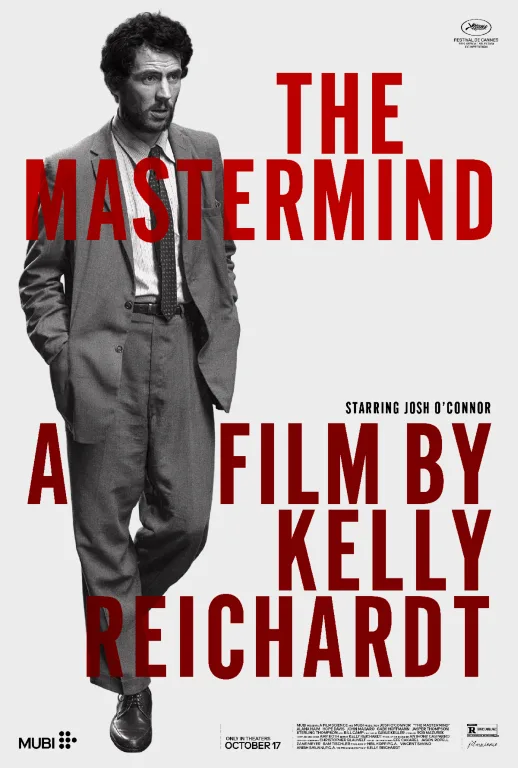

“The Mastermind,” a 1970s-style character portrait of an art thief from writer-director Kelly Reichardt (“Old Joy,” “Meek’s Cutoff,” First Cow”), is perfectly titled. It captures the way the thief sees himself. But it could also be sarcastic—the kind of nickname other prison inmates would give the new guy, who’s behind bars because his estimation of his abilities doesn’t match reality.

Josh O’Connor plays James Blaine Mooney, a married suburban father of two with a secret life as an art thief. Not the Thomas Crown type of art thief; he’s a couple of steps up from somebody who’d steal a rolled-up poster from a booth at a fan convention. James’ wife, Terri (Alana Haim), doesn’t know about her husband’s secret life, only that there are times when he’s supposed to drive the kids home from school but calls to say he can’t because something important just came up. To observers beyond the Mooneys’s little circle in the Massachusetts town where they live, James might be just another handsome, charming but rather slippery young husband who’s been coasting on his unkempt charisma and is going to get cleaned out in divorce court when his wife finally decides she’s had enough.

The movie starts with James stealing one small item from a museum he’s visiting with Terri and their two young sons, Carl (Sterling Thompson) and Tommy (Jasper Thompson), and walking out with it. In the process, he admires some work by Arthur Dove, who some historians consider the first American abstract painter. He also sizes up the museum’s security staff, which isn’t exactly formidable; one of the guards is slumped in his chair, napping. So James assembles a team consisting of himself and two other guys, Guy Hickey (Eli Gelb) and Larry Duffy (Cole Doman), to steal four of the Dove paintings, which James intends to sell to his regular fence. He is adamant about staying outside in the car while the other two carry out the theft, because he and his family spend so much time at the museum that he’d surely be a suspect. (And of course he’s offloading risk, too.)

As in “Dog Day Afternoon,” one of many great 1970s character studies that “The Mastermind” evokes, the team falls apart when one of the other two guys bails out early. James replaces him with Ronnie Gibson (Javion Allen), a tougher, cooler criminal who is also the only Black person associated with James’ scheme. Ronnie is called a “wild card,” which sounds like a euphemism for a more experienced crook who treats a crime as a crime, not as a fun thing for middle-class white guys to do for extra money and an adrenaline rush.

From there, things fall apart, as they always do in heist movies. Like a lot of people, James wants to do a particular thing. He comes up with a pretty good plan but hasn’t given much thought to how to pivot if one of the elements doesn’t go right, and has devoted exactly zero effort to figuring out where his life might go afterward, for good or ill. He seems surprised by subsequent events that anyone could’ve seen coming. The first half of the movie is a slow-burning crime drama about a thief of no importance, while the second half focuses on a man who must escape the wreckage of his former life.

There’s a buried political-historical element to the story as well: “The Mastermind” is set in 1970, when it had become clear to just about everyone that the Vietnam War was a mistake, but the domestic protests against it were being met by angry pushback from reactionaries who considered anyone who fought against the war to be a traitor. There are radio snippets and newspaper headlines about the war, and moments where the tension between hawks and doves spills over into regular life.

The point of all this, I think, is to show that even during the peak years of the conflict, roughly 1966-71, the US occupation of Vietnam didn’t touch the lives of most Americans unless they had a family member who was already in the armed forces or a son old enough to be drafted. The Mooneys are one of those families who have thus far eluded the impact of Vietnam, but they can’t escape it forever. This thread ultimately gets tied up by Reichardt with ingenuity and bleak humor. The ending makes the whole thing retrospectively feel like an adaptation of a short story, more of a sketch than a mural, and very much a film comprised of small moments.

If you go into “The Mastermind” expecting the literal or metaphorical pyrotechnics you’d find in a movie by Michael Mann, Steven Soderbergh, and other masters of the heist flick, you’re going to be disappointed and puzzled. This is a relatively quiet movie that takes its time laying out the plot and introducing the main characters. Reichardt—who also edited the film and has said that she based the story on details from many real-life people and incidents, including the 1972 robbery of an art museum in Worcester, Massachusetts—builds the movie with her characteristic mix of dry humor, incisive psychological details, and elegant, minimalistic visuals. Probably a third of the movie consists of long takes where the camera moves not at all or slowly, prowling around in the spaces that her characters move through. Reichardt treats the art heist mainly as a pretext to probe the character of James Mooney, a soft-spoken hustler who could sell water to a fish, but whose profound selfishness becomes more apparent with each new scene.

“The Mastermind” is part of a subgenre of character studies that were common during the period in which the story is set. O’Connor has deservedly been compared to Elliott Gould, the shaggy-sexy wiseguy lead in many New Hollywood classics of poetic grubbiness, most notably “The Long Goodbye,” Robert Altman’s 1973 deconstruction of the hardboiled detective story. Like Reichardt’s movie, Altman’s is equally indebted to crime fiction tropes and the exhausted narcissism of the “Me Decade,” when the remnants of sixties-style lefty idealism and anti-authoritarianism were beaten out of the populace by police and starved of attention by a media ecosystem that was tired of telling the same story, important as it was.

Like the better films of that movement, “The Mastermind” makes the audience come to it, instead of spoon-feeding everything via spoken dialogue to the point where something that is supposed to be cinema turns into an illustrated podcast. We get details that suggest an origin story, like the fact that James’ dad William Mooney (Bill Camp) is a judge, which implies that James’ criminality might have started out as a rebellion against the status quo that the old man represents; and James’ symbiotic relationship with his mother Sarah (Hope Davis), whose willingness to lend him money even though he’s stiffed her in the past suggests that maybe she worries that she didn’t give him enough love and support as a child and is trying to compensate with cash.

In the end, though, we don’t know exactly what drives James, nor does he. Those who don’t participate in James’ crimes but are affected by them are not interested in explanations anyway. What matters to them is that James is so in thrall to his urges that he gives no thought to others, and must therefore be considered a threat to domestic tranquility.

This is beautifully articulated in a sequence where James takes refuge in the home of an old friend who idolizes him, Fred (the always-excellent John Magaro, who’s like a cinematic good luck charm, given this is his third film in a row with Reichardt); and Fred’s wife Maude (Gaby Hoffman), who, in measured, polite but firm language, tells him he’s not welcome in their home because his presence exposes them to collateral dangers. Fred, of course, won’t talk to him that way, because he sees James as an aspirational figure. (Filling James in on his life, Fred says, “I’ve been substituting at the middle school,” then pauses before adding, “I’ve shaved my beard.”)

I’ll admit here that I was slightly impatient with the movie during the first half, mainly because James’ character seemed too superficial and blatantly manipulative to merit the kind of scrutiny that Reichardt gives him. And there is a case to be made that both James and the movie are doing a convincing impersonation of depth. But it’s a delicate murmur of a movie, and if you tune into its wavelength, it gets funnier and sadder as it goes along. James lies the way other people breathe. He talks to everyone, including his kids, as if they’re accomplices in a crime that’s already in progress, and are expected to adjust to any and all changed circumstances, even though James’ is the one who changed them.

The film might not work if it starred anyone but O’Connor. He’s one of the great recent finds in world cinema, and an actor who seems to be everywhere now, deservedly so. It’s exciting just to watch him sit and think. There’s a shot of him standing in front of a window with the sunlight silhouetting him that sums up the opaque charisma of this man. It’s hard to say if he contains multitudes or just a pack of cigarettes, a can of Budweiser, and a bottomless supply of self-regard. O’Connor is brilliant at playing guys like this, who can’t be trusted but shouldn’t be written off as irredeemable. James Mooney is like one of those old friends you might let stay overnight at your home, even though the last time he did, a couple of things went missing.