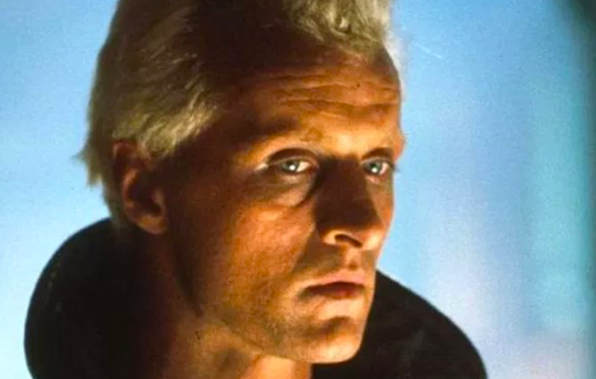

How fitting that Rutger Hauer‘s greatest screen moment, the scene that every obituary writer is inevitably leading with, was cowritten by Rutger Hauer himself: the death of “Blade Runner” antihero Roy Batty on a rainy rooftop at the end of Ridley Scott’s 1982 classic. As Vangelis’ synth score rises to a peak of euphoric lament, Batty tells Harrison Ford’s emotionally burned out robot-killer that he carries memories of wonders that the other man can barely imagine, then wistfully adds that “all those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.” It’s a moment so powerful that it merits its own Wikipedia entry, separate from the movie that contains it: “Roy Batty’s soliloquy,” or “The C-Beams speech.”

From his early breakthrough years in in Dutch films by one of his most important collaborators, director Paul Verhoeven, through his more recent period as an oddball elder statesman who could be menacing or sweet depending on the requirements of the project, Hauer seemed to gravitate toward parts that subverted expectations and rattled viewers, making them reckon with their sympathies and ask where they originated: in the character himself? The story? The casting? The way he was clothed and lit and photographed? And underneath all that was a procedural question: what would it take to make you like a bad person, or distrust a good one? Like Warren Beatty’s McCabe in “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” the actor had poetry in his soul, and it came out at the damnedest moments. He was an example of a specific and rare type of screen actor, one with leading-man looks and charisma but a grindhouse or B-movie star’s fascination with violence and sleaze, instability and mystery, and the dexterity and versatility of a skilled character actor (though his magnificent face, like a Roman bust of a revered general or philosopher, was so striking that you could never really disguise it—not that most directors would’ve wanted to).

He was Roy Batty, always and forever. But he was also a terrific straight-up bad guy. He was cultivated, intellectual, and frightening as the terrorist battling Sylvester Stallone and Billy Dee Williams’ blue collar New York cops in 1981’s “Nighthawks.” He played the title character in Robert Harmon’s 1986 horror thriller “The Hitcher,” combining a smirking devilish playfulness with the ghoulish destructiveness of the original Terminator and the supernatural stalkers who cut bloody swaths through the slasher pictures of the 1970s and ’80s. (In retrospect, the character feels like an ancestor of Heath Ledger’s Joker.) That same year, Hauer starred as bounty hunter Josh Randall in a film version of “Wanted: Dead or Alive,” based on a TV series that made an international star of Steve McQueen, but it was a much harder-edged version of the character, in line with the “bad” good guys who had become a cliche in 1980s R-rated action movies.

Hauer could be a marvelous old-fashioned leading man when circumstances allowed it, as in “Ladyhawke,” a film whose central dramatic conflict bordered on a romantic comedy predicament: Hauer’s knight was a wolf by moonlight, but his great love (Michelle Pfeiffer) was a hawk by day, which meant they were cursed to be together yet always apart. (Tears in rain, a love story.)

But it was more common to see Hauer cast as somebody like Martin, the mercenary he played for his greatest collaborator, director Paul Verhoeven, in the 14th century adventure “Flesh + Blood.” This is a man who presents as a dashing macho rascal, in the mode of a Burt Lancaster or Kirk Douglas action hero from earlier decades, yet is crueler and more nihilistic than any of them, looting and raping his way through the countryside with his band of greedy, violent men. The movie’s leading lady, Jennifer Jason Leigh, is established in Verhoeven’s sicko equivalent of a Hollywood “meet cute,” a gang rape that Martin stops only so that he can continue the job solo. Yet by the end of the film, even after the heroine has brained Martin to stop him from killing her nice boyfriend Steven (Tom Burlinson), she lets him escape the movie’s final setpiece without comment. Rape is a constant in Verhoeven’s movies: the director’s 1980 youth drama “Spetters,” about Rotterdam dirt bike racers, includes a lengthy scene where the hero is sodomized by a group led by Hauer’s character.

It’s a testament to Hauer’s innate likability that International audiences were able to watch him in scenes like that—or as Hitler’s architect Albert Speer in the 1982 miniseries “Inside the Third Reich,” or in the grisly centerpiece of “The Hitcher,” in which a character (Leigh again, oddly) is torn in half by Hauer’s villain—and then accept him in other films as a nice guy, or at the very least, as somebody who wasn’t all good or all bad, just complicated, often a victim of circumstance battling his conditioning, as in Verhoeven’s “Soldier of Orange,” the film that made Hollywood take notice of Hauer, about a group of friends who all deal with the German occupation in different ways, by resisting, collaborating, or enthusiastically joining in.

There were times when the writing failed him, or where he seemed miscast, or both—as in the original film version of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” where he seems to have been hired as the vampire Lord Lothos for his fantasy bona fides but more egged on than properly directed; and Nicolas Roeg’s drama “Eureka,” where his character is slimy, opportunistic and weak, yet Hauer is so naturally charismatic that it’s hard to believe he could be completely dominated by Gene Hackman’s hero, a gold magnate. When he was cast in the sort of role you’d never seen him in—as in Ermanno Olmi’s Italian production “The Legend of the Holy Drinker,” where he played a homeless alcoholic and petty criminal—you could feel him becoming invigorated and rising to the challenge.

Few of Hauer’s later roles had the impact of his early work, though in looking over his filmography, this seems less his fault than that of an industry that couldn’t figure out what to do with him, other than typecast him or shoehorn him into roles that needed some sort of a “name,” whether or not his was the right one. He was solid in historical TV productions, particularly ones with a World War II focus, like “Escape from Sobibor” (as the mastermind of a concentration camp escape); in genre television like “Merlin,” “The 10th Kingdom,” “The Last Kingdom,” and the 2004 version of Stephen King’s “Salem’s Lot” (as Kurt Barlow, the king of the vampires—a Batty character in more ways than one); and in the self-conscious B-picture “Hobo with a Shotgun” (a better poster than movie) and “Dario Argento’s Dracula 3-D” (as Van Helsing). He was chilling as an assassin in “Confessions of a Dangerous Mind” and skin-crawlingly evil as a conniving, murderous cardinal in “Sin City” (2005).

But as he aged out of leading man roles, he often seemed more satisfied as an offscreen activist for environmental and his AIDS charity Rutger Hauer Starfish Association, which is partly funded by proceeds from his 2007 autobiography All Those Moments: Stories of Heroes, Villains, Replicants, and Blade Runners. He is survived by his wife Ineke ten Cate, whom he married in 1985 after being together for 17 years; their daughter, actress Ayesha Hauer, and his grandson Leandro Maeder.