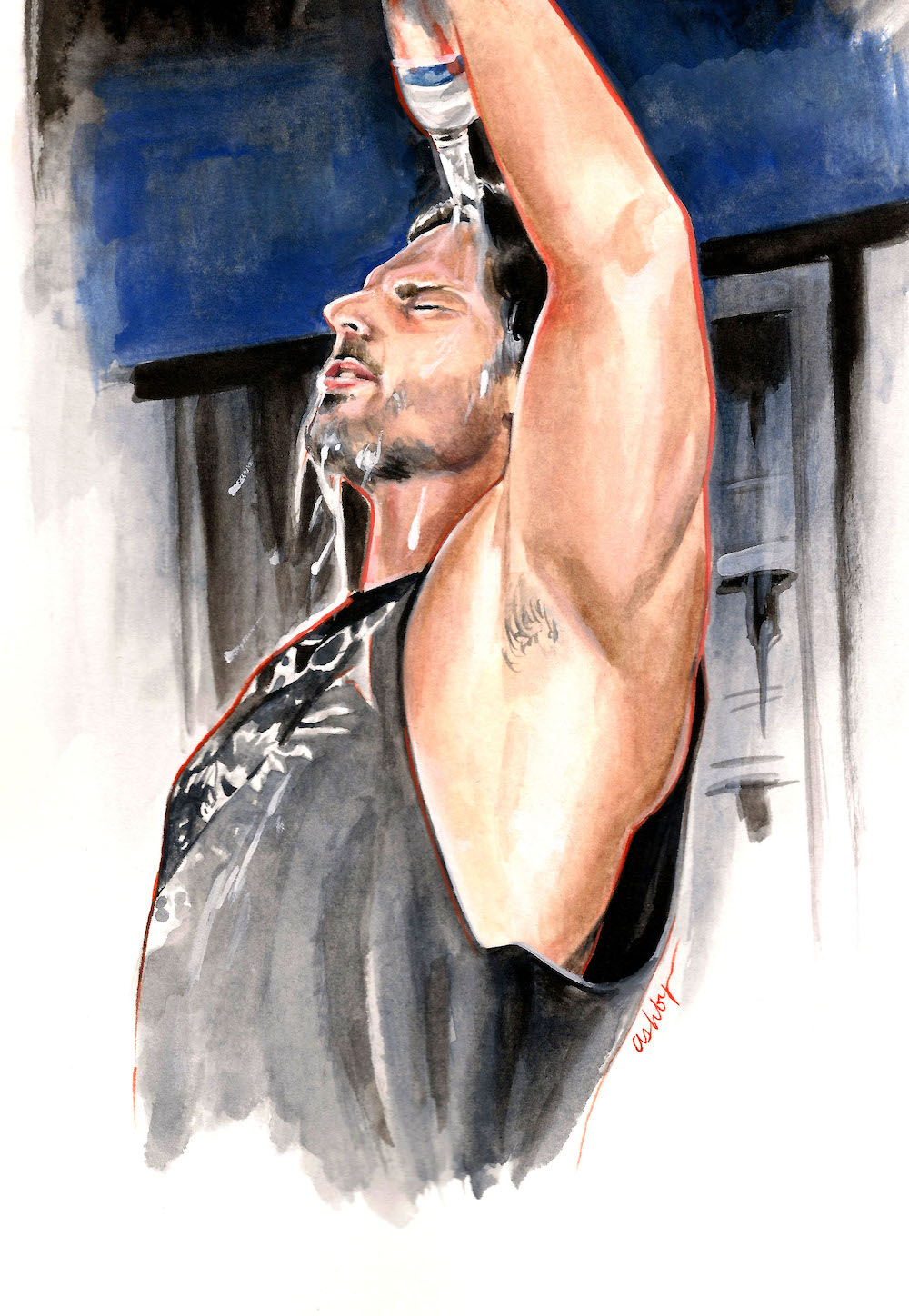

We are pleased to offer an excerpt from the June issue of the online magazine, Bright Wall/Dark Room. Their latest issue is about “thirst traps”—movies where an alluring surface masks surprising depths, for better or for worse. In addition to Isabel Cole’s essay below on “Magic Mike XXL,” the issue also features new essays on “American Honey,” “Spring Breakers,” “Saturday Night Fever,” “Interview with the Vampire,” “Sex, Lies, and Videotape,” “American Psycho,” “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” “Bull Durham,” “Last Action Hero,” “Widows,” “Walking Tall,” and “Breathless” (1983). The above art is by Brianna Ashby.

You can read our previous excerpts from the magazine by clicking here. To subscribe to Bright Wall/Dark Room, or look at their most recent essays, click here.

Reach To Your Heart

It’s actually pretty easy, even as a woman with notoriously unserious taste in film, to sell serious cinephiles and/or straight men on 2012’s Magic Mike. Yes, I came—sorry—for the butts, the abs, the herculeanly sculpted arms. But I received a story about the depressing underground economy of male stripping, about fallen innocence and aging into regret, about the slow crushing of humble hopes under the cowboy boot heel of the ownership class. Drugs. Capitalism. Soderbergh. Exploitation. Florida. Drop a few of these and your conversational partner starts to nod, preemptively pleased by the naughty trick of luring viewers in with the promise of hard-bodied titillation, only to serve a narrative steeped in cynicism and social commentary.

But like oh my God, who wants to dwell on yet another high-minded fable of moral decay? In this economy? No, what I need these days is something—forgive me—much, much harder. I need something that reminds me to want more than that grim landscape. Something that believes in fighting for small steps towards a different future. Something that—last one, I promise—pushes deep into the question of who we are beyond what this terrible world has made us, that values the pieces of ourselves we’ve been taught to cut away or push aside.

I need, in other words, the scene in 2015’s Magic Mike XXL where Big Dick Richie jerks off a water bottle while stripping to a Backstreet Boys song in a gas station mini-mart.

*

As with all great art, each component of Magic Mike XXL exists in conversation with the whole. So before we get there—to the mini-mart, to six guys rolling on molly and high on the possibility of change, to one vision of what it looks like for a person to reclaim their individual humanity after years beholden to a false self—we need to go back. Back, briefly, to that seedy underworld, to the grime and cheap thrills, to the long suffocation under the system’s iron grip. We need to go back to Dallas.

Dallas—not the physical city but its myth—holds a particular place in the American imagination. It conjures images of a specifically American brand of masculinity, an ethos of ruggedness and independence, oil money and guns waiting in their holsters, lone wolves and deciders who decide. Dallas, Matthew McConaughey’s drawling, smooth-talking club owner in Magic Mike, personified the film’s conception of American capitalism: seductive and flattering, avaricious and controlling, demanding complete fealty while harboring no loyalty to those whose bodies—those beautiful, beautiful bodies—created his profits and his power. Dallas made our heroes the Kings of Tampa, and he kept them there, trapped in the same old routines onstage and off, making enough to get by but not to get out. At the film’s end, Mike (Channing Tatum) did get out; the sequel finds him working to make his dream of a custom furniture business a reality. He takes a break from loading trucks and ferrying tables to listen to a solemn voicemail from his old coworker Tarzan (Kevin Nash): “I’ve got some real bad news about Dallas. He’s gone, bro.”

In fact, Dallas is not gone; Mike shows up dressed for a funeral and finds instead an easygoing bacchanal. Far from being dead, Dallas, like any successful corporate enterprise, is merely expanding his empire overseas, leaving behind the people who got him where he is. But this idea—Dallas is gone—reverberates throughout the movie, which is sun-soaked where its predecessor was dimly lit, generous instead of cynical, joyfully silly rather than insistently self-serious. Magic Mike XXL invites us to consider the question which animates its utopian spirit: what if Dallas were gone? How might we behave, no longer under his shadow? Who might we become? Would we continue to act out the roles he demanded of us? Or might we surprise ourselves? Might we find ourselves instead humping the floor at the foot of a cash register, mouthing along to Max Martin lyrics from 1999? Might the biggest surprise be that this is where we wanted to be all along?

*

Dallas is gone, and the gang’s reunited for one last ride, a make-it-rain extravaganza at the annual stripper convention in Myrtle Beach. But the radical possibilities of pleasure without Dallas don’t present themselves immediately. On the beach their first night out, dreamy hippie Ken (Matt Bomer) drops some passive-aggressive Oprah quotes that bring into the open the fact that not everyone has forgiven Mike for walking out on them three years ago. In response, Mike goads Ken to punch him in the nuts, insistently calling him a pussy until, against his own best judgment, Ken obliges. It’s a familiar cultural script—men solving problems with aggression, with their fists, with verbal abuse hurled at other men but casually degrading to women—which the movie treats like what it is: stupid macho bullshit that solves nothing and helps no one. “That was seriously fucked up,” Ken spits at the others’ appreciation as Mike hobbles off.

The old ways don’t work. They don’t heal the rift between Mike and Ken, they didn’t bring Mike true love. He had a life planned out with his girlfriend: “I had the house, I had the dog, I had Downton Abbey on the weekends; I even did the proposal on the beach with bacon and mimosas and pancakes and all that.” He did what he had spent years doing for Dallas—fitting himself into someone else’s picture of what a man is, carrying out a generic vision of what women want—and yet: “For whatever reason that I’ll probably never understand, she wanted something else.” The narratives he lived by left him clueless about the person he most wanted to reach. We have all inherited so many stories which wear the mask of love and yet leave us isolated with our pain.

That’s where Mike is—alone on the beach, nursing his wounds—when a photographer named Zoe (Amber Heard) snaps a picture of him peeing. They strike up a connection in which he is off-balance and she is playfully smug. There’s a flirtatious vibe to their banter, but each disavows the potential for sex. He’s not looking to hook up; she’s not in a “guy phase.” Their conversation passes in near-total darkness that renders them ghostly slivers, a deliberate rejection of any familiar visual language surrounding what happens when a man and a woman meet on the beach, so that we trust their intentions. This is not a meet-cute.

But it is a beginning. She teases him about the kinds of routines Magic Mike brought to life, poking at their clichés—“Are you cop in a thong? Or a fireman in a thong?”—and their hair band soundtracks. In the moment he shrugs it off, but that’s what it takes (well, that and a morning hit of molly) for Mike to start to wonder, three years out, about whether there might be a better way: an interaction with a woman in which they are nothing to each other except people, where the hurt he’s brought himself opens him to considering that maybe cop-in-a-thong set to eighties rock is as stupid as she made it sound. So even before Joe Manganiello starts flexing the biceps that look like they could bench press my whole body and then fold me like an origami crane, I am incredibly turned on because I don’t know about you, but for me, personally? All of my most erotic fantasies start exactly like this: I make fun of a man to his face until he acknowledges he’s wrong.

*

The stage is set for the pivotal moment: the boys in Tito’s (Adam Rodriguez) food truck, coming up on MDMA, listen as Richie (Joe Manganiello) outlines the plan. He names set pieces from the previous movie—the Fourth of July routine, It’s Raining Men—and Mike puts forward a revolutionary idea: what if they make up some new routines? The team is not receptive; even Ken, who rightly thinks the army routine is bad karma, points out they only have two days. As on the beach, the familiarity of the old ways is seductive. The fireman routine crushes—why question it?

But Mike, made desperate enough by how the old ways have failed him to start reaching for something new he can’t yet see, pushes: Did Richie ever want to be a fireman? Does he even like “Hotter Than Hell?” No, Richie concedes, he has a fire phobia; he only dances to the KISS song because Dallas picked it. Dallas forced on Richie a canned image of masculinity in which he had no interest and to which he was unsuited. Yet even now, Richie finds the prospect of a sure bet more enticing than the risk of stepping into a role that’s authentic but untested.

Luckily for everyone, that’s when the drugs kick in. In their chemically assisted creative brainstorm, Richie careens between hyped on his own idea and despondent that he’d ever pull it off. That’s how they pull into the fateful parking lot: equally thrilled and terrified by the prospect of discarding the selves they’ve learned to perform to let something real shine through. “I’m not a dancer,” Richie protests. Mike insists that it’s not about being a dancer, it’s about being you. That’s enough to light up a stage; that’s enough to bring a smile to an apathetic cashier, scrolling stone-faced through her phone. A challenge is set: Richie has to make her smile. If not, Mike will abandon his call for new routines. “Because you’re not a fireman, Richie,” Mike says. “I wanna hear you say it.” And Richie agrees, less confident but committed: “I’m not a fucking fireman. I’m a male entertainer.”

Thus Richie enters the arena: buoyed by his friends’ encouragement, exhilarated by the possibility of imagining himself into a more honest version of his life. Afraid, like most of us, that without the narratives he’s learned to live by, he has nothing to offer. And then he lives a moment familiar to anyone who found themselves on the wrong side of drunk at a dorm party in the first decade of the new millennium: “I Want It That Way” starts playing, and the whole world changes.

*

Joe Manganiello picked the music for this scene. It would have been a stroke of genius just for the hypnotic pull this song exerts on my generation, getting roomfuls of the most jaded and awkward to belt along with a fervor that pole-vaults over irony into full-throated delight; each of the four times I saw this film in theaters, it received vocal appreciation. But Magic Mike XXL is not a movie that contents itself with half-measures, and so the choice came with the insertion of dialogue earlier in which Richie vehemently defends BSB’s honor. This way, when we hear that melancholy guitar, we’re not just overcome with our own gleeful recognition—we know Richie, too, is experiencing the pop magic of affection both individual and collective, the drugstore mysticism that lends unmemorable radio stations the temporary sheen of the oracular. They’re playing his song.

And what a song! “I Want It That Way” is the Backstreet Boys’ most defiantly inscrutable hit, a perfect slice of teen-pop melodrama which is, as music critic Tom Ewing pointed out, mocked for the same thing that makes it a masterpiece: it just does not make any damn sense. Meaningless lyrics give the singers vowels to pronounce as they harmonize, while the sonics communicate sentiments—longing! regret! passion! desire!—with perfect clarity, like an Enya song crooned by puppy-eyed dreamboats. The band in fact recorded a version with more coherent lyrics but scrapped it because, I am not making this up, the feeling wasn’t the same. Which makes it an ideal fit for this movie in which moments of humor, discovery, reconciliation, care, and joy are all communicated through dance—and the perfect song to save Richie as he realizes what he must do: Don’t worry if it makes sense, or if you look dumb, or if anyone will get it. Stop thinking. Just feel.

He doesn’t get there right away. He tries one last familiar pose, bending down and arching back up; the girl doesn’t look up. The old ways have failed again. But in that failure comes freedom. Shoring up his resolve, he starts to move, easing into a strut, gaining confidence as the music works its magic. As the first verse winds down, he spots a bag of Cheetos: inspiration! He grabs it, swivels around, and then—perfectly timed to punctuate the beat kicking in—he rips it open.

Cash Register Girl is paying attention now, curious but impassive. That’s okay; he’s putting on a show. He thought he couldn’t perform without someone else calling the shots, without molding himself into something acceptably familiar and personally uninspiring, but BSB has shown him the error of his ways. He tosses the bag with a playful smirk. He grinds up and down the cooler, swinging his hips, not bothering to check if she’s still watching. On the stroke of the first chorus he flings open the door, he does filthy things with a water bottle, he…whatever, I’m dancing about architecture here, go find the scene.

The important thing is this: he is in his power. Not a power like Dallas, that seeks to dominate or control, not a power rooted in the successful evocation of images we have been told over and over again are powerful. Richie is in his power because he is rocking out. He is lip-synching. He is doing the choreography from the actual music video. He’s having fun. When he whips off his shirt, it’s not hot because he has more abdominal muscles than all five Backstreet Boys combined. It’s hot because he no longer cares about coolness or convention. It’s hot because fearlessness is fucking hot. Being your whole self is fucking hot. Being brave enough to cast off the roles which have kept you both secure and ill at ease, the roles everyone agrees comprise you but which have never actually spoken to who you are inside—that’s hotter than goddamn hell.

Finally he leans over the counter, glistening and out of breath, to utter the gorgeously incongruous line: “How much for the Cheetos and water?” Of course Cash Register Girl laughs, how could she not? When Channing Tatum described this movie as existing “in the world of men trying to figure out who they are…and that in turn makes them more interested in what and why women want what they want,” he was talking about this: the connection that can happen when you trust yourself enough to write your own script. The joy of reaching inside and out without preconceptions, with open-hearted curiosity. The way that when you finally start to answer honestly the question Who am I?, you can also start to ask: Who are you?

*

“I Want It That Way” is relevant for another reason. Any perusal of online fan spaces reveals that the appeal of the boy band resides not just in the assortment of individual flavors on display, but in the spectacle of male friendship put forward by the collective. On the potency of this fantasy I’ll just say that after enough time nursing boys through various stages of psychological collapse—my own fireman routine, a dance which simulated closeness while keeping my heart unreachable—the desperate wish for them to find any other source of emotional intimacy became a matter of both empathy and self-preservation.

So too with the men of Magic Mike XXL. Their unofficial boy band offers a range of delights for the audience, but truly shines in how they support each other. After their altercation on the beach, Mike and Ken talk it out. The guys commiserate with Richie’s romantic struggles. Mike offers to look over Tito’s business plan. When Mike checks in before the big show, Tarzan shares that he didn’t call to fuck with him; he missed Mike. The promise of a world without Dallas is one in which men can speak plainly to each other about their feelings, without deceit or obfuscation.

The sight of Richie gyrating in the snacks aisle to those late-‘90s harmonies would alone make this moment a cinematic classic, but what truly elevates it to the level of the sublime is that throughout the scene, the camera keeps cutting to the other guys in the parking lot, watching him. They chant “BDR!” as he enters. They shout encouragement like parents at a Little League game as he finds his groove. They nod in eager anticipation as he rolls a water bottle along his body, and cheer when he hip thrusts a stream of it across the store. When he crosses to the front, they race to keep up with him, pressing their faces against the window with kids-at-a-candy-store glee. And when he gets that hard-won smile, they erupt in whoops and fist-pumps and hugs, celebrating his victory as their own.

Because it is a victory for all of them. Richie made it because of their belief and affection and illicit drugs; in freeing himself, he proves to them that there is life after Dallas, and it can be so much better than what came before. They pile onto the bus, ecstatic at having witnessed someone stepping into his truth, and throw the old props out the window, bidding farewell to the iconography of masculinity that kept them stuck as something less than themselves. They carry the lesson of the mini-mart—that nothing is sexier than daring to show exactly who you are—all the way to Myrtle Beach. Erstwhile actor Ken sings his own backing track, aspiring fro-yo artisan Tito gets dirty with chocolate sauce. Amateur painter Tarzan brings a woman onstage to paint a glittering portrait in between flexes, and monogamy-seeking Richie pantomimes the nuptial day, from vows to consummation. Mike, who left this world to create things with his hands and came back because he was tired of being alone, builds a massive wooden frame to anchor the mirrored synchronization of a double act. They bring the house down in shrieks and laughter and moans by inhabiting their truest selves.

And their emcee for this event, the avatar of the world they’re creating, the movie’s most explicit alternative to the cold, mercenary order of Dallas? A woman named Rome.

*

It was common, in the months after Magic Mike XXL’s release, to hear it described as a movie for women. I get it, to some extent. Beyond the dancing scenes, lovingly shot to capture every bead of sweat, there’s real care in how the film treats women, revealed throughout in details big and small. The fact that Richie’s big dick realistically puts off sex partners. The tossed-off way Mike refers to God as “she,” and then explains “Yes, my God is a she,” almost sheepishly, like he knows it might come across as performative. The group’s righteous indignation that a woman’s husband won’t have sex with the lights on. The fact that when Mike reunites with Zoe, all he wants is to give her what Richie gave Cash Register Girl: a smile.

But the categorization of “for women” does the movie and its audience a disservice. It carries some aggressively straight assumptions, excluding both women who have no interest in the beefcake buffet and men who do (not to mention those who are neither) in a way that feels inimical to the spirit of the movie, in which the guys hit up a drag bar as a convention weekend tradition, Zoe’s guy phase shows no signs of reappearing, and heterosexual men straightforwardly admire each other’s beauty, athleticism, and erotic skill. It obscures the fact that it’s a movie about men, interested in undoing the ways men are warped by the expectations of gender. And it’s condescending to the women who do love this movie, like we’re a bunch of hormonal creatures too dumb to tell the difference between hot and good. Depressing, too, because if we accept it at face value, then our wildest, most forbidden fantasy is, what, that men could be nice to us? That they could think for five seconds about what our lives are like? That they could talk to us like people? I have to believe we can want better than that for ourselves. I think Magic Mike XXL wants us to want better than that.

Let me be clear: I absolutely want to fuck Joe Manganiello. But that has nothing to do with my love for the film. When I watch this scene, I don’t want to be Cash Register Girl, pleasantly bewildered by the deranged Backstreet Boys fan invading her workplace. I don’t long for a handsome stranger to work up a sweat all for the sake of making me smile.

I want to be Big Dick Richie, drenching myself in water to the beat of my favorite song. I want to be that alive to the present moment, that connected to my own heart. I want to be that fearless in the face of unmaking the selves which no longer serve me, that committed to spreading the joy of self-creation. And I want that for all of us: the thrill of discovery, the celebration in the parking lot. The smile that proves we were right to follow our instincts. We were right to question the stories that constrained us, keeping us separated and stuck. We were never firemen. We were always so much more.