What does it take to get your film into a world class festival? That’s the question asked with gleeful irreverence by “The Woman in the Septic Tank,” which screened at the recently concluded 2012 Berlinale, one of the world’s foremost festivals. This hilarious satire of international art filmmaking finds two aspiring auteurs sitting in a Manila café, jealously regarding a rival’s Facebook photos taken at the Venice film fest. They vow to devise the ultimate movie to win festival audiences and prizes: a single mother of five suffering in the slums is forced to sell her son to a rich pedophile. But like Mel Brooks’ “The Producers” (1968), the project gets out of hand, and before we know it we’re watching a musical version with the pedophile singing “Is this the boy / who’ll bring me endless hours of joy?” It’s one of many delightful detours taken by these filmmakers seeking the road to art house glory.

Some critics find “Septic Tank’s” satire too glib and cynical of the festival scene, but much of what it mocks can be found in another Filipino film that competed for the Berlinale’s prestigious Golden Bear. Brilliante Mendoza is one of the standard-bearers of the blistering DIY filmmaking that thrives in the Philippines (and with an ego to match: his website describes him as a “living national treasure.”) His success led to a golden ticket in the form of European funding, but his new film “Captive” finds him caught in the crossroads of no-budget trash filmmaking and festival prestige picture, doing service to neither. This hyperactive re-enactment of a 2001 terrorist incident even has Isabelle Huppert along for the ride as a kidnapped missionary, but it feels more like Michael Bay than Michael Haneke. From close-ups of menacing jungle creatures to a real baby being pulled out of a woman during a firefight, no attempt at sensationalism is spared to get a rise out of the audience.

Even one of the best films at Berlinale bears a whiff of third world exploitation. Miguel Gomes won two prizes for his second feature “Tabu,” a beguiling two-hander about a dying lady in Lisbon with a tragically romantic past. Her backstory unfolds in hypnotic fashion over a lush African plantation setting that’s more a nod to Hollywood and European movie fantasies than anything resembling what really was. It’s a Tarantino movie for art house romantics, and one I find brilliantly unique in its synthesis of so many references mined from all of film history. And yet it’s blinkered in its inability to break through the longstanding colonialist attitudes found in movies about Africa, instead employing them to cast an equatorial spell on the audience.

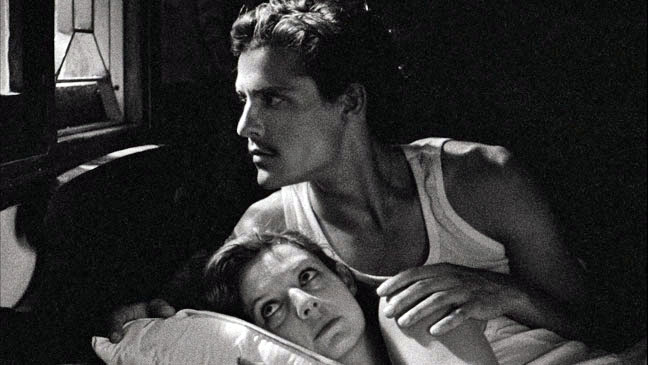

The Berlinale jury awarded its Best Picture Golden Bear to “Caesar Must Die,” Paolo and Vittorio Taviani’s audience-pleaser that stages Julius Caesar among Italian prison inmates. The film moves freely between straight performances of the play to moments where the actors break character to discuss how Shakespeare’s classic play of power and betrayal relates to their own personal misfortunes. Brilliantly staged and handsomely shot in black-and-white, it still feels like a loose series of vignettes with tangential interest in the players’ lives.

Outside the competition, German master Werner Herzog offered a more probing look at the lives and minds of inmates with “Death Row,” a four hour TV series extension of his great documentary of last year, “Into the Abyss: A Tale of Death, A Tale of Life.” At one point, Herzog argues with a Texas DA over a female death row inmate whom the DA fears Herzog will humanize through his film. Herzog replies, “I do not attempt to humanize her. She is already simply a human being.” It’s an eloquent statement that embodies Herzog’s sober approach to the cold facts and human mysteries governing lives condemned to die, while also making evident the absurdly callous and punitive nature of the Texas justice system.

Another German film was to my mind the best in competition. Compared to more flashy high-concept works like “Caesar Must Die” and “Tabu,” “Barbara” plays as a quiet throwback to old-school character drama. An East German woman doctor bides her time in a country hospital while seeking an opportunity to escape to the West. She’s increasingly distracted by a doting colleague, who’s either romantically interested, spying on her, or both. Moreso than the hit Stasi spy film “The Lives of Others,” there’s great attention and understatement to tiny shifts in character development and suppressed feeling from scene to scene. These are trademarks of the so-called “New Berlin School” of German filmmakers, who employ a stylistically precise approach to their films. “Barbara”‘s director, Christian Petzold, is perhaps the standout of this group, and deservedly won the Best Director Golden Bear.

American films made their mark in the festival’s Forum section with three adventurously eccentric portraits of off-the wall characters. In “Francine” Melissa Leo carries the show as a socially inept animal lover; her fearlessly committed performance reinforces her status as a national treasure for indie filmmakers. Paul Dano is less convincing as a rock singer trying to reunite with his estranged family in the wispy “For Ellen.” The raucous “Kid Thing” by David Zellner employs a saturated color scheme to reflect the mood swings of its 12 year-old girl protagonist as she wreaks havoc in a Texas town.

While affected at times, these efforts were all noteworthy for their attempts at uniqueness, but back in the competition lineup, the lone American feature gave eccentricity a genuinely lived-in feeling. “Jayne Mansfield’s Car” is Billy Bob Thornton’s first directing effort in 12 years, and the ambitious scope of this Southern epic family drama feels like he’s making up for lost time. Juggling an all-star ensemble including Robert Duvall, Kevin Bacon, John Hurt and Thornton, the film brings together a Georgian and a British family for a funeral, unearthing demons of the Deep South and Americana, specifically male infatuations with sex, war, and violent disaster. The film struck Berlinale critics as sloppy and overlong, but it’s chock-full of great acting, surprising little moments and an authentically personal worldview too compelling to ignore. Along with “Barbara,” it’s a special brand of festival film where the little things make it into a big deal.