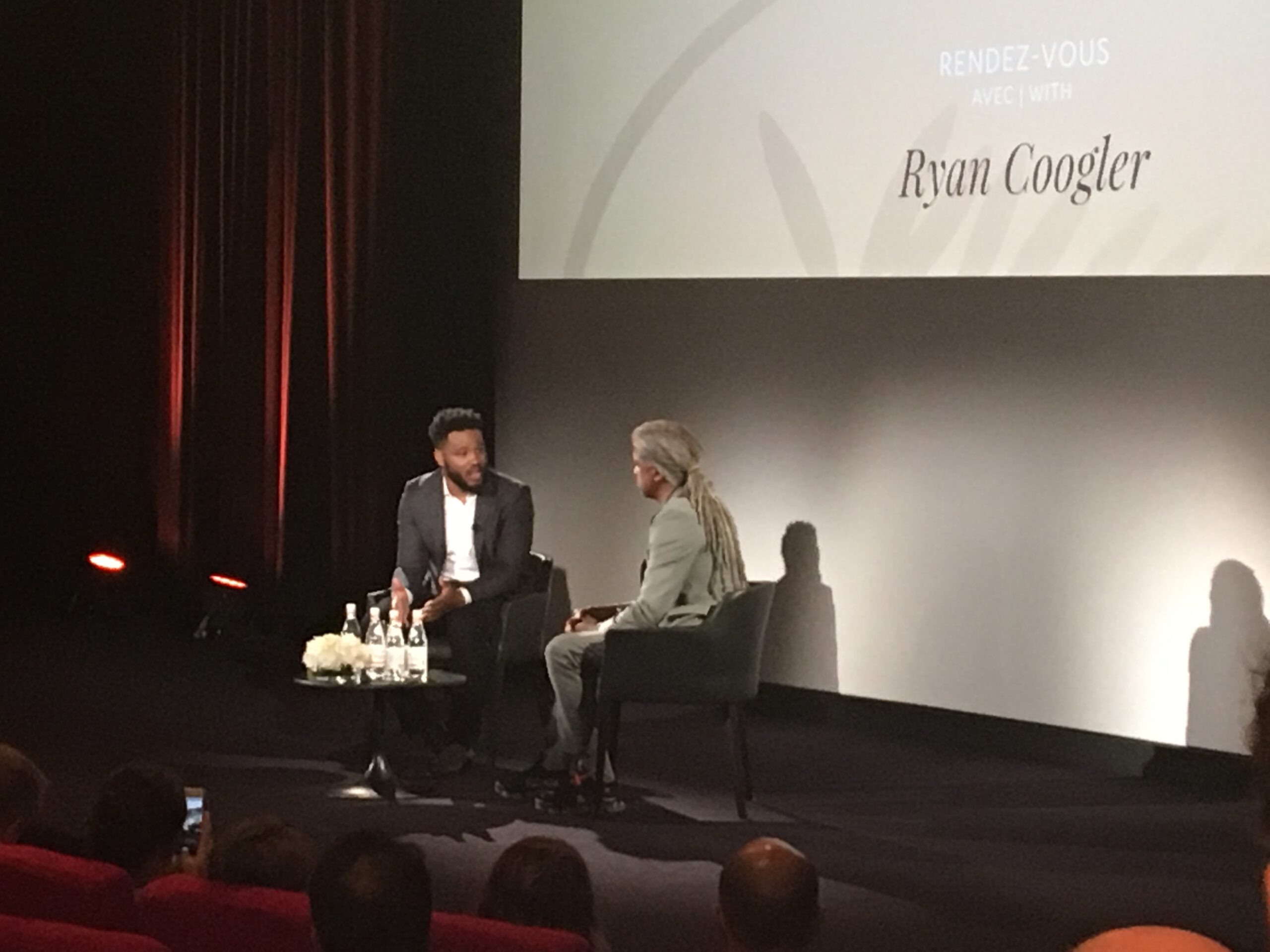

After earning more than $1 billion in global box office with “Black Panther,” Ryan Coogler had to settle for being (merely, probably) the hottest ticket in Cannes on Thursday afternoon, when a crowd scrummed outside normally placid Salle Buñuel, hoping to sit in on a conversation between the filmmaker and Elvis Mitchell. The Buñuel is the auditorium where the festival normally holds its master classes, which this year are rather charmingly being called “rendez-vous.” No matter what you call it, a master class is not a bad gig for a 31-year-old director.

It was a return to Cannes for Coogler, whose debut feature, “Fruitvale Station,” screened here in 2013 after winning the top prize at Sundance that year. “My first time I’d ever been out of the country was at this festival,” he said, “and it changed my life as a filmmaker.”

Mitchell pointed out that Coogler had brought 60 students to the rendez-vous. “I’ve had an opportunity to do a lot of film festivals and a lot of talks in the past, and sometimes it can be challenging in a talk when you look out and you don’t see faces that look like yours,” Coogler explained. “And I just remember being in film school.” Wanting to share what he had experienced at Cannes, he brought in young filmmakers from locally, from Paris, and from Africa.

Over 90 minutes, he and Mitchell bantered about influences, the themes that have run through Coogler’s three features (“Creed,” his sharp and nuanced version of a Rocky sequel, being the second), and how he approached working with Marvel.

Coogler remembered cinematic experiences he shared with his parents, whether it was the impact of seeing “Boyz N the Hood” and “Malcolm X,” released when he was 5 and 6, in theaters with his father, or watching his mother (whom he described as “IMDb before there was IMDb”) acting out “The Fugitive” for him shortly after she saw it.

The range of movies that influenced “Black Panther” is eclectic and varied. Coogler looked to “The Godfather” as a template for a drama about a man stepping into a position of power. (“I was worried about people thinking we were aiming too high,” he said.) Ron Fricke’s “Baraka” and “Samsara” became examples of films that allow you to experience different cultures. The recent Cannes favorites “Timbuktu” and “Embrace of the Serpent” were also on his viewing list.

Coogler also tried to capture the feeling of visiting Africa for the first time, he said, “because we’re going to the continent for the first time as an audience.”

Mitchell said he sees Coogler’s three features as a trilogy; all deal with what happens to young black men without fathers in America. Coogler acknowledged that continuity while wondering the degree to which the theme might be subconscious in “Fruitvale Station,” for which he was trying to pay homage to the life of Oscar Grant.

Even so, he said that a lot of his friends didn’t have fathers growing up, and that that was sometimes a source of tension between him and them. “It’s something I’ve always been interested in—that father-son dynamic and what it means specifically in an African American community,” he said.

The themes of coming of age and death, he and Mitchell agreed, reverberate through all three films. “When I was 22,” the age at which Grant was fatally shot by a transit officer, Coogler said, “I hadn’t been to Cannes yet. I hadn’t even left the country yet. I didn’t know who I was just yet.”

He described “Black Panther” as a coming of age story for both T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman) and Wakanda. He also described how he approached the rivalry between T’Challa and Eric Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan), and what makes each character unique.

T’Challa is “a black man who is unaffected by colonization,” he explained. “I never heard about a black character like that in history.”

He added, “That’s the fundamental difference between him and Killmonger,” whom he likened to Batman without wealth. Coogler said that Marvel’s main pitch was that Black Panther should become the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s equivalent of James Bond. (Coogler admitted, with embarrassment, that he had seen “Austin Powers in Goldmember” before his first viewing of “Goldfinger.”)

Mitchell said that while the success of “Black Panther” disproved the Hollywood myth that films that tell black stories don’t travel, he feared that decision makers wouldn’t learn that lesson.

“At the end of the day it’s a business, right?” Coogler said. “And the business is informed by all of these things that life is informed by, colonization, institutional bias, racism. The business was built amongst all these things.” He remembered his father telling him about the time when baseball and basketball teams feared that having black players would drive spectators away.

When Mitchell pointed out that Hollywood may try to excuse the success of “Black Panther,” writing it off as simply the success of a Marvel property or as another hit from the director of “Creed,” Coogler replied, “How do you rationalize ‘Get Out’?”