We are pleased to offer an excerpt from the December 2020 edition of the online magazine, Bright Wall/Dark Room. For their December issue, they have taken a different approach than usual, and are focusing on individual shots and frames from specific films. In addition to Lainey Wood’s piece on the “hand flex” frame from “Pride & Prejudice” (excerpted below), the December issue also features new essays on individual frames from “Field of Dreams,” “The Piano,” “When Harry Met Sally,” “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” “Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” “Mermaids,” “The Lego Batman Movie,” “Purple Noon,” “The Great Dictator,” “The Wrestler,” “The Sacrifice,” “Nosferatu the Vampire,” “The Hunt for Red October,” “Still Life,” “Home Suite,” and Derek Jarman’s “Blue.”

You can read our previous excerpts from the magazine by clicking here. To subscribe to Bright Wall/Dark Room, or look at their most recent essays, click here.

There are a number of striking, iconic frames in Joe Wright’s 2005 adaptation of Pride & Prejudice, so many that I could probably write this essay 15 times over. There’s the most obviously famous: the near-kiss at dawn in the misty field, the rising sun framed perfectly between the lovers’ shoulders as they tenderly take each other’s hands, all the quarreling and misunderstanding and family crises finally past. There’s the moment just preceding that, where Mr. Darcy (Matthew Macfadyen) emerges, white shirt unbuttoned and billowing, from a hazy morning palette of lavender and sage, looking, for lack of a more succinctly evocative phrase, like a snack. There’s the sweeping wide shot of Elizabeth Bennet (Keira Knightley) standing on a cliff in the Peak District, a shot whose sheer scenic drama seems more aligned with the expansive romance of the Brontës than with Austen’s usual restraint, but which nevertheless ended up on repeat as the home screen for the DVD menu. And there’s always Mr. Collins proposing to Lizzy in front of an enormous leg of ham, a moment at once excruciatingly awkward, brilliantly understated, hysterically funny, and delightfully memeable.

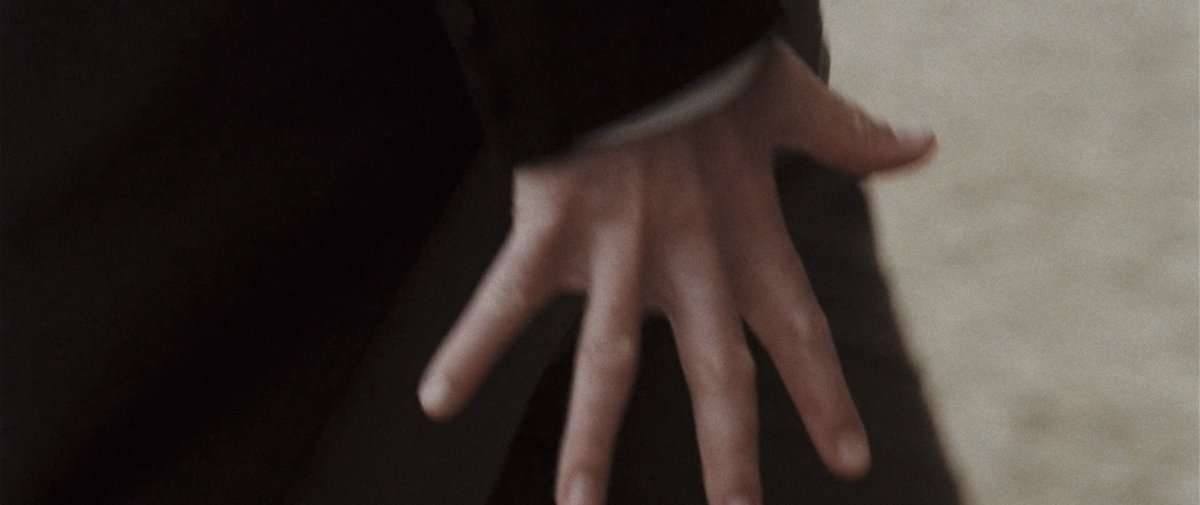

I want to talk about a different frame though, one which, if removed from its context, might not actually mean very much at all. I want to talk about that shot of Darcy’s hand.

[A quick disclaimer: For most of the time I spent writing this essay, I thought I was the only person obsessed with this particular shot of Darcy’s hand. I assumed that Pride & Prejudice was a niche enough film, and that this shot was a minute enough detail, that there wouldn’t be anything on the internet about it and therefore never typed Pride & Prejudice + Darcy + hand into my Google search bar. Reader, I was wrong. Turns out people were on that shit years ago. It also turns out that this year is the 15th anniversary of Pride & Prejudice, and as a result, the hand flex is getting a whole new round of attention. While a part of me wants to mourn the loss of my obscure, solitary obsession, it’s also kind of nice to see a Buzzfeed list and know that I’m not the only person who has spent the last 10-odd years watching this film over and over, trying to figure out what exactly makes this shot so compelling.]

The moment in question comes just after Lizzy’s visit to Netherfield Park to check on her sister Jane, who has fallen ill and must recover at the Bingley estate before returning home to Longbourn. After an afternoon spent volleying Caroline Bingley’s tediously pointed barbs about her family and sparring with Darcy over what makes for a truly “accomplished woman,” the carriage has been sent for and it is time for the Bennet sisters to return home. Lizzy says her goodbyes, including a perfunctory farewell to Mr. Darcy, and steps up into the carriage when a moment of surprise registers on her face. Seconds later, a close up reveals that Darcy has taken her hand to help her. The camera lingers for a beat, emphasizing the gravity of that touch, before cutting away to Darcy’s face. There is just barely a moment of eye contact as he turns away, his own inscrutable counterpunch to Lizzy’s terse goodbye perhaps, before the film cuts back to Lizzy, holding on her face as the shock and bewilderment of the encounter settles in. And then, finally, we get the shot of Darcy’s hand.

At first glance, this shot seems to be from Lizzy’s point of view as she watches Darcy walk away from the carriage. The previous pattern of editing—not just for this scene, but for nearly the entire film—has kept the audience with Lizzy at all times. Pride and Prejudice is, after all, her story, with the book’s narration coming primarily from her point of view and the arc of the story hinging on her characterizations of people. Wright’s adaptation holds true to this; we begin the film in Lizzy’s headspace, and as we move through different environments crucial to the story, we do so either through Lizzy’s eyes, or right by her side. This shot of Darcy’s hand, however, is a subtle, but important, deviation. The camera actually moves with Darcy as he walks away from the carriage, holding tight in a level close up, framing his hand against the black of his coattails, white shirtsleeve just barely visible. The color contrast between his coat and his skin makes his gesture all the more visible: a quick, almost involuntary, flex of the hand, stretching his fingers apart, as if he’s trying to remind himself of what his hand actually feels like, as if he’s trying to dispel the sensation of Lizzy’s touch from his skin.

Why am I so obsessed with this shot? First of all, it’s hot. This is about as overtly sexy as you can get in a Jane Austen adaptation. As any Austenite will tell you, sex in an Austen narrative, whether hinted at or explicitly referenced, generally happens off screen and usually connotes seduction or adultery, neither of which turn out well and often lead to complete financial and moral ruin. Even flirting plays out in decidedly non-physical forms: cross-ballroom stares, shared pianoforte duets, chaperoned walks into town. While physicality and sensuality are present in Austen narratives, they tend to operate as carefully constructed undercurrents, and with this shot of Darcy’s hand, Wright expertly runs the gauntlet. It’s thrillingly and modernly sexy without being too anachronistic, teasing future romance in the way 21st-century audiences are accustomed to without being so raunchy as to jolt seasoned Austen fans out of the moment. After all, we can imagine ourselves in a similar situation, waistcoats and barouches aside, where a passing touch with another person triggers that cascading set of physical and neurological responses that feel so much like an electric shock.

This shot also explicitly acknowledges, from the beginning, the physical attraction between the two leads, something that older Austen adaptations tended to shy away from. This is not to knock the lake scene from the 1995 mini-series version of Pride and Prejudice, which is iconic for a reason, but rather to highlight just how close to the surface the physicality in Wright’s version simmers. Darcy and Lizzy orbit each other with a buzzing magnetism that at times literally pulls the camera with them, and in other moments, like the first proposal in the rain, threatens to overwhelm the scene entirely. The shot of Darcy flexing his hand may be fleeting, but it is the moment that this physical tension is kindled.

It’s worth noting that neither Darcy nor Elizabeth wear gloves in this scene, which would have been customary at the time. According to the Jane Austen Centre in Bath, England, “during the 19th century, ladies always wore regency gloves outside (so did gentlemen). In addition, they wore them for the most part indoors as well (always at balls, for instance).” Lizzy doesn’t wear gloves once during the film, not even at the Netherfield Ball, where it would have been vital for both her and her family that she make the right impression. However, the other Bennet women all wear gloves, making their absence on Lizzy a deliberate choice by costume designer Jacqueline Durran to set Lizzy apart and highlight her rebellious nature. We know that Lizzy doesn’t care much for societal conventions—she arrives at Netherfield to check on Jane with her hair down and unkempt, the hem of her dress “6 inches deep in mud”—and her aversion to gloves further emphasizes this. It also makes the moment at the carriage that much more shocking and intimate, as skin-to-skin contact between a man and a woman would have been practically unheard of at the time.

Contemporary and historical sex appeal aside, this shot is also astonishingly efficient filmmaking. For any viewers unfamiliar with the story of Pride & Prejudice, this is the moment that clues them in, the one that says these two are supposed to be together, look what happens when they touch. Part of this is due to the brilliance of the actors; both Macfadyen and Knightley’s performances burn with a kind of contemporary intensity that livens the story and makes it not just palatable, but genuinely satisfying, for a 21st-century audience that has been trained to expect overt tension, if not full-on sex, from a romance film. Part of it is also the genius of the editing and the camera work. The whole exchange, from Lizzy’s step up into the carriage to the final cut away from Darcy’s hand, lasts 13 seconds. Thirteen seconds! Every single frame of the scene is communicating exactly what it needs to without a moment of excess. The camera lingers on their hands just long enough to spike our heart rates.

We get just enough of Darcy’s expression to note it but not read it, which makes the emotion evident in his hand gesture that much more powerful. The sequence leaves us desperately wanting more, while also being aware of the fact that anything more would ruin the moment, which is, at the end of the day, an exquisite replication of the agony of flirting in real life. Talk about an economy of storytelling: one of the world’s most iconic relationships perfectly summarized in 13 seconds. Joe Wright and editor Paul Tothill, I salute you both.

***

Why write an entire essay about hands? Because it’s an excuse to write an entire essay about hands. I’ve been obsessed with hands—and subsequently with gesture, visual communication, and the complexity of touch—for as long as I can remember. If I had to trace the origins of the fascination, it would probably date back to my early art training, to those years I spent in old, high-ceilinged, creaky-floored studios learning how to look for and capture gesture, how to model the body in planes of light and dark, how to take one line of charcoal and sum up the essential movement of a person.

Drawing, especially figure drawing, teaches you to look for narrative in the abstract features of the human body. You learn to both read and speak gesture, becoming fluent in a visual language that is so delicate it’s often barely perceptible. Beautiful, successful figure drawings are able to capture this delicacy, going beyond accurate anatomical study and reaching for some elusive element of personality or character, even when the subjects are meant to be anonymous. In this way, it differs from portraiture, which is meant to capture the essence of a singular person. You’re not often going to mistake a portrait hanging in a gallery for someone you know, or once knew, or once saw lounging in the park in a particular way that lodged itself in your memory. Figure drawing is different. In the anonymity of the bodies it becomes easy to recognize those little things that are, paradoxically, totally universal and utterly unique to human beings, and nowhere is this more evident than in the hands.

Consider for a moment the hands of someone you love, those of your mother, your partner, a grandparent. Can you picture them precisely? Perhaps you even have a photo you can reference. Take a second to enumerate their features. Calloused palms, swollen knuckles, dirt under the fingernails? Tanned skin or pale? Freckles? Age spots? Bitten nails? An elaborate manicure? Smooth skin that always smells like a particular lotion? Cracked skin from cold weather or frequent hand washing? Ink stains? Tattoos? Rings? Indents where rings used to be?

Consider now how this person uses their hands, the quality of their movements. Are they gentle? Tentative? Exuberant? Deliberative? Anxious? Commanding? There is a reason young artists are encouraged to start with hands. Our hands contain everything we are; they bear our history and betray our true feelings with startling accuracy, more so even than the human face. It may be considered new-agey and out there, but it’s no wonder we turn them over to palm readers to have our futures told.

Hands are also uniquely complex in the context of the human body. With 27 separate bones and an intricate system of muscles, tendons, and ligaments, our hands and fingers have the widest variety of positioning ability in the human body. That potential for movement has made them especially suited for communication since the early days of human evolution. There is debate among historians and linguists as to the exact origins of spoken language, but the “gesture-first” theory offers a compelling argument. The belief is that our oldest ancestors used physical signs and gestures to communicate, and over time those communications migrated from the body to the mouth. One particularly poetic theory from 1983 hypothesized that palmar pigmentation—the lighter skin on human palms and nails—developed as a way of reflecting light, making gestural communication more visible at night time. Accurate or not, it’s a nice image, not to mention a distinctly cinematic one: our earliest ancestors seated around a fire, signaling to each other in the flickering light.

***

For years, I have cited Wright’s Pride & Prejudice as one of my favorite films, and the one piece of art, regardless of medium, that has influenced my own creative work the most. It doesn’t matter if I’m writing a screenplay, photographing an old house, painting a portrait, or even setting the table for a holiday dinner; this film, with its glittering sunlight, eggshell palette, and lyrical beauty, lives in me at all times, stronger than a memory, something more akin to a chemical element of my blood. I would be a different person, a different artist, without it.

Consequently, I thought I knew everything there was to know about the film. But rewatching Pride & Prejudice with an eye toward gesture was like seeing it all over again for the first time. Suddenly every character was more alive, more vibrant in front of me. Mrs. Bennet with her hands in near-constant motion—wringing, trembling, bouncing a cup of wine, twisting a strand of hair— practically shouting “my poor nerves!” with every twist of her wrist. Kitty and Lydia, with all their wild, desperate clutching, seemed less silly this time round and more genuinely, authentically young. In one scene, Mary removes her gloves so sharply before plunking down at the piano that she might as well have looked right into the camera and delivered a Fleabag-style aside on the tediousness of her sisters. In another, an elegant Steadicam shot of the Netherfield Ball briefly dips to follow Mr. Bingley’s hands as he reaches to touch the ribbon on the back of Jane’s gown, a moment which utterly epitomizes Bingley’s persona with its pure, childlike tenderness. Tracking the characters’ gestures opened up a new level of depth not just to the performances of the actors, but to Pride & Prejudice itself as a piece of art. It also made the film seem—impossibly—even more like a painting come to life.

Watching this version of Pride & Prejudice feels something like witnessing a museum wing dust itself off and come alive. The antique patinas, slate blues and olive greens, 18th-century furniture with its cherry wood and finials, satins and brocades draped about, candle holders bolted to the walls, girls rushing and giggling, their skirts caught and swept this way and that, curls bouncing with every gleeful exclamation—these are the moments, the life force, behind those exquisite but staid portraits you see hanging on a gallery wall. Every frame is like a painting you could lose an entire afternoon in. And if Pride & Prejudice is a museum, and every frame is a work of art, then the shot of Darcy’s hand lives somewhere in between the Impressionists, the Old Masters, and a contemporary photography exhibit that’s just passing through, one you might happen to wander into out of curiosity or boredom, where all of a sudden you are faced with an image that sparks something—a memory of an old lover, perhaps, or a hope for some future flirtation—that lodges itself in the back of your brain and returns to haunt you periodically for years to come.

The shot of Darcy’s hand has, in a way, always felt like a sister shot to a particular moment in Atonement, another Wright film and one in which an instance of touch quite literally torments its main characters for the rest of their lives. There is a breathtaking symmetry between the shot of Darcy flexing his hand and the moment when Robbie places his palm on the surface of the water in the fountain, just after he and Cecilia have come dangerously close to acknowledging the desire simmering under their relationship. In both instances, a simple gesture is able to more efficiently convey the emotion of the moment than anything else, and in both films, hands become synonymous with desire, truth, and unexpressed feeling.

Pride & Prejudice’s portrayal of touch ends more happily than Atonement’s, but both have been on my mind of late as the whole world has been plunged into fear of human contact. COVID has made regency couples of us all, though I imagine most of us would prefer to risk our reputations, rather than literal life and death, for a fleeting moment of physical contact with another person. In “If You Knew,” poet Ellen Bass poses the question: “What if you knew you’d be the last to touch someone?” It is a powerful query made paralyzing by our current moment, one that forces us to consider how those little, accidental touches might just be the thing that makes us most human. “If you were taking tickets…” she writes, “at the theater, tearing them, / giving back the ragged stubs, / you might take care to touch that palm, / brush your fingertips / along the life line’s crease.” With the idea of visiting a theater, much less deliberately touching a stranger’s hand, unthinkable now, what are we to do to care for each other? To maintain, share, and communicate our humanity?

The final stanza of Bass’ poem, which has haunted me in the same way the shot of Darcy’s hand has haunted me, offers an idea. “What would people look like / if we could see them as they are, / soaked in honey, stung and swollen, / reckless, pinned against time?” There may be no replacement for human touch, but for the moment, perhaps sight—true sight—is a worthy substitute. After all, isn’t this what Love is? Sight that encompasses all things, radical understanding with an eye toward Time? And isn’t this ultimately what Darcy and Elizabeth do for each other? Learn to see each other exactly as they are? So, the next time you’re at the grocery store, or taking the metro, or picking up take out, consider the eyes of a stranger with the same kindness with which you might once have brushed their hand. Let them know that you’re still here, still human.