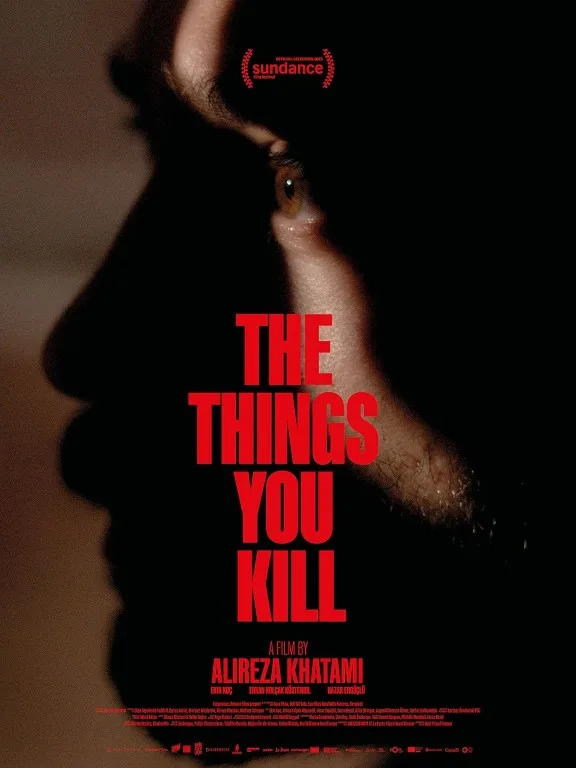

There is uncommon steadiness and control to “The Things You Kill.” The assuredness displayed by Iranian director Alireza Khatami suggests a hunter, gently lining up his target in his scope. He is following a translation professor whose sudden brush with tragedy and his long odds of having a family cause him to dramatically react against his vicious father. When Khatami fires at his protagonist, the aim is true and direct, piercing generational masculine violence, the toll of emasculation, and the pain of otherness with an openness that leaves one quite stunned.

An unnerving character study that often borders on thriller territory, “The Things You Kill” is a psychologically intense piece of genre filmmaking. It is a film about doubles that primarily concerns two characters in two locations that symbolically become one. Tellingly, in fact, this begins with the recounting of a dream. The Turkish-born Ali (Ekin Koç) listens to his wife, Hazar (Hazar Ergüçlü), recall a vision of his father. In her dream, his dad knocks at their door; his face is so exhausted it’s beyond description; he tells Hazar to “kill the lights.” By the end, it’s a nightmare Ali will also experience, but with a grimmer context.

Ali doesn’t know it yet, but he is in turmoil. When he visits his mother, who can only get around the house via her walker, he discovers her toilet is clogged and there’s a gun wrapped in a towel in her septic tank. Upon visiting a fertility clinic, he’s diagnosed with a low sperm count that’ll make the possibility of fathering a child negligible. At his second home, in the desert, he struggles to tend his arid garden.

These threads become tightly intertwined when Ali’s mother passes away. Grief-stricken, he turns his ire toward his apathetic, often menacing father (Ercan Kesal). At Ali’s lowest point, Reza (Erkan Kolçak Köstendil), a gardener, arrives at his desert home promising that he can revive the land. Before long, Reza’s malicious influence is acutely felt, causing the once gentle Ali to not only turn to violence but also to engage in an anger so potent that it quite literally causes Ali to lose his identity.

See, if you squint, Reza and Ali share a passing resemblance. So, it doesn’t take much effort for Reza to chain Ali like a dog at his desert home and take Ali’s place. Unlike Ali, Reza is dangerous and misogynistic, morally corrupt and prone to outbursts. In his taking over of Ali’s life, an earlier scene bears importance: Ali teaches his translation class that the etymology of the word “translation” differs greatly between Latin and Akkadian. In the former language, it means to transfer meaning; in the latter, it can mean to stone or destroy. Through Reza, are we watching a translation of Ali’s true self or his destruction? Are the grisly events we are witnessing—such as the disappearance of Ali’s father—part of reality or the playing out of Ali’s deepest desires?

Khatami and his DP Bartosz Swiniarski (“Apples”) visually demonstrate Ali’s destabilization through long, static takes whose slow push-ins quietly tear apart domestic compositions. There’s the initial recounting of Hazar’s dream, which situates the viewer inside Hazar and Ali’s home as the pair stand outside on their deck, on the other side of a window. The camera pushes toward that window, beyond the dozens of books stacked on the sill, serving as a visual cue that we’re leaving logic behind. Another wonderful push-in occurs later when Ali, sitting in his father’s living room with his family, begins to question the events surrounding his mother’s death. The intergenerational masculine tension between father and son erupts so quickly in such a still environment that you come to wonder how often the pair have come to blows.

Along with these static shots, Khatami and Swiniarski also love leaning on rack focuses to blur Ali’s identity further. Tellingly, Ali studied in the US for fourteen years, so he never quite feels like he’s part of his family or his country. Though he’s his parents’ only son—Ali also has a sister, Nesrin, who often critiques his aloofness—Ali meekly wears that title. Indeed, every visual choice by Khatami and Swiniarski elucidates Ali’s discomfort with the traits that should define him.

If “The Things You Kill” has any drawbacks, they happen when Khatami abandons dramatic ambiguity for thematic literalism. It doesn’t take much effort to connect Ali’s sterile garden with his infertility. Nor does it require much brain power to see how Ali’s turn to brutality is perpetuating the generational trauma his father also experienced. Khatami even throws in a cracked mirror at Ali’s desert home—which, admittedly, does inspire an on-the-nose but visually skillful shot—for good measure. In those moments, you can feel the director over-sharpening his scope to the point of losing focus on the dreamlike atmosphere he’s cultivated.

Thankfully, Koç and Köstendil are two actors so wholly committed to their doubleness that even when the film becomes obvious, they’re still capable of conjuring some sense of mystery. Moreover, the haunting ending, though applied with greater severity and mystique, pulls off a similar trick to Jafar Panahi’s “It Was Just an Accident” by leading one to question whether this protagonist will ever fully wash himself of this psychological stain. Because what is left to kill when part of you already feels dead?