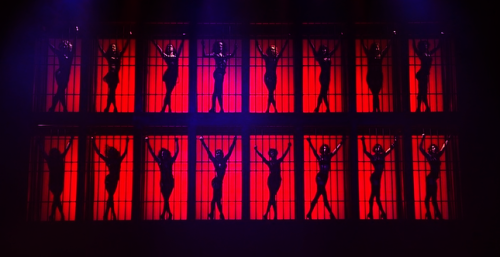

The women behind the murderesses of the Cook County Jail are both strikingly nondescript and yet embody an easily recognizable archetype. Almost costumes of femininity, exaggerated like a drag queen, a siren-like light illuminating them from behind, outlining the bars behind which they stand and pose, these ladies’ aesthetics of gender are heightened despite the fact that they have no name, no face, and beyond the blackness of the outline, no identity. During the “Cell Block Tango,” they are there to intensify the sensuality of the primary women in the number, whose dysfunctional and abusive relationships are performed and rewritten as vaudeville dance and striptease. Their heels are ludicrously large, and there’s an implication of nudity, clearly suggesting that these light fixtures in the background of this musical number in Rob Marshall‘s “Chicago” are movie musical versions of window prostitution, articulating an uneasy relationship that the film itself has with its women; that its women, and their lives, occupy a complex and fraught relationship in a broader society, as they do outside of the film. And we queers, especially queer men, love a complicated, “difficult” woman. We are hungry for them, to consume them. Maybe, in these paradoxically flat yet fluid images, we can identify with them too. These outlines offer space in the darkness to play with our own identities.

That friction is amplified by a queerness within the film, and otherness in the characters, a sidestepping of traditional and heteronormative values and instinctual trust in socially dominant ideas of production and reproduction, or sex and the continuation of family lines: Roxie Hart (Renee Zellweger) and Velma Kelly (Catherine Zeta-Jones), as do the other women of the “Cell Block Tango,” do away with their spouses and partners, intent on self-fulfillment no longer based on marriage or making a family. And both, not so much different sides of the same coin so much as pairs, or dyads, in visual and aesthetic approaches to the same goal (fame, spectacle, performance), become instantly recognizable within the world of the film. Their image and persona become what we are buying and selling, in our seats and out in the world. This seems to be particularly of interest in a queer cinematic history in that their persona, the language of why they are famous in the first place, is an avoidance of heterosexual dynamics that are created from social pressure and expectation. But as compelling as Roxie’s blonde kewpie pie looks are (certainly director Rob Marshall’s own adaptation of blonde starlet looks, not so far off from Fay Wray), turning to Zeta-Jones’ Velma finds fertile ground for queer identification. No, dis-identification.

And what are we looking at when we just look at these silhouettes? Not the person, certainly; an idea, a construction that’s also natural, a shadow that somehow shimmers with substance. You can reach out to a silhouette and only grab what’s most elemental, like a trick of the light that continues to seduce. When queerness is introduced to shadows, a space that queer people themselves have found a home in, they find power in what José Esteban Muñoz calls “disidentifcation,” meaning “to read oneself and one’s own life narrative in a moment, object, or subject that is not culturally coded to ‘connect.’” We dare to question them, but shadows are unanswerable, and queer people will fill in those blanks to find parts of themselves. With certain performers, like Catherine Zeta-Jones, Marlene Dietrich, and Liza Minnelli, their shadows melt into something more illusory and complex; they become a triad of duplicity that has become its own visual grammar within gay and queer culture.

Velma’s severe bob, as precise and sharp as her dancing, nods to Louise Brooks’ Earth-shattering naughtiness—a siren ringing the alarm bell for timeless sexual power, transcending the era of film in which she left a scalding burn—and Zeta-Jones’ embrace of the costume creates its own self-aware wink. At the beginning of “And All That Jazz,” the platform raises her, the blue light and white flame of the spotlight creating shadows around her body, outlining not only Velma the performer (now alone, her sister gone), but Velma the nightclub act in dialogue with Brooks. She wears a flapper dress to establish her own theatrical and performative presence (as well as independence), and that murder becomes an added element to the persona of Velma Kelly as public figure, so do the parallels between her silhouette as itself an extension of her persona and its relationship to Brooks in a film like “Pandora’s Box,” another story (with Sapphic flavors) of a woman subverting and transgressing her role, the bob adding androgyny and ambiguity that is especially accentuated when reduced to its most elemental features and flattened in silhouette. In short, the bob in silhouette makes Velma’s (and Louise’s) gender walk a fine line between what we understand as male and female, aesthetically. And yet, in the aftermath of “Chicago”’s original release, Zeta-Jones as Velma has become iconic, on its own terms as well as itself paying homage to an older performance. (And it’s clear also given that “Chicago” is both an adaptation and a remix of Fosse.)

Silhouettes become a trick and illusion, perhaps outlining the way gender is imitated and yet impermanent as a form of public (and personal) performance. Gender might be fundamentally misleading, and the performances we practice to ensure its stability, that our understanding and grasp of gender does not change, are the most deceitful trick of all. How else would Marlene Dietrich—a halo of smoke around her top hat, with Josef von Sternberg striking a key light so that the light and the dark both harden the borders of her cheekbones and jawline and yet ironically mystify her gender and her identity—be the most immaculate of tricksters? In von Sternberg’s “Morocco,” as Amy Jolly (another club singer), she smirks with a cigarette whose length is a tease. Who she is as an image and myth of an actor, how we know her, is undermined by the lights and by the silhouette, making the physical body (as it is supposed to tell “the truth” about itself, including her gender) less stable by its cleanest, most uncomplicated form, the lies that the body telling less elaborate yet bigger in scale. Dietrich’s legacy is hinged upon a lack of clarity, a smokiness that begs for illusion and its artifice to be sustained, even in its instability.

But while Dietrich relies on that instability as the foundation of her persona, the failure of that balancing act becomes a language of iconography on its own terms, becoming fundamental to a queer cultural vocabulary. That very failure, and perhaps lack of self-awareness, is key to another form of relating to characters for queer people (men especially), with a comfort in failure in fiction and failure in a real world. That appears to be the case with Sally Bowles (Liza Minnelli) in Bob Fosse’s “Cabaret,” who, despite a decade or so after “the events” of “Chicago,” also adopts a similar personal aesthetic as Velma’s. But Sally’s search for stardom is consistently interrupted by her own follies and mistakes herself as some kind of greatest roadblock. The joke of Bob Fosse’s “Cabaret” is an irony, the sensibility itself often connected to queer aesthetics, and an meta joke of Minnelli’s own actual talent in opposition to Sally’s supposed skills, and then Minnelli’s star family tree. That she’s talented and is unable to escape the rise of fascism, which has been permissible so long as it doesn’t affect her, is its own kind of tragedy.

When we see the side of her face up close in profile during “Maybe This Time,” the light’s diffuse, she wants this (some confident relationship) as much as she wants “this,” the audience’s gaze and attention, that she’s captured by performing both kinds of wanting. She holds us on a string, the in-movie audience and the real world one, a funhouse mirror of desire and persona, that, when flattened by profile and silhouette (which is referenced in the title number at the end of the film, as we see her looking deep into the blazing spotlight), who are we to know if she’s actually famous? She’s not famous and she’s famous at once, she’s Liza Minnelli with the intricate Hollywood backstory and she’s Sally Bowles, a nobody who craves that (self-)mythology.

The image of Liza as Sally Bowles, even in silhouette or outline, bending around a chair, bowler hat perched like a peekaboo joke on her head, in “Mein Herr,” or in faux-flapper garb in “Money, Money,” joins with Zeta-Jones as Velma Kelly and Dietrich as Amy Jolly as silhouettes that are magic tricks, both by the characters they’re playing and the gay and queer audiences engaging with them, entranced by their lies and deception. That very instability of identity is the base on which drag is built, both as exaggeration and excess as well as subtle reduction. That these films take place within an environment or context where fame and celebrity do exist suggests a dizzying infinity mirror or Russian doll of identity and celebrity, a self-reflexivity that the image of their image has become an artifact of iconography, an awareness of the artifice becoming viral commodity. The point is, these people, these women, these performers as silhouettes, aren’t there; nothing about them is fixed in place or permanent, especially not how we interact with their gender or their identity, except their spell. They’re the smoke unfurling from a cigarette. If you grab it, it’s gone.