1.

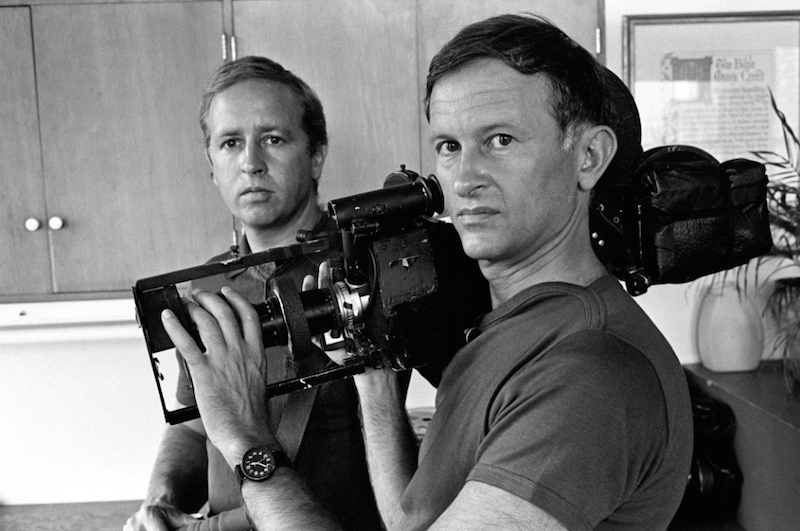

“Albert Maysles, Pioneering Documentarian, Dies at 88“: Anita Gates of The New York Times pens an obituary for the brilliant filmmaker, who died last Thursday. Related: RogerEbert.com Editor In Chief Matt Zoller Seitz’s 2002 Star-Ledger profile of Albert Maysles, and his new piece, 8 things about Albert Maysles. See also: Salon‘s Andrew O’Hehir revisited the Maysles brothers’ masterpiece, “Grey Gardens,” in an excellent essay published on the day of Albert’s death.

“Mr. Maysles (pronounced MAY-zuls) departed from documentary conventions by not interviewing his films’ subjects. As he explained in an interview with The New York Times in 1994, ‘Making a film isn’t finding the answer to a question; it’s trying to capture life as it is.’That immediacy was a hallmark of the Maysles brothers’ films, beginning in the 1960s, when they made several well-regarded documentaries. But it was ‘Gimme Shelter’ (1970), about the Rolling Stones’ 1969 American tour, that brought them widespread attention. It included a scene of a fan being stabbed to death at the group’s concert in Altamont, Calif., and the critical admiration for the film was at least partly countered by concerns that it was exploiting that violence.Concerns about a different kind of exploitation were expressed about ‘Grey Gardens’ (1975), a double portrait of Edith Bouvier and her daughter, Edith Bouvier Beale, both cousins of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who lived in squalor and with what some saw as mental confusion in a once-grand house in East Hampton, N.Y. But the film captured and held the public’s attention for decades, perhaps because the public sensed what Martin Scorsese wrote decades later in a foreword to ‘A Maysles Scrapbook’: ‘When Al is behind the camera, there’s a sensitivity to mood, to space and light, to the energy between the people in the room.’ Mr. Scorsese described Mr. Maysles’s camera as ‘an inquisitive presence, but also a loving presence, an empathetic presence, tuned to the most sensitive emotional vibrations.’”

2.

“What ISIS Really Wants“: The Atlantic‘s Graeme Wood writes an invaluable analysis of the motivations behind The Islamic State’s atrocities.

“We have misunderstood the nature of the Islamic State in at least two ways. First, we tend to see jihadism as monolithic, and to apply the logic of al‑Qaeda to an organization that has decisively eclipsed it. The Islamic State supporters I spoke with still refer to Osama bin Laden as ‘Sheikh Osama,’ a title of honor. But jihadism has evolved since al-Qaeda’s heyday, from about 1998 to 2003, and many jihadists disdain the group’s priorities and current leadership. Bin Laden viewed his terrorism as a prologue to a caliphate he did not expect to see in his lifetime. His organization was flexible, operating as a geographically diffuse network of autonomous cells. The Islamic State, by contrast, requires territory to remain legitimate, and a top-down structure to rule it. (Its bureaucracy is divided into civil and military arms, and its territory into provinces.) We are misled in a second way, by a well-intentioned but dishonest campaign to deny the Islamic State’s medieval religious nature. Peter Bergen, who produced the first interview with bin Laden in 1997, titled his first book Holy War, Inc. in part to acknowledge bin Laden as a creature of the modern secular world. Bin Laden corporatized terror and franchised it out. He requested specific political concessions, such as the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Saudi Arabia. His foot soldiers navigated the modern world confidently. On Mohamed Atta’s last full day of life, he shopped at Walmart and ate dinner at Pizza Hut.”

3.

“Silencing ‘India’s Daughter’“: The New Yorker‘s Andrea DenHoed explores how “a last minute intervention by the Indian government” banned the BBC broadcast of Leslee Udwin’s documentary about the 2012 rape and murder of a young woman on a bus in Delhi.

“The details of the crime are already well known in India. A twenty-three-year-old medical student named Jyothi Singh was walking home from a movie with a male friend at 8:30 P.M. A group of men who had been out drinking picked them up in a privately owned bus, and asked them what they were doing out so late. The men beat Jyothi’s friend and took Jyothi to the back of the bus to rape her. The details of the attack, from which Jyothi was left beaten, bitten, and disembowelled, are truly gruesome. She was somehow still alive when the men left her and her friend on the side of the road, but she died of her injuries several days later. At the center of Udwin’s film is a series of interviews with the man who was driving the bus that night, Mukesh Singh. He is one of four men currently on death row for the crime. (A fifth man was sentenced to death but committed suicide in prison; a sixth, who is underage, is serving a three-year sentence.) His clear-eyed, unaffected demeanor as he recalls that night, as well as the ease with which he justifies what happened, adds another dimension to Jyothi’s story. ‘A decent girl won’t roam around at nine o’clock at night,’ he says. ‘A girl is far more responsible for rape than a boy.’ Her death, he says, wouldn’t have happened if she hadn’t fought back. He doesn’t seem repentant, but he doesn’t seem to be burning with misogynistic rage either. (It might be easier to process his statements if he were.) If anything, he seems annoyed—unable to understand why this particular rape has caused so much consternation.”

4.

“Harrison Ford plane crash stirs subconscious fears“: Steven Zeitchik of The Los Angeles Times dissects the repercussions of the iconic actor’s much-publicized crash.

“There’s reason to be skittish. We’d been in related circumstances over the years too many times with beloved figures (Ritchie Valens, John F. Kennedy Jr., James Dean and, just a few weeks ago, Bob Simon, to name only a few). When reports like this begin to circulate–increasingly fast in the insta-medical reporting of the TMZ age–the full picture often bears out some of our worst fears. There is, with these accidents, the sheer caprice factor. A celebrity brought low by addiction or depression is a hugely tragic story, but there is often a responsibility calculus that follows as we seek to determine what system or which people failed them. A transportation accident seems random, or at the very least a highly disproportionate consequence for something as fickle as weather or a failed engine. When it involves any machine that flies, there is an even more particular iconography. The private plane is a symbol of privilege, and while for a few ornery types that can cause a limiting of sympathies (there were a few, but blissfully only a few, such figures on social media Thursday), for most of us it has a more ominous ring. By its intimate nature, the private plane suggests a singling out of just a few people for tragedy. (That it’s a means of transport used only by very successful types may underscore this point, almost as though by someone being endangered in the very thing that represents their success an especially perverse form of karma is at work.)”

5.

“Outside Man“: Jesse Katz of The California Sunday Magazine profiles Scott Budnick, producer of “The Hangover” and dedicated advocate for prison reform.

“If Budnick were a priest or a lawyer, even a counselor or a coach, these jailhouse pilgrimages would be easier to explain—his declarations not so incongruous. But until a bit more than a year ago, Budnick had a day job as a Hollywood producer, and not one devoted to bringing socially conscious, inspirational tales to the screen. As the number two at Green Hat Films, Budnick executive-produced the raunchy, uproarious ‘Hangover’ movies, the top-grossing R-rated comedy franchise in history. For years it meant living a kind of double life, racing from the Warner Bros. lot in Burbank to Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall in Sylmar, interrupting conference calls to accept collect calls, burning through girlfriends once they realized he would rather be, as his official bio says, ‘walking the tiers of California jails and prisons on his nights and weekends’ than a red carpet. ‘These kids,’ Budnick says, ‘are what give me life.’ At once earnest and hyperbolic, loyal and schmoozy, Budnick can come across as a character in one of his own films. When people first meet him, whether it be an inmate or a warden, a politician or a philanthropist, the initial reaction is almost always the same: ‘Who the f—k are you and what are you about?’ his longtime mentor, Javier Stauring, who oversees the L.A. Archdiocese’s youth-detention ministry, says with a laugh. Budnick is not the likeliest crusader, in other words, to be redefining how California punishes and redeems.”

Image of the Day

“Actress Patricia Morison reminisces as 100th birthday nears” in an interview with Susan King at The Los Angeles Times (photo by Katie Falkenberg).

Video of the Day

A brief yet priceless interview excerpt with Albert Maysles, courtesy of AFI’s SILVERDOCS.