With this Sunday marking the 50th anniversary of the release of Arthur Penn’s “Bonnie and Clyde,” we asked our writers to look back on the legacy of the film and Roger Ebert’s famous writing about it.

BRIAN TALLERICO

I often wonder if Roger knew we’d still be reading his review of “Bonnie and Clyde,” one of the most famous of his career. Did he know he had something special? Did he know he had written something that would still be analyzed and considered a half-century later? Like the film, he created something both of the moment, encouraging people to see what he considered a masterpiece, but also something that remains relevant and urgent five decades later. And he was only 25 when he wrote it.

As you might imagine, I often find myself going back to some of Roger’s best reviews, noting how delicately he could balance a conversational turn of phrase with deeply intellectual insight, and “Bonnie and Clyde” remains a timeless piece of film criticism. Much has been written about how much Roger served as a tastemaker, often sensing changes in the industry before writers or even filmmakers saw them coming, but what I find still remarkable about his writing on “Bonnie and Clyde” is how much it reads like something that could be published today. There’s nothing that feels five-decades-old about it. In that sense it is both a piece of criticism that speaks very much to the culture of 1967 and the timelessness of why we go to the movies at the same time. Movies still “do not very often reflect the full range of human life.” And when Roger writes about the “curiously bloodless quality” of American movies of 1967, it’s not hard to think about how much the PG-13 summer blockbuster still retains that tone. His final line speaks to something that I think we all look for in cinema—a duality that is both current and timeless. “The fact that the story is set 35 years ago doesn’t mean a thing. It had to be set sometime. But it was made now and it’s about us.”

BOB CALHOUN

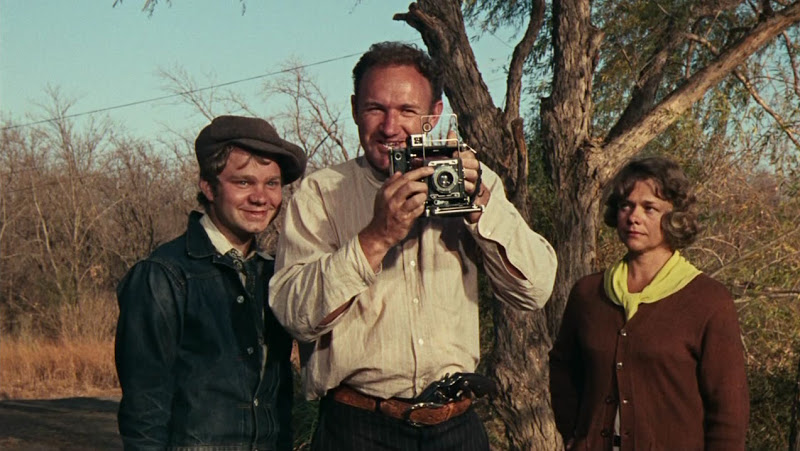

The real Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow were hard-looking people from hard times. They were the stuff of Dorethea Lange photographs. You can almost see the grit from the Dust Bowl in the lines of Parker and Barrow’s faces. They did not look like Faye Dunnaway and Warren Beatty, who have the sheen of nights slept on 1,000 thread-count sheets, manicures and modern dentistry about them.

Arthur Penn’s film “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967), which is now 50 years old just like the Summer of Love, is ultimately more about the time when it was made than the era of its subject matter. This is true of all movies we call period pieces. With “Bonnie and Clyde,” Penn took hardened criminals from the 1930s and refashioned them into rebel icons for the youth movements springing up in Berkeley, the Haight-Ashbury, and the Sunset Strip.

Roger Ebert was keen to this when he first reviewed the film in 1967. “The fact that the story is set 35 years ago doesn’t mean a thing,” he wrote. “It had to be set sometime. But it was made now and it’s about us.”

But there are still aspects of the 1930s that the film gets right. Most of this comes from the film’s supporting cast. Estelle Parsons and Gene Hackman both look like they had done a day’s work in their lives, although things were probably a bit easier on them than if they’d been born 30 years earlier. And then there’s Dub Taylor, who starred in a slew of quickie Westerns in the 1940s, which were often as grueling and dangerous to make as actually being in the Old West itself. Much of the film’s rougher-hewn supporting cast forms a Greek chorus, giving America’s present warnings from its past.

“You best keep runnin’ Clyde Barrow, and you know it,” Bonnie’s mother (Mabel Cavitt) tells Beatty’s Clyde Barrow. She could have just as easily been warning Patty Hearst or Bill Ayers, albeit with much less of a drawl. It’s as if Penn knew where the 1960s would take us by the 1970s, although his film’s popularity could have had a hand in causing the subsequent reality of the Weather Underground and the SLA.

The film’s bloody ending, seen as groundbreaking cinema in 1967, mirrored the gruesomeness of the newspaper reporting of Bonnie and Clyde’s death near Sailes, Louisiana on May 23, 1934 in what the Associated Press called a “barrage of fire.” Shortly after the last bullet was poured into Bonnie and Clyde’s sedan by a posse of police and Texas Rangers, “hundreds of people from the countryside swarmed to the scene to see the end of two of America’s most hunted criminals” according to the Associated Press.

“Bonnie Parker’s head was almost shot off, and it just dangled,” John Abney, described as “a citizen of Gibsland, eight miles from the scene of the killings,” told the AP. “Barrow was badly shot up. There must have been 15 or 20 bullet holes in the windshield of the car. The sides of the car were just peppered full of holes.”

“So thorough was the riddling of the bandit and his woman companion that portions of their flesh was buried in the sides and back of their car,” an uncredited AP staffer wrote, filling in the gore left out of Abney’s account for Americans sipping their morning cup of coffee before heading to work.

“It is intended, horrifyingly, as entertainment,” Roger wrote in his review of “Bonnie and Clyde” in 1967, but it always was. Penn, with all his squibs and their well-timed bursts of crimson, was just reminding a more middle-class America of this.

B.J. BETHEL

Everyone loves shootout flicks. There aren’t many exceptions. A friend of mine is a major gun control advocate. When I told him I had recorded John Woo’s “The Killer,” he quickly rambled off how many rounds were fictionally fired on-screen, and could barely contain himself from dropping a truckload of spoilers. Of course, he loved “Bonnie and Clyde.”

I was struck most by “Bonnie and Clyde” because of its quirky humor, but the violence is what put some of the older guard of audiences off in the late ‘60s. Its take on the movie shootout is just another innovation of the film. It’s fun and games until the bank manager jumps on the side rail of the Barrow’s Ford Coupe and takes one directly to the face, and we’re treated to a sight new to celluloid at the time—blood gushing from the face, those dead eyes staring back, the bank manager lingering on the side of the car for a few moments, just as the camera lingers on him. There’s nowhere for the viewer to hide. There’s more to come, especially the rapid and violent end for Bonnie and Clyde on a dirt road.

Watching Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway littered with rounds, the scene has been rehashed in countless movies, no better than Quintin Tarantino’ s fully-automatic liquification of Hitler by Eli Roth in “Inglorious Basterds.” Sam Peckinpah picked up where Arthur Penn left off with “The Wild Bunch” two years later, upping the blood in a usually family friendly genre like the Western.

Peckinpah and Penn both used a technique pioneered by a Polish filmmaker in the ‘50s, taking condoms and filling them with fake blood, and putting them on actors, to explode when the gun shots rang. Instant gore and blood. It was a shock in “Bonnie and Clyde.” By the time John McClane, from under the conference table, blows off Franco’s kneecaps 20 years later in “Die Hard” with his Beretta 9-millimeter, it’s a thrill.

Bonnie and Clyde’s demise wasn’t so simple as the end of shootout flicks that came later—it was a counterculture statement, much like the end of “Easy Rider,” where Captain America and company are gunned down or beaten to death in a senseless fashion. Years later, Hunter Thompson would write about the wave of the ’60s and its futility cresting and washing away outside his hotel window in Vegas, but Arthur Penn and Warren Beatty put it to film years earlier with the help of the Thompson machine gun.

SASHA KOHAN

I’m a sucker for stories of disaffected youth. Characters who feel out of place, alone and disconnected for inexplicable reasons are close to my heart, which is why products of the late sixties and early seventies feel perpetually true to me. Though the golden folk singers of the era and movies like “The Graduate” and “Harold and Maude” were hugely influential in my upbringing, “Bonnie and Clyde” was my first formal introduction to the sad sixties of cinema—New Hollywood, the American New Wave, the ultimate genre of disillusionment and moral ambiguity for a generation angered by the institutional failures of the one that came before them. It’s meaningful to me, too, that the release of “Bonnie and Clyde” is closely entwined with the rise of two of the most important film writers in American history: Roger Ebert, who had only been writing for the Chicago-Sun Times for six months when his review of the movie came out; and Pauline Kael, whose epic essay of almost 10,000 words paved the way for her prominent career at The New Yorker. When the movie was screened for one of my early undergrad courses, “Writing About Film,” I fell immediately in love with everything about it—including the reviews from these two writers.

Criticism often moves me, in the same way some songs and books and movies do, when I discover that someone else seems to know me, my thoughts and my feelings, better than I do. It was amazing to me that someone as characteristically concise and sharp as Roger (it feels too formal to refer to him as ‘Ebert’) could write something that felt as intensely thoughtful as Kael’s lengthy exploration of the Bonnie and Clyde mythology, and, conversely, that something as broad and historically-based as Kael’s essay could somehow feel as pointedly clear as Roger’s unassuming review. I felt like more of a Kael, myself—succinctness is not one of my strengths—so it was encouraging to see someone dig so deeply into her thoughts on a film with little regard for space or audience expectations, but it truly was seeing this movie and reading these pieces afterward that sparked my profound respect for film writing, and pushed me to consider how critical analysis could be a creative art form of its own.

What I mainly see in “Bonnie and Clyde” now, as opposed to those few years ago (when I was a slightly less disaffected youth), is the couple’s genuine conviction that they’re just regular folks. Bonnie is shocked when the Texas ranger spits in her face; why would anyone want to hurt them, they wonder? When Clyde is suddenly attacked from behind while (courteously) robbing a grocery store, his bewilderment is a little heartbreaking. “Why’d he try to kill me? I didn’t want to hurt him,” he tells Bonnie in sincere confusion. “I ain’t against him.” Bonnie and Clyde aren’t against anyone, actually, except “the law,” an anonymous blob of authority figures, including the banks that take homes away from impoverished families. They don’t relish in killing others. They don’t send pictures of themselves with the hapless Texas Ranger to newspapers out of cruelty or heartlessness; they do it innocently, as a hopeful appeal to other “folks” like them to show they got the best of the law, just like anyone done wrong by them would if they had the chance. They might post an Insta, or send a snap of their joke if they lived today, but they certainly wouldn’t think to murder anyone live on Facebook. Violence is a last resort for them, not a sport, and they don’t understand why it should be different for anybody else.

Roger concluded his original review of “Bonnie and Clyde” saying its Depression-era setting was almost irrelevant: “It had to be set sometime. But it was made now and it’s about us.” If it had been made now, fifty years after those words were written, I’m inclined to believe every film critic would still be saying the same thing—and how alarming, that half a century has passed and this movie still speaks as clearly as ever. “When we started out, I thought we were really going somewhere,” Bonnie tells Clyde near the end of the film. “But this is it. We’re just going.” It feels cynical or despairing to equate Bonnie’s words with America, or the American people, or the American writers and artists and filmmakers who were really onto something new and exciting back then, but I can’t help it; talks of nuclear war are in the air again, and we are still so far from where any of us want to be. I’m sure Arthur Penn and the rest of them all thought we were really going somewhere, too—somewhere more enlightened, more advanced, healthier and more beautiful—but it too often feels like we’re still just going.

MATT ZOLLER SEITZ

Like a lot of landmark older films, “Bonnie and Clyde” requires a bit of imagination to appreciate. Everything in it that once seemed shocking and new has become commonplace in films and on TV—well, everything except the tricky tone, which seems at once detached and powerfully immediate, and its deep connection to the history it moved through and the ideas it conveyed. These are the aspects of moviemaking that can never be photocopied, only approximated.

At the time, audiences and critics were drawn to the pop-Freud sexual tension between Bonnie and her “lover” Clyde, who can’t respond to her physically and experiences his only release when robbing banks and shooting guns, and to the bursts of graphic violence, which would be imitated in years to come, then one-upped, then made cartoonish. The slow-motion bloodletting of the film’s instantly notorious finale, which shows the lovers being raked to pieces by machinegun fire from hidden Texas Rangers, would be escalated by directors like Sam Peckinpah, whose 1969 Western “The Wild Bunch” climaxed with a sequence that felt a bit like the last two minutes of Bonnie and Clyde’s lives stretched into an epic set piece. In the coming decades, audiences would see the Bonnie and Clyde ending made more intimate and psychologically-oriented (in the final shootout of Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver” especially), turned into a reactionary turkey shoot (see the last act of “Rambo: First Blood, Part II,” where the Vietnamese meat puppets dancing in the hero’s gunsights are literally cannon fodder), and abstracted into a bullet ballet (see John Woo’s whole career, and a good portion of Walter Hill’s).

But whatever their merits or demerits, none of these movies ever recaptured the mix of shock and delight audiences felt when they beheld the newness of “Bonnie and Clyde.” In an American decade increasingly defined by the Pill and “Free Love,” here was a film in which the gorgeous heroine blatantly came onto her equally gorgeous boyfriend—it’s usually the other way around—and inspired only anxiety and embarrassment. This was a film that extended and perfected a lot of the games Alfred Hitchcock played with audience identification—the masterpiece being “Psycho,” a film that makes you sympathize with a woman who embezzles from her boss, the motel manager who stabs her to death and hides her body, and then finally the dead woman’s sister and lover, who’ve arrived seeking answers. You start out finding Bonnie, Clyde and the gang curious and odd and exciting; then you cheer for them as populist wealth-redistributors, the Robin Hoods of the American Depression; then you’re shocked and ashamed at ever rooting for them in the first place, once the violence becomes more stark and the film flat-out tells you “They are killing people who have nothing to do with The System, just because they happen to be in the way.” Then you go through a long period of not knowing quite what you feel about them, except pity at how deluded and limited they are. Then comes that spectacular finale, with blood spurting out of what looks like dozens of holes in the lovers’ bodies, and you feel horror and revulsion, because you’re watching agents of the state execute two people who, at that particular point in the story, pose no immediate threat to them.

One of the unstated points of that ending is to make audiences ask which scenario is ultimately more frightening: the possibility of a few thickheaded gangsters running wild, or the existence of a state that is empowered to assassinate such people without a demand to surrender or a pretense of due process. It’s essentially the same point raised by the end of Stanley Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange“—another film that seems hell-bent on out-transgressing “Bonnie and Clyde.” Alex the Droog is a thieving gang leader and rapist who beats people for sport, but does that mean the state should be able to torture him in captivity, rewire his brain and rob him of free will?

It’s rare these days to encounter a mainstream American feature that deals with such wrenching, basic matters in populist language, with suspense, humor, style and ambition. The closest equivalents recently have been the horror comedy “Get Out” and the neo-Western “Hell or High Water” (which also owes a bit to “Bonnie and Clyde,” come to think of it). The problem isn’t that nobody wants to make movies like this anymore, but that the marketplace has been reconfigured so that audiences aren’t interested in seeing them anywhere, except in art houses and film festivals (and maybe on Netflix), therefore exhibitors don’t want them. Character-oriented movies, as opposed to spectacles, are the province of TV now, for the most part. In 1967 it was a different story. Movies were things you saw not just for fun but to have something to discuss. The American character and the Western mentality (“Western” in the global political sense, not just the genre sense) were on a lot of filmmakers’ minds in the late 1960s and throughout the seventies. Two 1967 provocations, “Bonnie and Clyde” and “The Graduate,” kicked off the American New Wave by mixing generic or exploitation-movie subject matter (like bank-robbing gangsters), lush Hollywood production values, and some of the conceptual techniques that had defined European Art Cinema in the preceding decade. The resulting cocktail could be box-office magic if served up by the right barkeep.

Written by Robert Benton and David Newman and directed by Arthur Penn, “Bonnie and Clyde” was one of the decade’s most profitable films, and a flashpoint for arguments about sex, violence and politics in movies. It exploded across world screens in 1967, at the tail end of the Summer of Love and smack-dab in the middle of a period of domestic unrest (the Detroit riots had happened just a few weeks earlier) and the mechanized slaughter of U.S. involvement in Vietnam (by the war’s official end in 1975, over 58,000 Americans and about 3 million Vietnamese, North and South, military and civilian, were killed in action). The U.S. was just 22 years away from the victorious conclusion of World War II, the “Big One” as it was called—a war that, notwithstanding Allied atrocities like Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the bombing of Dresden, reassured Americans that God was on its side and it was the Good Guy in the quest for global domination. It’s astonishing to look back on the key films of the sixties and seventies and realize how many of them were questioning received wisdom, intelligently, clumsily, blatantly, cynically, but always as a matter of course, almost as if it were the duty of a popular art form to remind audiences that the images on that screen came from somewhere, and if you wanted to figure out where, you could look in a mirror.

Fathom Events presents “Bonnie and Clyde” in more than 600 theaters around the country this Sunday, the 50th anniversary date, and next Wednesday. It will play at 2 p.m. and 7 p.m. each day in most locations. For a full list of participating theaters or to buy tickets, click here.