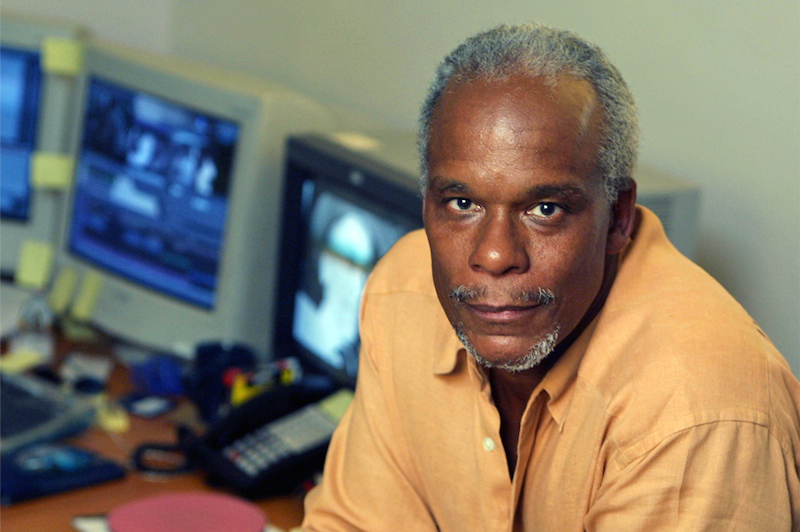

The words “STUDY THE PAST” are etched beneath a statue just outside the National Archives in Washington D.C. It’s a message that felt especially fitting last night, when filmmaker Stanley Nelson Jr.—a man who specializes in shedding light on past events sorely underrepresented in cinema—was honored at the AFI Docs festival’s annual Guggenheim Symposium held in the building’s William G. McGowan Theater. When walking toward the theater entrance, attendees can gaze at the Academy Award won by Charles Guggenheim for his 1964 short film, “Nine from Little Rock.” What made the National Archives doubly fitting as a venue in which to celebrate Nelson’s career is the fact that he—as observed by The Washington Post critic Ann Hornaday during her onstage interview with the director—has “perfected the art of working with archival material.”

Preceding Hornaday’s conversation with Nelson was a superb series of clips from his work that demonstrate just that: his use of intimate family photographs and rarely seen film footage provide audiences with a portrayal of African American life sorely lacking from the multiplexes. AFI president and CEO Bob Gazzale introduced the clips by drawing a connection between the recent tragedy in Charleston with the 1955 murder of Emmett Till, which was unforgettably chronicled in Nelson’s acclaimed 2003 film that ultimately led the U.S. Justice Department to reopen their investigation of the crime. Gazzale deemed Nelson “one of our nation’s preeminent historians,” a title he has earned by making such films as 1989’s endearing “Two Dollars and a Dream,” 2006’s galvanizing “Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple,” and his upcoming feature, “The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution,” that will screen to a sold out crowd at the festival this evening.

Once Nelson took to the stage, the symposium turned into one of this year’s liveliest festival highlights, as the filmmaker shared priceless stories with great charm and humor. He recalled how his past college professor, D.A. Pennebaker, was interested solely in cinema vérité, so much so that he began walking out of the classroom during a screening of Nelson’s thesis film simply because it was a work of fiction. “I need a grade!” Nelson protested, to which Pennebaker grunted, “Give yourself a grade.” “So I gave myself a 4.0,” Nelson laughed, as the packed audience broke into applause. He described how he wanted to make the audience “live the story” in his films as much as possible, while using music to push the narrative forward. When interviewing Alabama governor John Patterson for his 2009 film, “Freedom Riders,” he found that the man—whose legacy will forever be situated on the wrong side of history—simply wanted to talk about himself, as if thinking that by “getting it all out, he might be forgiven.”

Nelson revealed that his 2004 film, “A Place of Our Own,” the picture in his career that Hornaday regarded as her favorite, was originally intended to be a film about the black middle class before it evolved into an achingly personal portrait of his own family. “I was trying to make a film about my mother who had just passed,” Nelson recalled. “We got a new editor and she looked at the footage and said, ‘I think you’ve got a film here, but it’s not about your mother, it’s about your father.’ And I went, ‘Okay…you too can be fired!’” The editor’s instinct ended up saving the project, enabling the filmmaker to grapple with his troubled relationship with his father, who he had been estranged from for much of his life. The film primarily takes place at the black resort community, Oak Bluffs, located on Martha’s Vineyard, where Nelson spent four decades worth of summers. He struggled with the decision over whether to include candid footage of a conversation he had about the things black people do “in order to make white people comfortable,” before eventually keeping it in the final cut since it’s the sort of issue routinely missing from films. When Hornaday asked if he feels the burden of being “the explainer,” Nelson shook his head, arguing that he has no intention of being the African in “Tarzan” informing the white men about “what the drums mean.” “I’m making my films for black people,” Nelson said. “If they see something new in them, then obviously, white people will also see something new in them as well.” The director’s next film will focus on the history of black colleges and universities, while his company, Firelight Media, will continue to mentor emerging filmmakers with its Producers’ Lab.

Since her extraordinary 2006 feature debut, “Deliver Us From Evil,” which centered on a pedophile priest in the Catholic church, Amy Berg has been courageous in her efforts to expose sexual predators that keep their victims silent through the use of fear and power. Her upcoming film, “An Open Secret,” promises to illuminate abuse committed by high-ranking members of the movie industry, and is sure to create a great deal of controversy in Hollywood. At AFI Docs, Berg’s latest crime documentary, “Prophet’s Prey,” proved to be no less disturbing or vital than her other nonfiction work. Authors Jon Krakauer and Sam Brower detail their investigation into the polygamist cult of the Fundamentalist Church of Latter Day Saints, presided over by its “Prophet,” Warren Jeffs. Preaching the sacred importance of “giving up your will and obeying,” Jeffs would rape countless boys and girls, while marrying and impregnating various underage women. When his wives would inevitably fall into depression, he would prescribe them Prozac. One of his former wives remembers how she consciously broke her husband’s rule against wearing red (since he believed Jesus would one day return to Earth wearing red robes), in the hope that she would be killed and put out of her misery.

One of the most singularly appalling audio excerpts I’ve ever heard in a film plays out over a black screen, as we hear Jeffs having intercourse with a 12-year-old girl. The wedding photographs of his pre-teen brides straining to smile for the cameras are so unseemly that they deliver a visceral chill. Though Nick Cave, who composed the film’s score along with Warren Ellis, serves as the film’s narrator, much of the voice-overs consist of sermons delivered by Jeffs himself, who sounds strikingly like the HAL 9000 computer in “2001: A Space Odyssey.” When singing Bob Dylan’s classic, “Blowin’ in the Wind,” Jeffs sounds as inhuman as HAL did while warbling through “Daisy.” He would always warn his victims that if they ever told anyone about the abuse, they would be turning their back on God, and though Jeffs is currently enduring a life sentence behind bars, the control he has over his indoctrinated flock is reportedly stronger than ever. Producer Katherine LeBlond told me that prior to the film’s theatrical release in the Fall, additional footage would be added to explain how Jeffs’ obscene, seemingly inexplicable wealth has ties to Reliance Electric, Paragon Construction and Phaze Concrete. I am definitely planning on seeing the extended cut, though I’m grateful I won’t have to revisit the footage for a few months.

Easily the most purely enjoyable film I’ve seen thus far at AFI Docs 2015, two-time Oscar-winner Barbara Kopple’s latest crowd-pleasing masterwork, “Hot Type: 150 Years of The Nation,” profiles the staggering history of the titular, left-leaning weekly magazine. In a spectacular opening credit sequence, the camera pans from right to left, surveying pairs of hands typing away on computer keyboards and then archaic typewriters, as we are taken back through time. The first line of the first article in the first issue published in 1865 set the tone for everything to follow, demonstrating that the publication would avoid sensationalism in all forms: “This week has been singularly barren of exciting events.” It makes sense that a magazine without cigarette ads would be among the first to report on the link between smoking and cancer. Though The Nation has consistently been ahead of its time, the majority of its current subscribers are age 60 and over, causing editor Katrina vanden Heuvel to search for ways to reach a younger demographic. As a former intern who began working for The Nation in 1980, vanden Heuvel values the views of young people, and appears excited and moved to be in the process of passing the baton to the next generation.

Kopple was equally moved while introducing the film, saying that it was special for her to be screening her own work at the Naval Heritage Center, since she is currently working on a film about homeless veterans for Al Jazeera. There are many big laughs in “Hot Type” that are largely generated by the sheer charisma of the publication’s staff. Upon leaving a particularly torturous assignment, one writer quips, “Another day, another dollar—which in the case of The Nation is literal.” Stealing all of her scenes is the adorable daughter of executive editor Betsy Reed, Georgia Reed-Stamm, who eloquently verbalizes her own developing beliefs while analyzing the complaints of her conservative peers. The most effective aspect of the film is how it links current topical stories investigated by The Nation with articles that previously ran in the magazine several decades ago. “History tells you that you’ve been here before,” notes journalist John Nichols in the aftermath of Wisconsin governor Scott Walker’s victory in the much-publicized 2012 recall election, as Kopple cuts to The Nation’s coverage of Wisconsin senator Joseph McCarthy’s own improbable reelection. I’m reminded again of those words etched outside the National Archives, and am compelled to etch a few more beneath them: “STUDY THE PAST, OR YOU WILL BE DOOMED TO REPEAT IT.”

Full disclosure: My cousin, Jeremy Scahill, previously wrote for The Nation, and appears briefly in the film.