A video essay published in tandem with Indiewire

“The human face is the great subject of the cinema. Everything is there.” – Ingmar Bergman

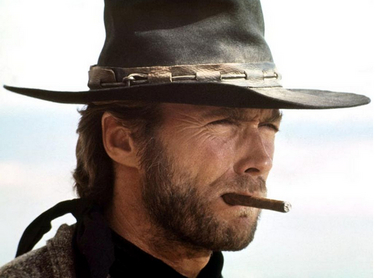

The craggy complexion. The stately ovate chin. Those thin lips deceptively wrapped around that charming smile. That perfect nose. Those clear greenish-brown eyes. That squint.

One cannot discuss Clint Eastwood‘s iconic stature in film, without mentioning his face. There are others that have been as handsome (Newman), masculine (Gable), striking (Hitchcock), fearsome (Bronson), and symbolic (Wayne). But from a visual standpoint, none of them have been as instrumental as a filmmaking tool or signature. Most actors are cast to fill in a character from the inside out, building an individual based on the personal. But Eastwood himself is a form. An absent presence whose persona is filled primarily by the film’s themes and ideas.

Clint Eastwood’s “Side View” profile is probably the most recognizable visage in cinema. On the one hand, it is the picture of a supremely good-looking and rugged individual. On the other, it is the quintessential outline of a man’s man, whatever that ideal might be: a tool that Eastwood uses to better effect than any actor could or would ever dare to try.

The first true film in which Eastwood’s profile became noticeable was in Sergio Leone’s “A Fistful of Dollars”. On casting him Leone said, “I looked at him and I didn’t see any character… just a physical figure.” In that sense, Eastwood might have been the perfect choice for the film. With Leone’s penchant for extreme close-ups of his characters’ faces, often exposed to the extreme heat of the desert, Eastwood’s rough complexion would reflect the barrenness of his environment. His “Hollywood” looks amongst his often less-than-handsome Italian co-stars would only further enhance his visual uniqueness.

With the succeeding “For a Few Dollars More” and “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly,” Clint Eastwood in a cowboy hat would become the image of the Western Anti-Hero: unpredictable in his actions, but always of noble intent. It would be the template that would follow him for most of his career. This profile would be passed from Sergio Leone’s “man with no name,” to Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry.

But Siegel didn’t merely carry on the tradition. He also introduced to Eastwood another artist who would help shape Clint’s persona: Bruce Surtees, the renowned cinematographer called the ‘Prince of Darkness’ in professional circles. Eastwood had strong directorial inclinations by this time. And with his founding of Malpaso Productions, further collaborations with Siegel and Surtees made them grow closer, personally and artistically.

Bruce Surtees’s refined use of shadow was perfect for Eastwood’s profile. With Surtees’s lighting expertise, Clint’s characters, often half-covered in black, suddenly had the additional qualities of menace (“Dirty Harry,” “High Plains Drifter”), disrepute (“Tightrope“), secrecy (“Firefox“) and struggle (“The Outlaw Josey Wales,” “Honkytonk Man“).

Clint clearly learned much from Surtees, as he applied the same techniques to his subsequent films. Who can forget Maggie and Frankie’s conversation about her pet dog while driving beneath dancing lights in “Million Dollar Baby?” Sgt. Tom Highway’s silhouette while leading a platoon in “Heartbreak Ridge?” The ominous shadows enveloping Will Munny in “Unforgiven?” Sometimes Eastwood used his profile in unexpected roles, such as the sleek fighter pilot Mitchell Gant in “Firefox,” or as the overage astronaut Frank Corvin in “Space Cowboys.” Other times he used it as emotional “filler” for a sparse storyline, embodying it with great pathos despite an economy of style or feeling elsewhere in the movie (“Escape From Alcatraz”).

Great actors are remarkable in their ability to embody characters that we recognize and believe, simply by looking in our direction. But Clint Eastwood’s face is in a class by itself; astonishing in its capability to serve as both character and cinematic imprint, simply by looking away.

Credits: Thanks to Donald G. Carder (@theangrymick) and Senses of Cinema (@SensesOfCinema) for additional research material.