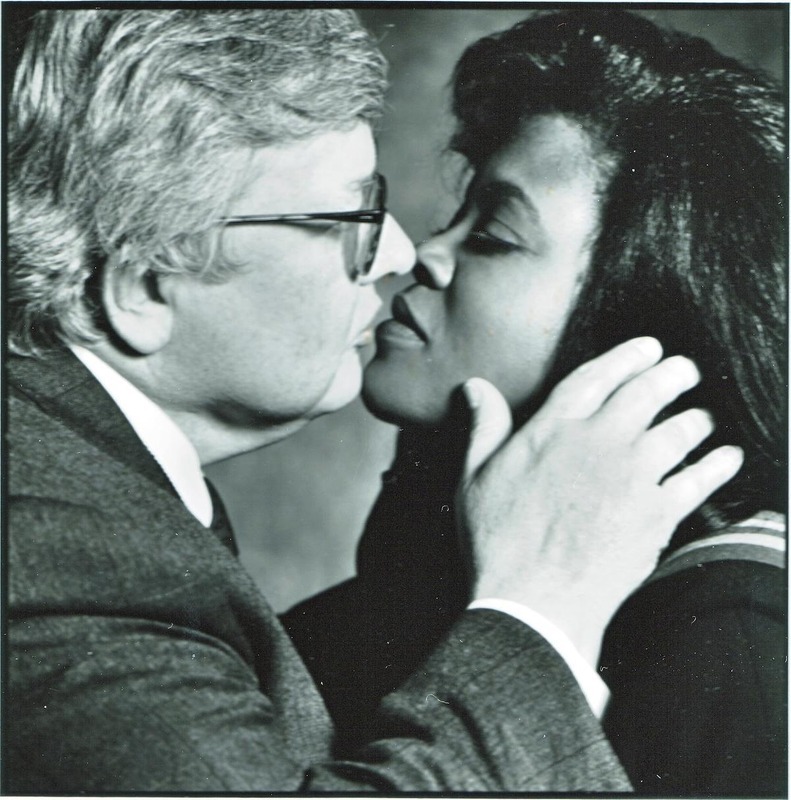

Can it really be 10 years since my husband Roger departed this earth? The day before he transitioned, I sat with Roger beside his bed in what was then known as the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (now the Shirley Ryan Ability Lab). We were both in good spirits having visited with friends who had come to Chicago to attend Verdi’s Rigoletto with me at the Lyric Opera.

Our first date, in fact, was Tosca at the Lyric on September 25, 1989. We both loved the outsized emotions one was allowed to express under the cover of a song. Your spirit was allowed to soar with intense feelings of joy or of sorrow; with deep feelings of longing or of peace, usually ending with the audience finding the core of goodness in the protagonist, and with the two of us squeezing each other’s hand a little tighter.

Roger was goodness with a capital G. I laugh at the trick the universe played on him by allowing him to be known as a “critic,” someone who criticizes the works of others. He was proud of his profession, and as a film critic, he was a fine one, one with a reputation that traveled the globe. While he published highly entertaining collections of reviews of films he disliked, he was especially proud of championing the films he loved, especially those films audiences might otherwise miss. He found his rhythm in those reviews that encouraged the greatest empathy.

Roger was always thinking about how he could be of service to others, be it through words or actions. He answered the many calls of volunteerism to help causes, especially ones associated with education and the arts. He donated money quietly to help feed and house and clothe those in need. He traveled far and wide to make appearances, often without pay, simply because he was told it would help. And one of his favorite things to do was to send books to people he knew and even to those he didn’t know, simply because he enjoyed reading and he loved sharing that joy with others.

But he also loved the connection he made with people through his writing, even to the end. One example of that was when his cancer came out of remission, and we thought he perhaps had two more years to live. One day, Roger, in his good-natured way, announced: “Why don’t I write a column about what it’s like to die!” He fairly shouted it out as if he were revealing the hiding place of Christmas presents. “Why?” I asked. “Because I’m dying, and I have been fortunate enough to see it coming. Besides, tomorrow is my 40th anniversary as the film critic at the Chicago Sun-Times and it would make a wonderful series.”

I wasn’t convinced – not about the series but about the inevitability of his death. We had been given both good news and bad news about his cancer prognosis. And I chose to believe the good news. Roger never got to write that series on death and dying. On April 4, as we were waiting for the car to pick us up from the rehab center to go home, Roger smiled and peacefully drifted into the afterlife.

He left with such a quiet dignity that it was hard to comprehend, at first, that he was really gone. In the immediate aftermath, I could feel his spirit in the room. He had that effect on people when he was alive, too. I cannot count how many times people told me they saw Roger at a theater watching a film, blinked and he was gone. He was out of sight but still left an impression.

I wasn’t ready. I thought we still had time.

We relaunched RogerEbert.com as a stand-alone site from the newspaper (we originally started it in 2002) literally days before his passing. Then, on April 2, Roger published his final column titled “A Leave of Presence” on our website, in the Chicago Sun-Times and across a wide swath of syndicated papers. That phrase, “leave of presence,” was inexplicable to his editors at the time. “Shouldn’t it be a leave of absence?” they asked. But no, Roger was insistent on those words. And those words have echoed in my head these last 10 years.

The column was meant to announce his decision to step away from the day to day writing to enjoy the last months of his life unencumbered by deadlines, except for the ones he self-imposed by whatever he chose to write about. Two days later, Roger took his leave of presence not just from the newspaper and his readers, but also from me, from our family and grandchildren, from our friends, from Ravenswood, our house he loved on the banks of Lake Michigan in Harbert, Michigan, and indeed, from this very earth. But somehow his presence is still felt.

My Eyes Into Yours, Painting by Kelly Eddington

Afterward, I felt I had to close off my heart to protect myself from hurt and harm. But the opposite turned out to be true. I just needed to take it a day at a time. Each day of grief was different. Some days were full, like when I was surrounded by family and friends who made me laugh as we celebrated all that was good and cantankerous and funny about him. Some days I allowed myself to just feel the pain.

And then one night I gave a speech at a Cancer Center at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago. I had heard too many people debate whether it was cruel to give cancer patients too much hope. Was hope just a means of denial. I knew how much hope meant to me, and so I wrote a speech that I became very passionate about called “Sometimes Hope Is A Strategy.” After my address, there was a long line of people waiting to talk to me and share their stories of impending death–more important–their stories of hope. Who cares about denial; we all need hope. We were bound together by it.

I stayed until I had spoken to every single person in that line. And then I felt it, the presence of that mysterious heart overflowing. I had become so open that it emanated from me. I could feel it and they could feel it, too. People were drawn to that inexplicable energy. They wanted to touch me, to shake my hand or caress my face, or ask me for a hug. And with each hug or handshake, or tear I wiped away from another’s cheek, I knew the answer was not in closing myself off, but in allowing myself to be vulnerable. I became open to connecting to the needs of others. To assure and be reassured. To love and to be loved. That is the healing I am hoping we can find in this divided world today. I want to return to that mysterious, inexplicable healing energy. It is more powerful than weapons of war.

I was reminded in that moment of the feeling of gratitude that I had somehow reached during Roger’s illness. It was such an unexpected gift amid the shock. But once he became clear in his conviction to live life a day at a time and relaxed into this attitude of gratitude, we both were able to breathe a little easier. We journeyed to a presence of love that needed no words, just the feeling of unconditional acceptance. Sometimes imperfect, but always imperfectly perfect.

Today I sit in contemplation and open my heart to the empathy Roger said we all need to practice in order to live together harmoniously. It is that place of wholeness and healing that I am holding out for in this world on this the tenth anniversary of his leave of presence. Roger and I both felt that it was goodness, not sadness, that causes us to well up with emotion. To know that someone is so good that they want to reach out to alleviate the suffering of others. Or when the bigness of a heart can forgive the wrongs of another and leave space for redemption and a return to the presence of love, a space of nonjudgmental healing.

Roger was one of the most generous souls I ever met. A renowned film critic, yes, but the good man I knew him to be was divine. I will not stop espousing the empathy that he said we could find in movies. I will make a declaration of a return to the presence of love. That feeling deep within us that causes our hearts to open to the possibilities of what can happen when we choose to see the good in another person. When we are meditative and still enough to see the light emanating both from those we love, but also from strangers, alike, and embrace them as though they were us.