Nicolas Winding Refn, the director of “Only God Forgives” and the king of stylish wound-infliction cinema, recently said he’s never experienced violence at all, that it terrified him beyond the telling, and that he’d fall to his knees and do what it took to stop it from happening to him. “I would just give them what they want: ‘Please don’t hurt me! Please, no!’”

When I read that, I thought of how one of the very first things I knew of this world was being five or six and in a flurry of action being violently hurt and left to weep in a dark room as I learned life’s first big lesson: that waiting for violence is as bad as having it inflicted. Hitchcock, of course, based his entire career on the same terrible dynamic. (For obvious reasons, I’m omitting names.)

Five years later, a relative who was not only epileptic but severely mentally ill drove the car into a crowded intersection; I can still replay the millisecond-long body slam impact of metal impacted by metal, my body for a forever-second hurled up to the cabin’s ceiling, then flung against the padded door shoulder-first, face following.

Fast forward, junior high, first day. I got it in my fool head to wear the tight purple flares and paisley shirt like I’d seen John Lennon wear on the sleeve for the “Lady Madonna” single. At lunch a plug-shaped boy hurled me to the cement and beat my head until my ears leaked blood, screaming “f#@king faggot!” like it was a song request. For three years plug-boy and his acolytes bullied me, finally realizing that my mint copy of Robert Shekley’s “Dimension of Miracles” was my only prized property and, right there in Plastics Class, ripping it from my hands, slapping me, and tearing the cover and causing me to finally have the PTSD nervous breakdown I’d been working on since I was six.

I wept, openly, the worst thing a boy can do, of course. The smartest thing was to find an easy-access hiding place where nobody could pulp your head, make your day terrifying, or ruin your sacred books, which meant The Pacific Theater.

The Pacific showed a constantly-rotating triple bill of whatever was around: Ingmar Bergman, John Cassevetes, Jose Franco, “Logan's Run,” “Cries & Whispers,” “Macon County Line.” Throw in coming attractions and intermissions, that one ticket equaled six hours of in-the-dark safety. I believe that more people than we’ll ever know joined the sacred order of the cineaste for the simple reason of needing shelter from a variety of monsters. Guillermo del Toro, for one, became our king of maker of monsters, at least in part as a way of mastering the abuse battlefield that was his childhood. I just know that more hard years passed before easier years showed up.

I remember leaving a screening of “Patton” in such a state of naked terror that I considered strangling myself—not because I wanted to hurt myself, but because my anxiety was so terrible, my heart pounding so violently, my skin seemingly on fire, my vision blurred, that it just seemed reasonable to cut down my oxygen so I would just fall asleep so that when I woke up, the panic would have passed. In retrospect, my terror was based on George C. Scott’s mega-macho resemblance to one of my abusers.

I didn’t invite anyone to the movies with me. Ever.

Problem is, the movies, especially American movies, are false about violence, because so much of the American dream is based on men who need to act out a self-destructive masculinity that can only express experience and need through violence, because violence is quicker than sex and so violence is better as commerce and so violence must be made as delicious and American as possible for boys and men.

Unfortunately, I’d get adult confirmation on these early observations when a bus ran a light and hit me in the face and then later, at the age of 36, when a skinhead in New York’s East Village, apropos of nothing, beat the crap out of me.

You wonder if early violence leaves a scarlet letter on people. If you’re a survivor, please listen: this is not true. It. Just. Isn’t.

Anyway, violence, the movies, lies. The movies do not tell you that (1) most of the time it’s over before you know it happened, (2) that both victim and perp go into a visually uninteresting altered state, a sort of adrenalized dizziness—and if you’re young, a certain uselessness, (3) that muscle cramps and pain and other symptoms just get worse, not better, and that with injury comes swelling and infection, (4) that the strongest men weep, and (5) that nobody ever completely recovers from even the smallest violent act against another human.

The first true thing I learned as a boy: the vic isolates. I never asked a single person to see a single film until I was maybe sixteen, and then other people were asked and I followed, unsure to the theater: as the Was (Not Was) sang, like a spy in the house of love.

Violence-created solitude means you never know there are people helping you. One of the many great things about Jane Campion’s TV series “Top of the Lake” is the way it shows how violence has infected everyone, virus-like, in a small New Zealand village, each according to their vulnerabilities. In the case of the cop played by Elizabeth Moss, it caused her to live under an invisible nimbus of isolation and anxiety. I saw her and saw preadolescent me: always checking after speaking for possible danger signs, avoiding eye contact, and keeping to herself, because really, why chance otherwise?

I finally entered high school with enough anger and outlier pals to help me not get physically injured. I got a guitar, and the first song I learned to play, loved playing, got a rush from playing in that special way when something finally represents a basic truth of the world you know, was Mott the Hoople’s “Violence”, whose chorus goes:

“Violence

violence

it’s the only thing

that’ll make you see sense”

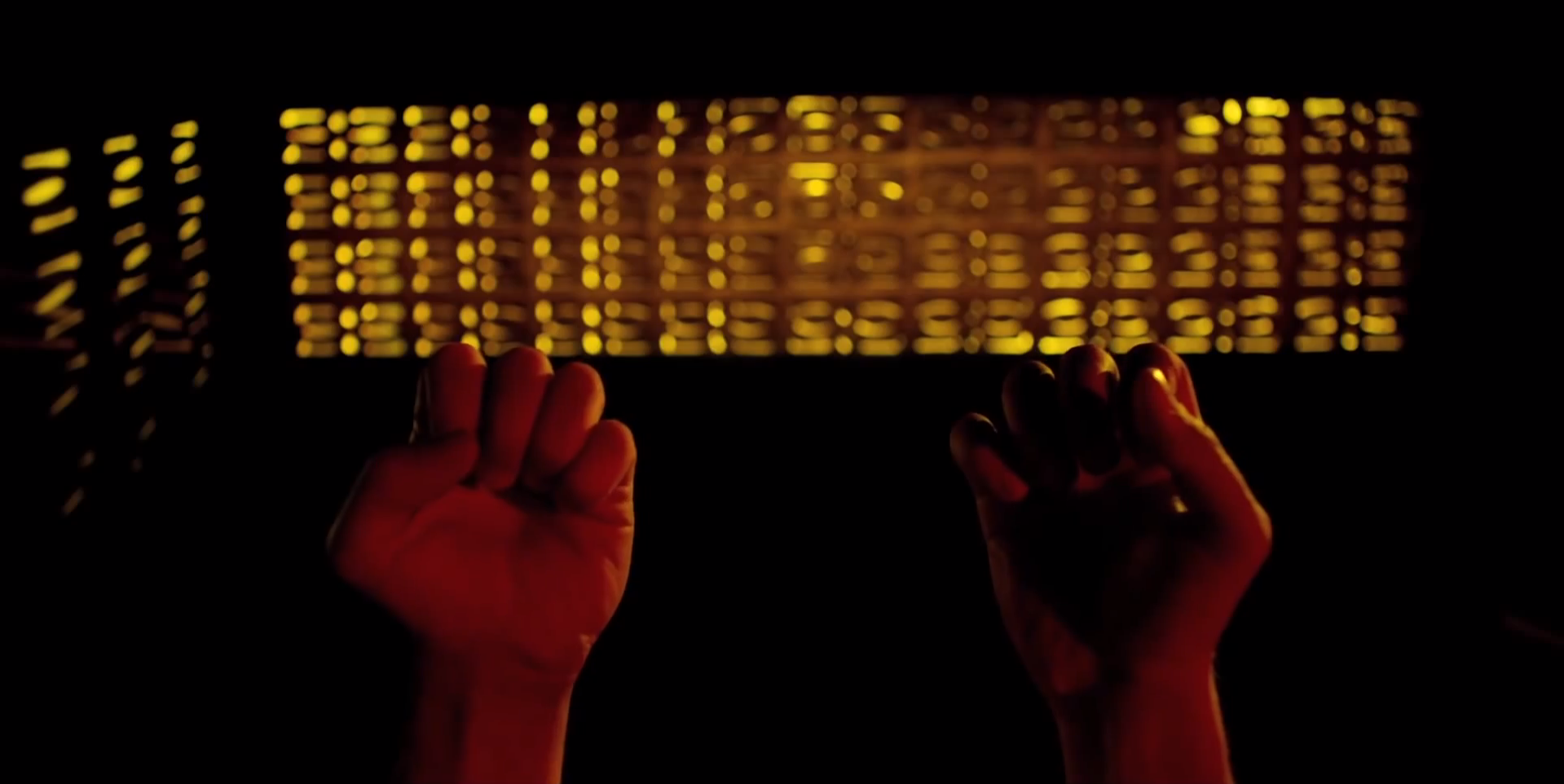

When I watched Refn’s “Drive“—an overwhelming accruement of currently hip stuff, of kitsch fashion, purring EDM, cuddly sociopaths, dreamy gamines, muscle cars, murdered T&A, a guy’s head pulped, seeping wounds, whatever—the process of negotiation I engage with when dealing with all violent fare went into Def Con 2 all the way to disassociation mode. It’s an old, self-protection program, subroutine of how I learned long ago to deal with violent films so that I still feel safe.

Cartoon violence is no big deal for me. Superhero films, monster movies, non-female-hate horror, “Fast/Furious” cartoon action—no problem. Misogyny horror, Cheney-era torture thrills (see Abrams, JJ, career of), post-Tarantino hipster kill-spree films: not so easy.

My reaction to these films can range from a sense of being slimed, to free-floating anxiety, to despair, to—before my bipolar disorder was stabilized six years ago—generating suicidal ideas.

And yet really, really, incredibly disturbing violent films like “Spring Breakers” and Refn’s own “Valhalla Rising”? Harder for me to process. Harder for me to watch without being triggered into those dark places. But worth that extra work, because they contextualize their violence with the only 100% true truth of violence: it makes both perp and victim smaller, less human, lost.

Refn’s new hyper-violent films have worked as a lead-up to a new flattening of audience affect that finds expression in “The Following”—the most human-life-hating TV show in the medium’s existence. The zombie flood—at heart Darwinism, with viewers winners of the mean new evolution, and everyone in town meaty targets—never ends. Even “Prometheus,” operating in an science fiction genre usually informed by optimism, cynically offered pop-up-target characters we cared nothing about, so as to to feed its meat grinder plot.

In order to engage in this literal degradation of human value via cinema, TV or Netflix, parts of my brain have to tell other parts of my brain, “Okay, I’m not going to let this upset me. I’m not going to panic. I’m a grown man.” But it does upset me. Art is supposed to increase us, not make us bargain with the agents of diminishment to get through a couple hours of calamity.

And while there’s no denying the fact that the balletic blood tragedies of Peckinpah, the filthy death crescendo of “Taxi Driver,” and Paul W.S. Anderson’s entire oeuvre of violent Pop Art humanism make us more than were before we enjoyed them, I am also, always, forever in touch with the tremulous boy who lived for in fear of the other shoe dropping.

I don’t have a grand thesis here. I can only tell you that most of the time, in screenings, when talking with my peers, I feel like a war vet among good people, talking about something I believe that I can contribute but not knowing exactly how to do it.

Maybe this piece is me trying to find ways to change that.

You’re my good people. I want to hear you talk about this.

How does screen violence make you feel? If you’ve experienced real violence, what kind of movie violence is acceptable to you? What kind hurts, and what kind doesn’t?

What goes through your mind when you see that blood on the screen?