If you’re a music lover of a certain age, you remember how exciting and polarizing the rise of Hip Hop in popular music was. From the amiable goofiness of The Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” to the scratching pyrotechnics and audacious musical mashups of “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel” to cosmic funk of Afrika Bambaattaa’s “Planet Rock” a whole world of exhilarating music emerged, even as a vast segment of the programming and critical population declared “That’s not music.”

It soon became clear that Hip Hop, at first a primarily New York-based phenomenon, wasn’t just music. It was multidisciplinary, encompassing fine art (Basquiat), television (alternative programming on public access cable), film, and more. Filmmaker Charlie Ahearn was making short films documenting urban martial artists (his first feature, from 1979, was titled “The Deadly Art of Survival”) when he encountered the characters—graffiti artists and turntable maestros who ruled the block parties that were crucial to the uptown scene—with whom he would populate 1982’s “Wild Style,” a still-startling document of Hip Hop.

“Style” is a seminal document, but it’s not quite a documentary. The artists here, including Lee Quinones and Fab Five Freddy Braithwaite, play themselves, or versions of themselves, for the most part. But they’re enacting a narrative about the purity of graffiti coming up against the commercial concerns of the predominantly white art world of lower Manhattan. From the NYC Transit Authority Yards, where spray-paint armed visual artists tag the sides of subway cars, to the white-walled galleries of Soho, just as it was becoming a monied art center, “Wild Style” is a fascinating ride. No, none of the personalities here would ever win acting awards, but their varied demeanors are always surprising.

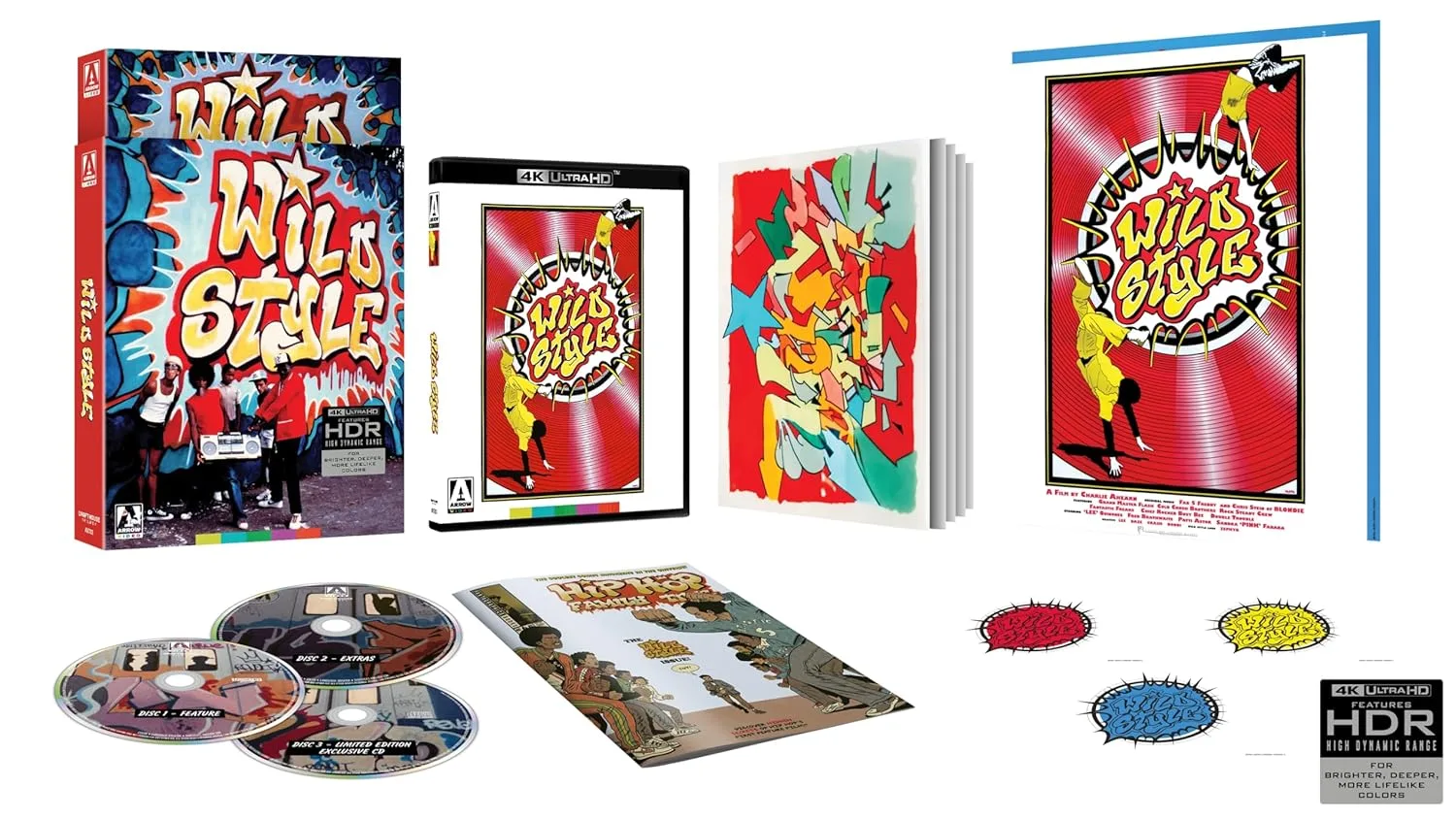

The movie is now available in a deluxe edition from Arrow Video, in partnership with Grindhouse Films. There’s a 4K disc with the film itself, probably looking better than it did even in theaters (the picture has a rough and ready look that is far from, say, “Lawrence of Arabia,” but befits a pre-prettyfication New York City), and a contemporary interview segment featuring Ahearn, Fab Five Freddy, and Blondie’s Chris Stein, who helped coordinate the movie’s music. To avoid clearance issues, all Hip Hop tracks in this picture were specially composed. Stein helped push rap into the mainstream with, of course, “Rapture,” a hit for his band, which features Debbie Harry name-dropping some architects of the music while reciting some doggerel concerning a man from Mars.

That video doesn’t show up here (it’s easy to find online, though), but honestly, that’s about the ONLY “Wild Style” related thing that you won’t find here. There is a full Blu-ray worth of extras and a CD with the soundtrack, radio spots, and an Ahearn interview.

The set was a passion project for Arrow producer James White, who’s also responsible for some pretty jaw-dropping titles for that label over the past decade and change. (Full disclosure: I sometimes write booklet essays for these packages, including one for “A Few Dollars More.”) In an interview at BluRay.com, he speaks about why he wanted to put this package together: “I first saw ‘Wild Style’ during its theatrical run in late 1983 in Cambridge, MA. I was only 12 years old at the time, but it’s no exaggeration to say that the film had a profound effect on my life from that point on. Sure, I’d had some exposure to hip hop before then (‘Rapper’s Delight,’ ‘The Message,’ etc.), but this film revealed an entire world to me, one that felt both raw and fully formed at the same time.

The young talent on screen was bursting from every frame, creating incredible outlaw art and mind-blowing DIY music. ‘Wild Style’ allowed viewers like me to experience the original hip-hop scene in its truest form, unspoiled by commercialization or success. This was our punk rock. I wrote a short piece in our booklet describing the effect of viewing on me, as it did for so many others at the time. Experiencing the film at that tender age was a gateway drug of sorts, as it sparked an obsession that has never really left me, one that had a profound effect on my subsequent interests in art, music, and cinema.”

“Anyway, given my knowledge and enthusiasm for the film, it made sense for me not only to oversee the restoration but to be the producer of our release as well. It was such a great opportunity that I didn’t foresee any problems with this arrangement, although if I knew the amount of work I was in for, I might have thought differently!”

I’d say the work paid off beautifully.