The Beatles song “Eleanor Rigby” famously imagines its eponymous heroine as a solitary spinster who attends a wedding wearing “a face that she keeps in a jar by the door,” then dies and is given a funeral to which “nobody came.” “All the lonely people, where do they all come from?” the chorus mournfully wonders.” “All the lonely people, where do they all belong?”

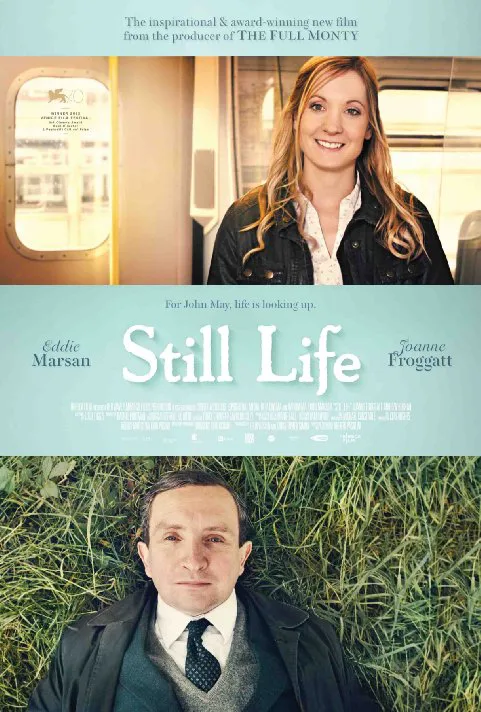

The British drama “Still Life” by writer-director Uberto Pasolini is pretty much an exact cinematic equivalent of Paul McCartney’s downcast lament. It begins with three funerals, of different faiths, at which there is only one mourner, the same in each case. He is John May (Eddie Marsan), a short, square-ish fortysomething who not only attends such funerals but also arranges them and even writes their eulogies.

This is his job, but it has also become something of a mission, even an obsession. May works for a council in south London where he’s assigned to arrange for the burials of people who die without any relatives or intimates to assist with their passage out of this life. Much like Eleanor Rigby. There seems to be a steady stream of such folk, since May has been employed for over two decades. And the government evidently has the largesse to allow him to pay for proper funerals, each with a clergyman, music, a good casket and a decent burial.

Since they have no one else, May regards the deceased as “his” people, and he goes to extra lengths to serve them well. Researching their lives as exhaustively as limited time and resources allow, he constructs the most favorable life narrative for each that he can, and this becomes the person’s eulogy. He also tracks down any lost relatives or friends and tries to persuade them to attend the last rites – usually without success.

Otherwise, May’s life appears to be neat, clean and empty. He’s like an amalgam of the protagonists of Henry James’ “The Altar of the Dead” and T.S. Eliot’s “Prufrock” – devoted to his dear departed while living a life measured out with “coffee spoons.”

After establishing May’s routines and rituals, the story take a turn when a young, officious new superior calls him in and tells his job is being consolidated out of existence. Apparently the bureaucracy would rather pay for simple cremations rather than funerals, and has no need for his personal attention to detail. Stunned that he’s only got a few days left being paid to pursue the quest that’s occupied his adult life, May finds a last case that he gradually begins treating as a grand cause.

As it happens, the deceased lived across from him, suggesting how modern city life divides communities into solitary cells. The man’s body had not been discovered for many days, but May enters his shabby, smelly apartment and, with his usual meticulousness, begins picking through his belongings (partly filled photo album, old LPs), looking for clues.

The portrait that emerges is one of a drunken, abusive, ne’er-do-well, just the kind of guy who would die alone and unlamented. But that doesn’t deter May, who puts his usual detective skills into high gear and tracks down a number of people who knew the man. They’re generally not happy to hear his name mentioned. A woman who runs a seaside fish and chips shop, who was his girlfriend two decades before, recalls him as violent and impetuous. Two homeless men, who served with him in the Falklands War, say much the same but allow that his roughness was useful in training for combat.

May also finds the man’s grown-up daughter (Joanna Froggat) working in a rural center for rescued dogs – a job that signals something of her feelings of abandonment. The last time she saw her dad, she says, he was in prison and punched out a guard. She’s grateful to May that he’s let her know the sad news, but she doesn’t want any further involvement with her father…until she changes her mind and calls the messenger back, sparking a connection between two lonely people that propels the tale’s third act toward an ending in which sudden surprise is followed by a bit of magical-realist uplift.

The film’s title says lots about its mood and style, which is heavy on becalmed views of rooms, objects like an apple peel and office utensils, and May’s glazed gazes at nothing in particular. Pasolini (formerly a producer of films including “The Big Monty”) says this approach is indebted to late Ozu, but it’s also one shared by many European art films of the downbeat-humanist sort. In terms of atmosphere, it conveys a kind of drab ordinariness that, for some reason, in English films, comes across as exceptionally dull, constricted and depressing.

The nuanced particularity pays its best dividends in the exacting, flavorful performances, especially Marsan’s Mr. May, who has a face like a squashed grapefruit, with doleful eyes, a looming nose and a stretched mouth that only really smiles when he meets his last client’s daughter. Whether filmgoers want to join his journey will be a matter of individual taste. Though the film’s lachrymose gist is conveyed with subtlety and insight into the rigors of loneliness and mortality, it is lachrymose nonetheless. Fans of “Eleanor Rigby,” in any case, should not miss it.