“Into the Abyss” may be the saddest film Werner Herzog has ever made. It regards a group of miserable lives, and in finding a few faint glimmers of hope only underlines the sadness.

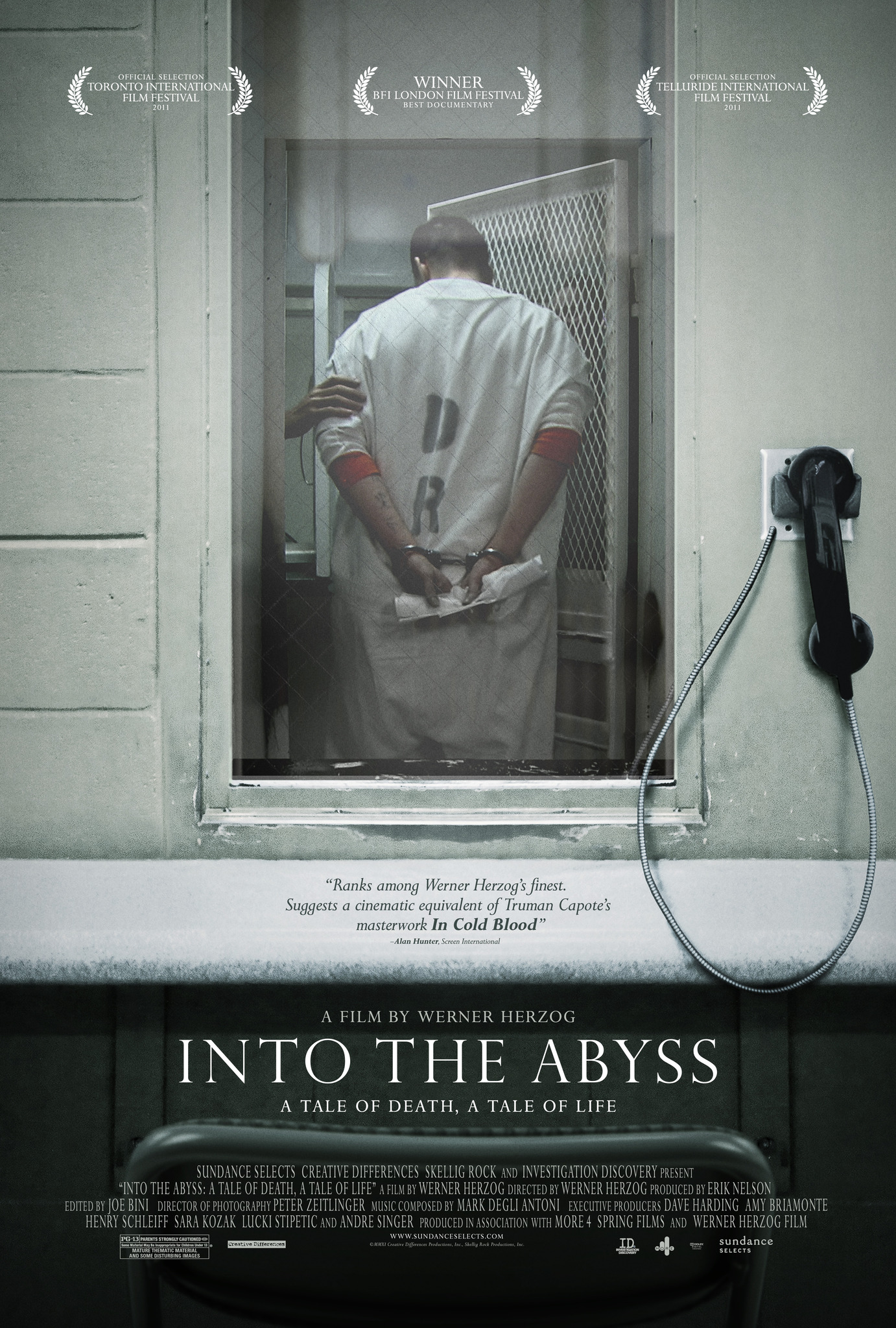

The documentary centers on two young men in prison. Michael Perry is on Death Row in Huntsville, Texas, America’s most productive assembly line for executions, and on the day Herzog spoke with him had eight days to live. Jason Burkett, his accomplice in the stupid murders of three people, is serving a 40-year sentence. They killed because they wanted to drive a friend’s red Camaro.

Herzog opposes the death penalty, which America and Japan are the only developed nations still imposing. But the film isn’t a polemic. Herzog became curious about the case, took a small crew to Huntsville and Conroe, Texas, where the murders took place, and spoke to the killers, members of their families and those of their victims. He obtains interviews of startling honesty and impact. I’ve learned that he met his subjects only once, on the day of the interviews, and the film presents their first conversations. I’ve long felt Herzog’s personality is compelling and penetrating, and in evidence I could offer this film about Texans who are so different from the German director.

Herzog keeps a much lower profile than in many of his documentaries. He is not seen, and his off-camera voice quietly asks questions that are factual, understated and simply curious. His subjects talk willingly. He asks difficult follow-up questions. He is not very interested in the facts (there is no doubt about guilt here), but in looking into the eyes and souls of people who were directly involved.

Why did Perry die and not Burkett, when both were convicted for the same crimes? We meet Burkett’s father, Delbert, who also is in prison serving a life sentence. In his testimony at his son’s trial, he blamed himself for the boy’s worthless upbringing. This apparently influenced two women jurors to pity the boy — or perhaps identify with the father. Delbert seems today a decent and reflective man. He bitterly regrets that he failed to take advantage of a college scholarship, dropped out of high school not long before graduation, and went wrong. He sees his mistake clearly now — too late for himself, too late for his son.

Perry and Burkett are uneducated, rootless, callow, lacking in personal resources. Delbert perhaps has benefitted from life in prison, as his son may. We meet Melyssa Burkett, who married Jason Burkett in prison and is now pregnant with his child — although, as Herzog observes, conjugal visits were not allowed. How did she become pregnant? She did, that’s all. Herzog never sensationalizes, never underlines, expresses no opinions. He listens.

We also meet Captain Fred Allen, who was for many years in charge of the guard detail on Huntsville’s Death Row, including the years in which George Bush turned down one appeal after another. He starts talking with Herzog and is swept up by memory and emotion, explaining why one day he simply walked away from his job and decided, after overseeing more than 100 executions, that he was opposed to the death penalty. What he has to say about one crucial event in his life is one of the most profound statements I can imagine about the death penalty.

The people in this film, without exception, cite God as a force in their lives. The killers, their relatives, the relatives of their victims, the police, everyone. God has a plan. It is all God’s will. God will forgive. Their lives are in His hands. They must accept the will of the Lord. Condemned or bereft, guilty or heartbroken, they all apparently find comfort in God’s plan. What Herzog concludes about their faith he does not say.

Opposition to the death penalty, in part, comes down to this: No one deserves to be assigned the task of executing another person. I think that’s what Captain Allen is saying. Herzog may agree, although he doesn’t say so. In some of his films he freely shares his philosophy and insights. In this film, he simply looks. He always seems to know where to look.