A frightened buffalo faces down the audience. Large, red and tattered claw marks rip through the canvas. The earthy color of the buffalo is soaked with blood. It’s a painting of fear, and as this enormous beast faces off against death, it’s mouth drops, and its eyes widen. With his back turned to the camera, a young Abel Ferrara stars as Reno in “The Driller Killer.” He looks his creation in the eye; it’s clear that Reno’s rage, uncertainty and fear has found its way into his art. The painting has become his obsession, the need to finish it a desperate spiritual and survival need. “The Driller Killer” is a race to see if he can complete it on time to settle his scores and whether it’s finality will quiet his impulsive and violent demons.

Ferrara’s films ripple with intensity. He’s a filmmaker who defies easy categorization, working across various genres, budgets and countries. Ferrara’s movies, above all else, boil over with emotion. Their implications, rather than be confined by the limits of the frame, spillover. As critic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas puts it, they’re films that refuse the “cultural tendency towards passive media consumption.”

His films capture some of the human condition’s unruliness. In the theory of beauty and art, his subjects unveil through behavior and appearance, aspects of life we would prefer to hide. Yet, this ugliness, rather than be markers of spiritual vacancy, are more often akin to the brutal horror of Jesus on the cross. It’s only through his characters’ contorted agony (occasionally represented in literal crucifixion imagery) that beauty can emerge. Catholicism plays a big role in his cinema, though it would be a stretch to call him a devoted worshipper. His films feature characters who are true believers, though they rarely find any salvation in religion.

Instead, it’s art that stands in for a spiritual lifeline. Many of his characters are artists, and through art, they search for meaning. Like religion, though, their relationships to their work and identity are fraught. From one of his earliest films, “The Driller Killer,” to his most recent “reflexivity” trilogy (“Pasolini,” “Tommaso” and “Siberia”), Ferrara has a career-spanning fascination with the artist and his work. “The Driller Killer” has recently been added to the Criterion Channel and “Siberia” is currently playing as part of Montreal’s Festival du nouveau cinema’s virtual program.

Ferrara has described his decision to pursue filmmaking by saying it was his “vocation.” More than just a desire or ambition, he discusses his filmmaking practices as a calling. Yet, that spiritual line does little to negate the realities of being a working artist. In an interview with Belgian director, Fabrice Du Welz (“Calvaire”) he explains, “It’s my vocation… it’s my calling. It’s my ability … it’s also my gig. It’s how I support myself and how I support my family and support the people around me.”

In his book, So Much Longing in So Little Space: The Art of Edvard Munch, Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgård grapples with art’s meaning in our lives. In writing about biography and experience, he says, “There is obviously a connection between an artist’s personal experiences and his or her works but it is rather less obvious what this connection consists of.” The danger of writing about a filmmaker like Ferrara is insinuating false connections between the man and his creations. Yet, undeniably, his preoccupation with the tension between art as a tool for salvation and survival comes to the forefront.

Ferrara worked on several short films and even a porno before he made his first mainstream success, “The Driller Killer” in 1979. Made for less than $100,000, “The Driller Killer” is a film about a painter who cracks and goes on a killing spree.

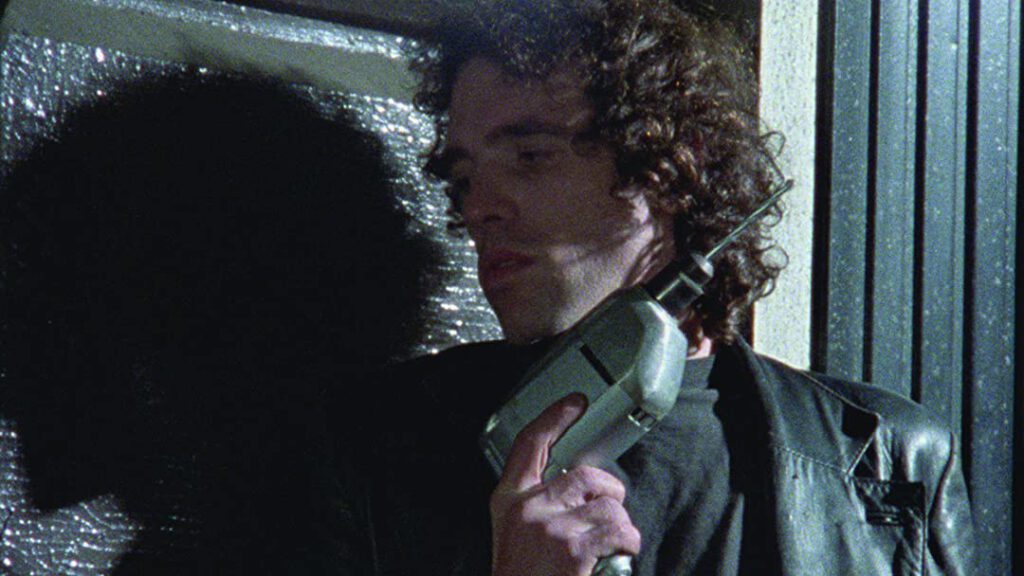

Ferrara often calls the film a kind of documentary that portrays pre-Giuliani New York, particularly the punk scene. The film is about a painter, but it’s also about the punk bands’ rehearsal spaces as they live and work in the city. In the pre-production stages, New York Dolls vocalist David Johansen was even considered for Reno’s lead role. Ferrara stepped in as a matter of practicality, as they were unsure how long production would go on.

“The Driller Killer” was shot at the end of the 1970s and feels like a product of rage. Ferrara often cites “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” as an influence at the time, a film that not only was made on a shoestring budget but also captured the brutality of the era. While both films push respectability boundaries in terms of gore, “The Driller Killer” and “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” differ in the origins of violence.

In Hooper’s film, violence is embedded in the landscape’s fabric and bred into the characters. In a sense, it is beyond their control. In “The Driller Killer,” however, it’s clear that Reno has a choice. In the frenzy of pressure to finish his work of art, he confuses creation and destruction. Reno’s murderous impulses begin as fantasies, and eventually, he acts them out. Yet, time after time, he has the opportunity to stop himself. He chooses not to.

Reno has to finish his painting to pay off his debts and so that he can continue to paint. While art has become his compulsion, as a working-class artist, he needs to sustain his living as well. His need to create becomes a point of desperation, especially as all other aspects of his life, girlfriends, bills and the city itself continually get in the way of his ability to focus on the work at hand. While we feel that he’d be perfectly happy if he could devote his life to painting and painting only, that is an impossibility. The consequence of that limitation emerges as rage and violence.

“The Driller Killer” launched Ferrara’s career and also was a stepping stone in a variety of other films that portray the artist at work. In films like “Dangerous Game” or “The Blackout,” he explores filmmaking and the blurred lines between what is being lived and created. His movies also feature painters, dancers and actors. Art supplies his characters with work and also offer a reflection on how they see and experience the world.

Since 2014, Ferrara has released three interconnected films, “Pasolini,” “Tommaso” and “Siberia,” that critic Neil Bahadur has coined as his “reflexivity” trilogy. The films explore the life, work and dreams of three interconnected characters and their art. Willem Dafoe, a frequent Ferrara collaborator, stars in all three.

With “Pasolini,” Ferrara explores the many facets of Pasolini’s life, including elements of an unfinished movie. Set after his controversial production, “Salo: 120 Days of Sodom,” “Pasolini” showcases an artist who, beyond even the content of his work, offends fascists and the power class merely by existing as a gay Marxist poet. In the film, Pasolini’s mom and sister discourage him from pushing things any further, fearing for his life. Pasolini, though, refuses to stay silent.

“Pasolini” stands out in Ferrara’s filmography as a rare instance where his characters are deified. Pasolini makes the ultimate sacrifice in the name of art and living. His art doesn’t get muddled with rage or chaos like Reno in “The Driller Killer;” it is calculated and pointed. While aware of his continued outspokenness’s potential consequences, he chooses to live according to his own terms. A much different expression of free will than Reno, Pasolini makes the ultimate sacrifice, his life, in order to exist freely as an artist.

“Pasolini” is followed by “Tommaso,” an improvisational film about a film director living in Rome with his new young family. The parallels between this character and Ferrara are apparent, especially as the film co-stars Ferrara’s wife, Cristina Chiriac, and their young daughter. However, both he and Dafoe deny the film’s autobiographical intentions. “Tommaso” is the binding force that connects “Pasolini” and “Siberia,” informing and commenting on both.

In “Tommaso,” the titular character is working on his next film’s pre-production, which is quite clearly “Siberia.” He regularly attends narcotics anonymous meetings, tries to be a good father and husband, and also struggles with rage. Whereas many of his Ferrara’s previous artists were overwhelmed by different aspects of identity bleeding into each other, Tommaso seeks balance and showcases the domestic struggle to work as a filmmaker while also being a man with responsibilities for his family and loved ones. It’s an intimate portrait of a character grappling with age and art.

Unlike Pier Paolo Pasolini, “Tommaso” has chosen to live not just as an artist but also as a man. He has quieted his passions as a means of living up to his responsibilities. He confronts a drunken man on the street in one particular sequence, asking him to shut up so his baby can sleep. We sense the violence rising, Dafoe’s performance channelling an aged Ferrara, lurching quite literally forward as he confronts this man disturbing the peace. It’s a sequence wrought with the tension between brutality and grace. Perhaps sensing a kinship with the man, Tommaso softens, and calmly the situation is resolved. It’s a moment of immense power as a character chooses to forgive and be forgiven.

The film ends on a home video of Ferrara’s daughter dancing. It is a fleeting moment of beauty and a poetic reminder that his sacrifice and choice to be redeemed each morning (for redemption, rather than a lightning strike, is a choice we make day to day) are worthwhile. His love for his daughter gives him hope.

In direct contrast with the almost documentary realism of the film, are brief and hastening sequences of imagination. Tommaso imagines affairs with women, a Jesus-like figure stopped by police and his own crucifixion. Anticipating the dreamlike “Siberia,” we exit the mundane and enter the realm of imagination.

In “Siberia,” Dafoe stars as Clint, a bartender living in the tundra. The film operates in a landscape of uncertainty, with unexpected bursts of violence (including a bear attack). Shot all over the world, each landscape (the tundra, the desert, a cave) invoke primal and sacred locales. It’s a literal search for the artist’s soul and an attempt to reconcile the unseen aspects of self with the physical realm.

The film attempts to capture the landscape of dreams and the realms in which an artist finds inspiration and meaning. Yet, in typical Ferrara fashion, there are no clear revelations. Only in a show-stopping dance sequence, where Dafoe is “liberated” by Del Shannon’s Runaway, do we sense any freedom or direction for the character. As this sequence leads into the film’s third act, the movie becomes a bit more upbeat. Even deeply ingrained in symbolic and primal imagery, Clint’s power lies in his ability to choose how he makes sense of his impulses. He can choose to live the life he wants and take from his imagination and subconscious what he wants. Inspiration is not divine but an aspect of free will.

Watching “The Driller Killer” and “Siberia” back to back evokes a strange experience. In many ways, they don’t feel like they’re made by the same man—perhaps, in a way, they aren’t. Yet, they also very intimately showcase different approaches to the trials of creation. They’re similarly about men grappling with their place in the world and their attempts to make sense of it. Whereas Reno in “The Driller Killer” defaults to rage, his frustration boiling over into violence, there is a more significant move towards acceptance in “Siberia.” The destructive impulses remain, but Clint chooses not to give into them.

Ferrara is one of the most eclectic filmmakers working today. Over his career, he’s explored what it means to be a working artist, from the struggles to pay the bills to the more resonant spiritual qualities of what it means to be a filmmaker. In his work, art becomes a source of anxiety but also of redemption.