When I was first learning to play the saxophone, my instructor taught me about “vibrato.” He explained that instead of simply playing a set of notes straight, I should attempt to pulsate the pitch of my playing in such a way that adds an element of modulation and expression to a song. Playing the notes accurately was one thing, but incorporating vibrato added personality and texture to a piece of music.

Director Nicholas Hytner’s historical drama “The Choral,” which focuses on a choral society that attempts to perform The Dream of Gerontius for their community against the backdrop of World War I, hits its notes with aplomb. However, it might have benefited from a creative vibrato that would have added more layers to its boilerplate narrative. Still, it’s a tune about the impotence of art making in the midst of crisis that bears repeating, as the world that’s all too eager to sacrifice the arts on the altar of productivity and progress.

Yet while the lessons of “The Choral” feel applicable to our present moment, Hytner is careful to ground its story in a richly realized setting of a different era. Set in the fictional town of Ramsden, Yorkshire, in 1916, the era is brought to life with meticulous detail thanks to Production Designer Peter Francis: schoolboys ride their bikes recklessly throughout the town, aristocrats cover their balding scalps with top hats, while steam from the nearby industrial mills wafts through the cobblestone streets.

There’s a verisimilitude of normalcy, although the regularity pokes at a more somber truth: the town is in mourning at the toll of the war, which has taken many of their men and left behind grieving families. The young men of the town wait with bated breath to see whether they’ll receive the call to conscription, leaving the rest of the citizens caught in a sort of limbo. It’s hard to go about one’s daily life when the people you’re in community with can be taken at any moment.

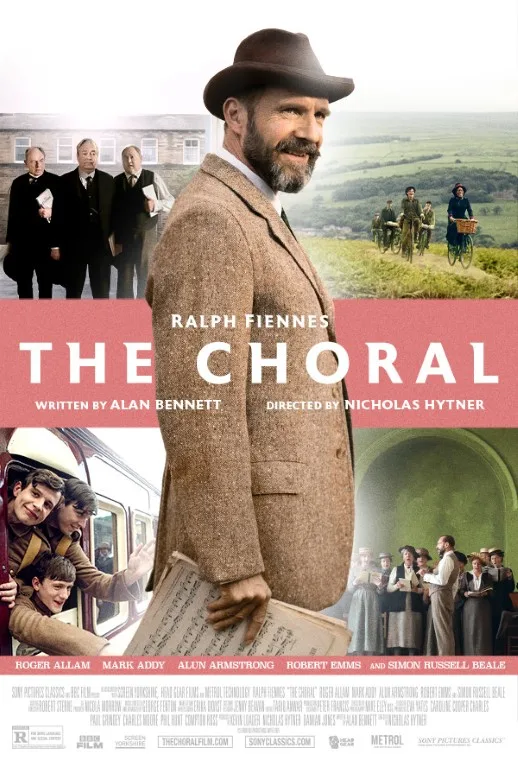

It is in this context that choral society leaders, Alderman Duxbury (Roger Allam) and photographer Joe Flytton (Mark Addy), are attempting to put on a production of Bach’s St Matthew Passion. Their choir master left to join the army, which leads the duo to hire Dr. Henry Gutherie (Ralph Fiennes). Guthrie is somewhat persona non grata due to having conducted music in Germany (and that he seems to remember his days there fondly) and his homosexuality (in England, homosexual acts were not decriminalized until 1967).

With the pickings slim due to the war, in a radical act, Gutherie expands the choral membership to any interested townspeople who can hold a note, gathering everyone from returning veterans from the war to local sex worker, Mrs. Bishop (Lyndsey Marshal). Riding the wave of iconoclasm, choral shifts focus on performing Edward Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius, another radical act given the choral members’ concerns around Elgar’s staunch Catholic beliefs.

Fiennes can play the gruff maestro with a sensitive heart in his sleep, though as Guthrie, he turns in a far more restrained and grounded performance. Guthrie is competent but constantly aware that his gifts only flourish in the context of a thriving ensemble, and this is something Fiennes seems to understand too; he grounds the film with a steady gravitas that allows the rest of the ensemble to shine. He may be the most recognizable name, but it’s a delight to get acquainted with talent such as Emily Fairn’s Bella, who is torn between waiting for her missing husband and pursuing a new relationship with a choral boy, as well as Amara Okereke, who plays Mary, a devout Salvation Army volunteer whose ethereal voice is the musical highlight whenever she’s given the spotlight for a solo.

Had “The Choral” focused on Guthrie and the arcs of these women, it might have been more compelling; Alan Bennett’s script gives more screentime to the churlish young men who join the choral while awaiting the verdict of whether or not they have to go to war. The women are framed only in their relationship to the men, whether they’re being pursued by them or fancy them. Some uncomfortable sexual comments and situations are played off as simple “boys talk” that may be period accurate, but don’t make it any easier to garner sympathy for the people we should be lamenting for their deployment.

On an aesthetic level, Hytner doesn’t rely on the plot’s sedentary machinations to keep the language dull. For a film that mostly amounts to witnessing groups of people standing or sitting while singing, Hytner and cinematographer Mike Eley find ways to keep those scenes engaging. Eley, in particular, favors long pans, especially when the choir is singing. It both showcases the group’s diversity and speaks to the free-flowing nature of the music, as if it were a spirit moving untethered.

One of the film’s core conflicts comes relatively late, when Elgar learns that Guthrie and the choir have revised his work, such as changing the main character from an old man to a soldier who has just returned home from war. In response, Guthrie challenges Elgar that art, whether created or adapted anew, will reflect in some way the era in which it is being produced. That’s not something to lament but to embrace, as a new time period may unlock a text’s potential in different ways. It can indeed seem foolish, in the shadow of all that’s afflicting us, to make music and be merry, but that’s a practice that should not be cast aside.

We need the gift of new narratives to help us imagine beyond present circumstances. While “The Choral” may be riddled with a few too many false notes for comfort, the purity of its song and message make it a hard tune to disregard.