We are pleased to offer an excerpt from the latest issue of the online magazine, Bright Wall/Dark Room. The theme for their July issue is “Erotic Thrillers” and, in addition to Elizabeth’s piece, also includes new essays on “Crash,” “Jade,” “Body Heat,” “Piccadilly” (1929), “The Sopranos,” “Body of Evidence,” “Final Analysis,” and more.

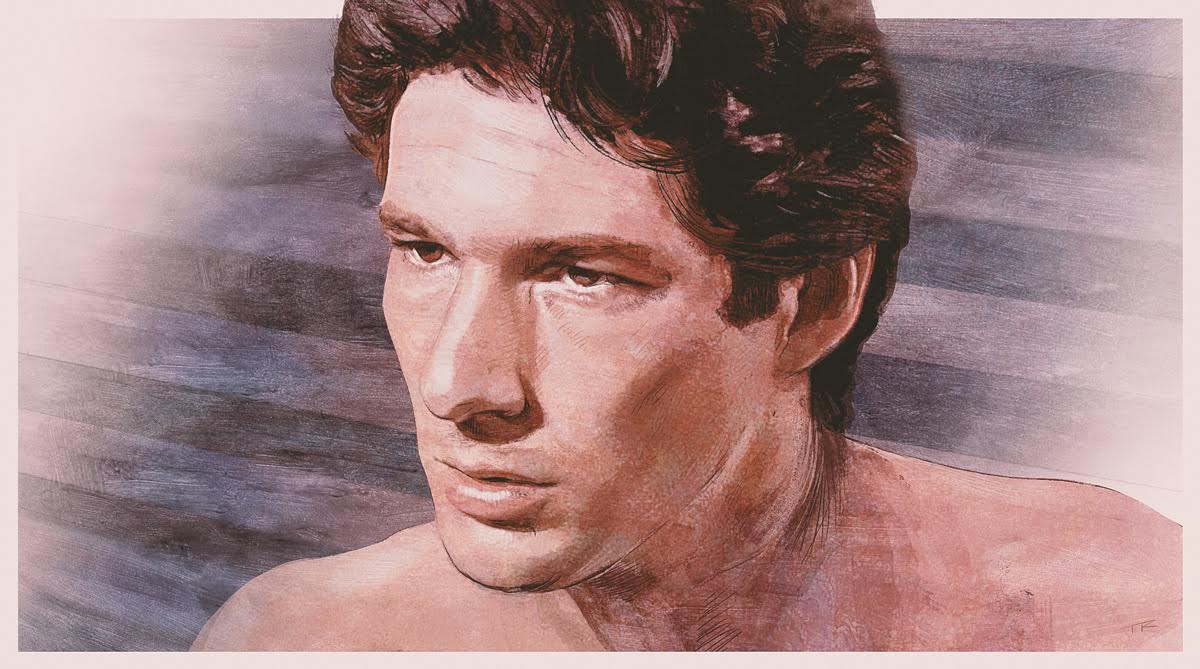

You can read our previous excerpts from the magazine by clicking here. To subscribe to Bright Wall/Dark Room, or look at their most recent essays, click here. The above art is by Tom Ralston.

One of the beautiful things about human beings and love and lust and tension is that our brains are capable of finding a wide range of things sexy. It varies from person to person, of course, but one might locate an erotic shiver in the way the back of someone’s neck looks when they walk; in the brush of the back of a hand along a thigh; in a sustained moment of perceptive eye contact during a tense situation; in a laugh, a twitch of the eyes; in the wildness of a spontaneous decision; in the vicinity of pain, implied or inflicted; or, alternatively, in some gesture of ultimate, genuine kindness: smoothing one’s hair back when they are sick, remembering to hand wash a favorite mug. For most people, though, the sexy thing is something other than sex itself.

Erotic thrillers are no exception to this rule. The appeal of these films hinges not on their sex scenes, but on some other element in the film that knows how to turn its audience on: voyeurism, often, but also anticipation, and escapism, and anger, and the pursuit of individual freedom, and all kinds of gazes. Paul Schrader’s classic 1980 neo-noir American Gigolo is no exception to this rule; the sex in it, as in many of Schrader’s films, is portrayed in a somewhat cold, removed manner. And yet, as practically every article ever written about Richard Gere seems contractually obliged to note, it is this film that propelled Gere to “sex symbol” status. American Gigolo set him up for a career defined by an appeal that seems, in the course of his filmography, capable of shifting from the fantasy of the heroic sexy savior (An Officer and a Gentleman, Pretty Woman) to the unhinged romantic sexy criminal (Breathless) to the angry, sexy, sometimes corrupt cop (Internal Affairs, No Mercy) to the determined, sexy, boundaryless psychiatrist (Final Analysis) to the wronged, sexy, vengeance-fueled husband (Unfaithful) to the extremely non-threatening, mainstream-sexy rom-com lead (Runaway Bride, Shall We Dance) and beyond. What’s more, Gere is good and convincing and compelling in all of these roles. He can shift his appeal from “bad” to “good” in a way few other actors seem capable of doing; James Spader, for example, exists largely in the “bad/dangerous” category of charisma, while Robert Redford primarily played “good/virtuous” sexy.

So: American Gigolo helped create and define Gere as an actor with uniquely chameleon sex appeal. But how?

The premise of the film, if you haven’t seen it—which, in my humble opinion, you should, because it is both great and kind of sad and weird!—is that Julian Kaye (Richard Gere), a gigolo who prides himself on being somewhat upscale and catering almost solely to older rich white women, gets framed for a murder he didn’t commit. His friend Leon (a fantastically chilling Bill Duke) asks him to “sub in” for a trick in Palm Springs that ends up being a troubling sado-masochistic gig (the husband’s desires and willingness are clear; the wife’s, not so much); Kaye reluctantly does the job, only to find out later that week that the wife ended up dead, the husband conveniently has an alibi, and Kaye has become the primary suspect. He subsequently loses both his standing in the older rich white woman community and his grip on reality. Meanwhile, he’s involved in a love affair with an up-and-coming politician’s wife, Michelle Stratton (Lauren Hutton), and has to navigate both their relationship and his own legal jeopardy. The heft of the film, however, lies simultaneously in its visual style and in Gere’s own stylized performance as a man who lives not to inhabit his own emotions, but to reflect back the desires of others.

He walks through hallways like a prowling ghost, skin whatever color the lights are.

*

Color me your color, baby, / Color me your car, Blondie sings, as we open on the spinning wheels of the film’s iconic black Mercedes 450SL, its vibrating tail light. Cars are often feminized, eroticized; Julian Kaye’s car, however, is less emblematic of a woman and more a steel cage for Kaye’s own body—the empty vessel in which women in the film want to be enveloped. For a while, the camera lingers on the car at an angle that blocks Gere’s eyes and forehead out, and only slowly shifts to one in which Gere’s face is striped with a car-windshield-shadow blindfold—the car is the face, the metal the window to the soul.

Julian is a shape-shifter, and his car is the mold he pours himself into at the beginning and end of every day. He is comfortable in his car, as he is comfortable in his clothes—other structured containers for his restless, amorphous spirit. Julian’s secret to success, of course, is that he can be whatever his clients need him to be; he is a remarkably selfless gigolo, focusing his talents on becoming whoever the woman of the moment wants. He does not come across as particularly smart, but he has learned “five or six” languages, and is working on a seventh, Swedish—the better to communicate with wealthy, retired, traveling women in their own tongues. He can be a chauffeur, a former pool boy, a translator, a tour guide, a comedic pal, or—in a dark moment, one the plot hinges on—the proxy for a husband’s abuse. He can be anything but sincere, because he is not a man; he is a car, a tie, a polished shoe. He is a vector, a way to get from old and dry to vital and wet. He is well-oiled, fluid, even in his gender and sexuality; “Julian” easily becomes “Julie,” and the deep resistance he has towards taking on gay clients perhaps indicates a part of him he is reluctant to explore. He slips down roads easily, he runs on something dug out of the depths of the earth that is primitive and limited and deadly, that we desperately need to wean ourselves off of. He will have to tear himself apart to save himself.

But he doesn’t know that yet, at the start of the film, when his car is still beautiful, incapable of admitting a single dent, intent on fitting its form to the curve of the roads around it, perfectly parallel-parked, and innocent, innocent, innocent.

*

The first time I watched American Gigolo, I saw mostly the colors and the shadows; the second time, I noticed the mirrors. Julian is framed in mirrors over and over again—yet another existing form to pour himself into, and, conveniently, one that serves his purpose of reflecting back to others what they want to see. In one of my favorite sequences, relatively early on in the film—after The Bad Thing has happened but before Julian realizes it’s happened—he gets himself ready for the day ahead, swiping a little of last night’s coke off of a mirror, singing along to Smokey Robinson’s “The Love I Saw In You Was Just A Mirage.” Gere’s performance is pitch-perfect here. He cocks his head, purses his lips, steps around jauntily, throwing jackets, shirts, and ties down on the bed with the relaxed, self-satisfied abandon of a man who knows he’d be beautiful in whatever outfit he chose to inhabit that day. A tri-fold mirror hovers behind him, and when he finally picks out his outfit—Armani, of course—the camera starts on his legs and slides up. Focus racks off of the man to his reflection in the mirror.

I could absolutely be wrong about this, but my gut instinct is that the opposite type of shot is much more common—I can think of countless scenes in movies where the camera starts on a reflection and later moves out to reveal that you were looking in a mirror, only to settle on the character in the flesh. These types of shots seem often to set off in the viewer a subconscious understanding of a dualism or split at work either in the character or in the film as a whole; I’m thinking, for example, of the shot in The Shining where we move off of Jack Torrance’s reflection, complete with backwards text on his T-shirt, to reveal him eating breakfast in bed, and we know something is very wrong with him in a deep way. But to move the opposite way—from the character to the mirror—seems to me to reveal something more subtle but just as disturbing. We are dealing here not with a split in the character, but with an emptiness, a flatness, an absence of depth; we move from three dimensions to two and settle there.

When the camera does rest on Kaye’s reflection, he repeats some Swedish phrases to himself, phrases he’s learning in order to meet and escort a high-priority Swedish client flying in later that week. Interestingly, the shooting script contains the following directions:

Playing two characters, he speaks to himself as he dresses. ONE CHARACTER, amiable and outgoing, asks the questions; ANOTHER, reserved and paranoid, answers them.

Schrader specifically wanted Kaye to be moving between personas here, and both personas are characters.

The mirror lies only in indicating that what it reflects is solid.

There are so many mirror moments in this film—Julian checking his reflection in store fronts, in his car’s rear-view mirror; Julian approaching Michelle Stratton for the first time in a mirror-backed booth at a hotel restaurant; Julian bantering with a not-so-easily-charmed cop (Hector Elizondo) in the midst of several mirrors placed on different walls in a hotel barber shop; Julian seen tellingly through a one-way mirror in a line-up; Julian, defeated, striped with the shadows of venetian blinds, sitting in front of that iconic tri-fold mirror behind his bed; Julian and Michelle, in a state of despair in front of a restaurant bathroom mirror—that it starts to become more interesting to note the scenes in which mirrors are conspicuously absent, in which Julian must rely on the people around him (if there are any) to reflect back a version of himself that he can live with. It’s a beautiful kind of personal recursion—he reflects the seductive and beautiful women they dream themselves to be, their eyes reflect back a person who is reflecting their platonic self, and everyone can drown in reflections to their heart’s content. There is no beginning and no end. The reflection eats itself and comes up more than satisfied.

Because, of course, what’s so erotically compelling about Julian Kaye—and about Richard Gere, whose career arc was shaped by this very specific film—is that glassy, crystal-clear reflective quality. On some level, of course, everyone knows that mirrors are erotic; it’s one thing, of course, to savor the appearance of the incredibly attractive person you’re with in the moment, but that feeling goes to another whole level when you can also see yourself with the incredibly attractive person you’re with in the moment—when you can see yourself, I suppose, as they see you. When she first enters Julian’s apartment, Michelle jokes that she thought it would be different—“I would have thought that you’d live in a place with, um, thick red carpet—big circular bed, mirrors on the ceiling.”

What Michelle doesn’t realize, though, is that you don’t need mirrors on the ceiling when you have Julian. Pieces of their sex scene—the one real, explicit sex scene in the film—are shot from Julian’s perspective. We see what those mirrors would have shown Michelle: her own legs on the sheets (half smooth, half rumpled), her own breasts (cupped by Julian’s hands), her own calm gaze and soft smile at seeing who she could be in this bed. Less male gaze than mirror gaze, the scene fragments her body but crystallizes it.

Again, it’s not the sex that makes this movie sexy—it’s the implication that in Julian, you can become, as Gatsby would have wanted, the platonic conception of yourself, founded not on a fairy’s wing, but on a perfectly-coiffed, Armani-clad, impeccably-thighed, impossibly malleable man. And Gere knows how to pour himself into this role with an ease that gives the viewer goosebumps. His performance feels intimate and self-conscious in a confident way. The camera often finds itself following him from behind; the soft sway of his hips showing that he’s not afraid to take up space, the casual tilt of his head indicating a coy curiosity. Yes, he seems to say, I know there’s not much underneath this surface, but look what a beautiful surface it is. He is Narcissus’ pool, he is the wicked queen’s magic mirror.

Back to the script—even Julian’s surroundings are drenched in his desire to be able to perform in whatever pose you want him in.

Julian’s room, like his mind, is eclectic.

Stacks of half-read books and magazines are scattered across his large unmade bed.

Cassettes and records are mixed with shoes and shirts. A cold cup of coffee sits on the Times crossword.

A Ruscha print hangs on one wall. On another is a chart illustrating styles of 19th century furniture.

Every object is an extension of his probing mind: always curious, always learning, always assimilating.

The bland, pale gray walls of his apartment are actually anything but bland and pale gray in the hands of Schrader and cinematographer John Bailey; rather, they change their appearance in every scene. Sometimes they are lit with blue light, sometimes bathed in green, sometimes criss-crossed by the shadows of those Venetian blinds—like Gere’s face itself, which Bailey uses as a receptor, positioning him so that his skin takes on the tone of whatever is bathing his surroundings: the restaurant’s lusty red light, the nightclub’s cold blue light, the sickly green light outside the senator’s mansion, the inescapable barred light of the doomed.

Debbie Harry again: Color me your color, darling / I know who you are / Come up off your color chart / I know where you’re coming from…

Most of the time, Julian’s need to be realized by and reflected in his surroundings works out just fine for him. Early on, in his on-again/off-again procurer Anne’s house, as she mildly berates him for cutting her out of deals he’s been making with clients independent of her, there are no mirrors for him to access—but he can sit by a replica of a torso of Apollo; that serves quite well to reflect himself back to himself. (You must change your life of course, etc., but Julian doesn’t pick up on that. It really is a perfect shot.) The women he is with in the beginning happily show him that he is useful, that he has, if not a clear soul, then at least a clear function. (He is a car, remember?)

That’s why Julian’s bedroom doesn’t look the way Michelle has assumed it would; he can’t see himself as a working gigolo. “A bordello,” Kaye interrupts her when she details her imagined version of his bedroom, disgusted. “This is my apartment. Women don’t come here.” Women don’t come here because it needs to be Julian’s backstage, his blank canvas, a place in which he can convince himself that he is something other than what he really is. After all, the brimming meniscus of confidence he has in his body is offset, in Gere’s calculated performance, by a frightening lack of confidence or solidity in the self. And holy shit is that sexy. I love a man in crisis; better when it’s a private crisis, of course—one you could convince yourself was fixable with the gauze and medicinal ointment of your love. Nothing disarms me more than a man on the verge of dismantling himself.

Gere looks fantastic throughout this whole film, but the scene in which he exudes the most undeniable appeal comes late in the movie, when he realizes he’s been trapped, snared, framed. The sound momentarily drops out of the film, and we follow Julian from above, striped and shadowed, staring at the possessions he accumulated just to be what others needed, knowing that somewhere, planted evidence lies dormant, waiting to send him to jail. The menacing soundtrack begins to fade in as Julian rifles through books, stands on his couch, takes his art down, upends his decorative fruit. Gere’s performance starts small; he’s not Nic Cage-ing this, or Al Pacino-ing it; he knows he’s not inhabiting a character who wants to go big and dramatic. Julian wants to stay smooth, silky, fluent. But as the scene proceeds, his movements lose a little of their control, his prowl loses its grace, his shoulders lose their poise, his jaw moves forward, his eyes harden—and that is the money shot, there, that moment where he throws the vase and the diegetic sound comes back into the film, taking precedent over Giorgio Moroder’s velvety, pulsing soundtrack. For the rest of this scene, yelling, knocking lamps and radios over, upending the bed, quietly loosening his tie in resignation and beginning to unbutton his shirt, Gere has me in the palm of his hand.

*

Symbolically, we’re now at the place in the film where we realize Julian has to take himself apart in order to rebuild. The apartment that was his blank slate haven is in shambles, and then he descends even further: to that beautiful, perfect car. Of course this would be the locus of the deception, the structure he has to pry apart, the frame that would contain an ugly betrayal. Why would he have thought anything different?

Where is the appeal in a man who doesn’t need to crawl underneath himself and emerge, slick with his own oil, determined to root out the evil? The scene where we witness Julian tear apart his own Mercedes might be more sensual than his sex scene with Michelle. It highlights one of Julian’s most appealing qualities beyond his reflective gaze—his vulnerability. We know, from early on in the film, that he is a man who could be broken. Though his first impression is one of complete implacability (those iconic upside-down sit-ups that I am sure inspired Patrick Bateman’s own morning routine! That self-assured chauffeur/pool boy act!), his meeting with Michelle shows the cracks beneath the surface. His slip-up, with her? He reads her wrong. Reading people is what he does, and yet—he believes her to be a tourist, to be unattached, to be looking for someone like him. He may have gotten that last piece right, but when he realizes he was wrong on the first two counts, we can see it in his entire body. Gere narrows his eyes a bit, hangs his head, nods a few times in sad self-recognition. “I made a mistake,” he says, his very simplicity and honesty vulnerable. And this, paradoxically, is what hooks Michelle—and, perhaps, the viewer—in. We know: Mirrors can break. Cars can only run so long on a single tank. The beautiful colored lights, eventually, will fail. Hair will gray, abs will melt. But fuck if that doesn’t make us want the fragile, breakable thing even more.

(I have not talked yet about one of the most notorious moments in this film: Gere’s full-frontal nudity, the first time a major Hollywood actor bared it all in a movie. According to Gere, the nudity was not in the script, and happened naturally; this makes sense, as it comes at a non-sexual moment. It’s powerful, though, precisely because it’s not explicitly there to arouse; it’s there to indicate the character’s casual relationship with his own vulnerable human self. What could be sexier than that?)

When Julian, a few scenes before, finally confronts Leon, whispering, helpless (and, for the first time, appealingly brokenly 5-o’clock-shadowed), “Why me? Why did you pick me?” Leon rasps, coldly, carelessly: “Because you…were frameable, Julian. You stepped on too many toes. Nobody cared about you. I never liked you much myself. Now get out.” Bill Duke’s performance here could not be more chilling, more designed to make someone feel invisible and pointless. You were frameable. For someone who has spent the movie seeking out those frames—in mirrors, in cars, in doorways, in shadows—it is a blow he can’t recover from. Julian Kaye, pushed to the edge of his emptiness, explodes—and like a black hole, the energy this emptiness can generate seems infinite.

*

As I write this, glaciers in Alaska on the edge of a heat dome are crumbling into the sea, producing “ice quakes” as powerful as small earthquakes. People in Vancouver died during a lengthy, unprecedented triple-digit heat wave. The midwest is being hammered by record-breaking temperatures. The New York subway is flooded. Politicians just like Charles Stratton (played by an appropriately slimy Brian Davies) are proclaiming their desire to wean America from fossil fuels while continuing to perpetuate systems that benefit giant oil companies, that require infrastructure that refuses, currently, to become sustainable. The reality of the global climate crisis means that the erotic thrust of our lives has to be decoupled from procreation now—that it has to be sublimated into escape. Take me under so that I don’t have to think about the smoke, the melting permafrost, the dying rainforests. Roll me in designer sheets, I’ll never get enough.

Stratton’s words are chillingly resonant—in a speech made to capture the wallets of wealthy Southern Californians who like to think themselves on the front lines of progress, he declares, “We have the technological means and know-how to help free America from the grip of fossil fuels…It is the privileged who should lead the way, who should set an example for the rest of the country.” He is backed, of course, by a large mirror. The older crowd has gathered there to see themselves as they want to be—an erotic act in its own way—selfless benefactors of a new order. We know, watching the scene, that nothing will change.

But Julian Kaye has a promise: he will see you as you want to be seen while the world around you crumbles. He can’t change the system; he won’t even try. He knows that’s useless. (Calm realism in the face of global collapse: another strangely sexy quality.) He may not love you; love may not even be something he can access at this point. He may not be a good person; he did kill Leon, albeit sort of rashly and with a subsequent (failed) attempt to save him. But look at him: even without the car, without the suits, with absolutely no mood lighting save the harsh fluorescents of a jail meeting area, he has those eyes. The final scene, of course, is famously lifted from Bresson’s Pickpocket—so, in a way, Julian is reflecting here someone he doesn’t even know, placing himself in the grand infinity mirror of art.

The camera is angled just so as to capture the barest ghost of an outline of Michelle herself in the jail’s dividing glass, layered imperfectly over Julian’s own face. Does he care for her the way she does for him? We’ll never really know. Gere’s performance, again, is keyed to just the right subtle tone. He closes his eyes, then opens them, the barest hint of a smile on his face: “My God, Michelle. It’s taken me so long to come to you.” Gere leans forward, and his career takes wing—his plient performance of ultimate surrender opens the door for him to be whoever the camera wants him to be in the future. And yes, oh yes, watching, we understand her impetus to sacrifice it all for this man, this pool of mimetic desire.

Any time, any place, anywhere, any way.