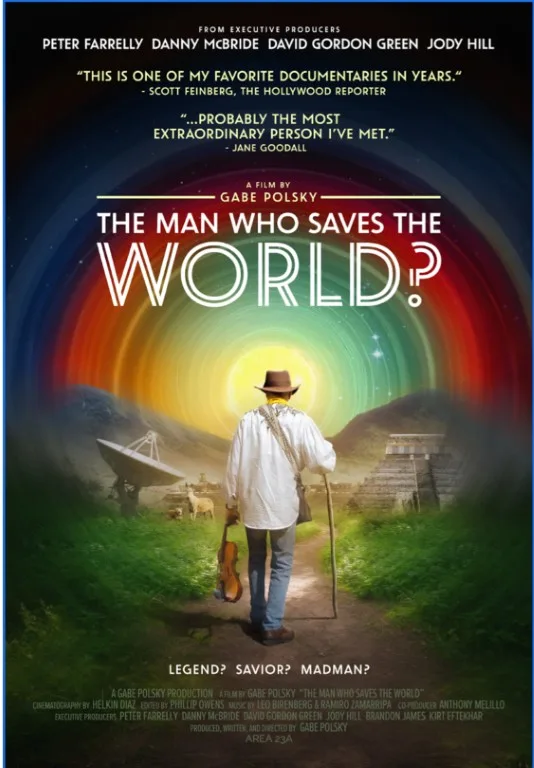

There’s a very interesting moment near the end of Gabe Polsky’s documentary “The Man Who Saves the World?”. Polsky is in Colombia with Patrick McCollum, an award-winning peace activist, who believes he has been chosen by an ancient prophecy to help unite the indigenous tribes of South America to save the Amazon. (In fact, four elders of various tribes told him in person he was “the one” they saw in the prophecy.) After months of bridge-building, the tribes come together for the first time, joined by elders and leaders of the North American tribes. It is an historic gathering. Polsky, who had been following McCollum for months, seems a little worried. Does McCollum really believe all this? Is he some megalomaniac or something? What is this prophecy, anyway? What will it look like? McCollum is irritated by Polsky’s skepticism, but clear in his response. The prophecy foretold that McCollum would bring the tribes together, and look around you: there they all were, together. The prophecy wouldn’t look like heavens opening up. It would look like 150 people gathered in a field. Various elders tell Polsky the same thing. The prophecy was literally happening as they spoke, and Polsky couldn’t see it.

I keep going over this moment in my head. It is connected to the sense I got as I watched McCollum navigate the world. He is a very unexpected sort of person. He started out as a jewelry-maker. He was ordained as an interfaith minister in the ’70s. His list of his “credits” is impressive. He has held high-level positions in international peace organizations and interfaith religious councils. He doesn’t sit in an ivory tower pontificating over what should be done. He’s not a billionaire with grandiose plans. He lives off Social Security, and he’s out there in the jungle, with a deteriorating knee and back, meeting with indigenous elders, doing way more listening than talking. Even when describing the portal he fell into during his near-death experience, or his many UFO sightings, or even his belief in raising global consciousness, he sounds forthright and practical. Not fancy or theoretical. He’s “out there” but he’s connected to the earth.

The late Jane Goodall, who partnered with McCollum on many ecological projects, nominated him to be Messenger of Peace for the United Nations in 2020. She is interviewed for the film, saying at one point, “He’s different from other people. He truly seems to have been put on this planet with a mission.” As McCollum’s knee falls apart, Goodall pleads with him over Zoom to slow down: “You’ve got to get your knee healed. We need you on this planet for a while longer.”

An “endorsement” from Jane Goodall is a tremendous vote of confidence.

“The Man Who Saves the World?” is both a presentation of McCollum’s peace activism, but also Polsky’s sometimes confused responses. Polsky occasionally speaks in voiceover, sharing his contradictory thoughts. “What am I missing?” he questions himself. In these chaotic times where people are feeling grim and hopeless, what to make of this old guy talking as though world peace is possible? What Polsky is witnessing is the painstaking work of organizing. McCollum points out to Polsky that the tribes invited him in. He didn’t declare himself “the one” to fulfill the prophecy.

Polsky follows McCollum on trips to Colombia and Mexico. He stays with McCollum and his wife in Los Angeles, and he travels to New Mexico to see the crazy house McCollum has been building with his own hands in the middle of the desert. The house has a tower, there’s an elevator shaft (no elevator yet), and stairs leading nowhere. Running water is intermittent. Roswell is nearby. (This explains all the UFO sightings.) You get a fuller picture of McCollum the man, as you watch him struggle with pain, or building things, or playing the violin (which he constructed himself). You also watch him decide not to pick up when the activist Mairead Maguire calls, because he’s in the middle of something, he’ll call her right back. Nobel Peace Prize winner or no, she can wait.

A friend told Polsky, who hails from Chicago, about McCollum and the prophecy, thinking Polsky would be fascinated. He was. Polsky got his start producing, alongside his brother Alan Polsky, Werner Herzog’s “Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans.” In 2012, the Polsky brothers co-directed “The Motel Life,” an adaptation of Willy Vlautin’s novel, starring Stephen Dorff, Emile Hirsch, and Dakota Fanning. (I was a huge admirer of “The Motel Life,” which I reviewed for this site. In 2015, I interviewed Alan Polsky onstage at Ebertfest when the film was screened.) “The Motel Life” put the Polskys on my radar.

In 2014 and 2019, respectively, Gabe Polsky directed two documentaries about hockey in Russia. “Red Army” was the story of 1980 “miracle on ice”, as experienced by the Russian players. Polsky, who speaks Russian, interviewed as many members of the 1980 team as he could find. 2019’s “Red Penguins” takes place in an almost forgotten time in Russian history: the brief period between the Soviet Union’s collapse and the rise of the oligarchs. Capitalism flooded into the void, and someone dreamed up a joint venture between the Pittsburgh Penguins and the former Red Army team. “Red Penguins” is a portrait of capitalism run amok in a time of seething political upheaval. “Red Army” and “Red Penguins” would make a great double bill. Polsky’s directorial tone is distinctive. You can tell these films are his. He approaches things with a wry sense of humor and an eye for detail. He is not afraid to incorporate doubt or follow tangents. He is a talented interviewer, unafraid to push back. His style is light-hearted, almost whimsical, with a sharp sense of the absurd. Things are always about to careen out of control. He’s deeply engaged with the subject matter, even if he’s not quite sure what to think.

One could picture another less-creative director making a very different kind of film about McCollum: an earnest, respectful work of hagiography. Polsky includes his doubts, his trip to the ER for dehydration, his worrying that he’s not “getting” it. “The Man Who Saves the World?” is a quest, and sometimes a mad one. At one point, Polsky describes himself as Sancho Panza to McCollum’s Don Quixote, and McCollum laughs with pleasure. He likes that. Polsky is so honest he has to add a question mark to the film’s declarative title. This slight detachment, this hesitation to believe without question, makes Polsky the best of guides.