Andres Veiel’s rich investigative documentary “Riefenstahl” states the obvious: The infamous German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl was an outright Nazi. But as with any good film, the key isn’t what it’s about but how it’s about it. Given full access to the personal archive of the director who made “Olympia” and “Triumph of the Will,” Veiel builds an overwhelming, indisputable case that not only was Riefenstahl a Nazi, but you also can’t separate the art from this artist’s politics.

For decades, Riefenstahl has floated on a legacy not too dissimilar from D.W. Griffith. Even when some scholars, critics, and programmers acknowledge these filmmakers’ prejudiced outlooks, it’s often followed with a qualifier explaining their form-changing techniques, as if their cinematic importance should negate their harmful imagery. But of course, whether they were actually groundbreaking or not can be disputed. Many of the techniques credited as Griffith’s inventions, for instance, were employed by other filmmakers before him. The same could be said of Riefenstahl, whose films weren’t engaging in new shots, angles, or camera movements, but were merely acting on a grander scale due to their expansive budgets.

By making a film that says there is no complicated legacy to Riefenstahl, Veiel’s uncomplicated approach, supported by Riefenstahl’s own words, is strongly rendered into a direct, inarguable slashing of Riefenstahl’s importance.

Veiel structures his film like a dialogue. Whenever Riefenstahl makes a broad claim, such as there being no antisemitism in “Triumph of the Will,” Veiel rejoinders by pulling up a clip from her own archive that disputes her. These volleys, guided by sharp juxtaposing cuts, can be shocking and illuminating, at once taking us deeper into her psyche and closer to her own supposed truth.

Veiel further illuminates the latter by looking at the drafts of Riefenstahl’s memoir, a project she worked on for a decade. In those pages, she adds and subtracts instances of sexual assault, but consistently retains her rape accusation against tennis champion Otto Froitzheim. Veiel doesn’t question whether these instances of assault and harassment happened. He’s far more interested in how Riefenstahl’s self-editorializing mirrors her desire to create her own reality.

In his cradle-to-grave recounting of her life, Veiel weaves in and out of Riefenstahl’s home movies, audio recordings, and her aforementioned memoir. The three sources give us a read on her parents: the mother who wanted her daughter to achieve the dreams she could not attain, and the abusive father. These figures combined to make an unshakably ambitious woman who pushed herself in an acting career as the heroine in Arthur Fanck’s mountaineer movies, into a director who captured the eye of Hitler. A recorded conversation between Riefenstahl and her elderly childhood friends further reveals the director’s propensity for fabrication in the name of being ahead, even if it was only a matter of who made puberty first.

Recordings of her own phone calls also paint the picture of a woman whose separate reality was actively encouraged. Supporters often contacted her to express their admiration for her as a filmmaker. And while these dispatches aren’t overtly racial or political, one can hear between the lines their Nazi ideology in their voice. Others phone in to agree with her that no one could’ve known about the concentration camps, least of all her. We also, through home movies and personal audio, catch glimpses of her husband Horst Kettner, a man forty years her junior who openly admits that in their marriage, he must always submit to her opinion.

With his incisive documentary, Veiel isn’t claiming to be the first to reveal Riefenstahl’s Nazism. In fact, through archival interviews, particularly one conducted on “Je später der Abend…,” which featured Riefenstahl in conversation with anti-Nazi activist Elfriede Kretschmer, he shows that her politics weren’t a secret. The same could be said about her stage direction instigating a massacre of 30 Jewish men in Końskie, Poland in 1939 or her bringing on Roma and Sinti prisoners from concentration camps to be extras in her film “Lowlands” while knowing they’d be sent to their deaths after filming finished. In fact, many people confronted and denounced her during her lifetime. Instead what’s telling is how many people bought into her fantasy.

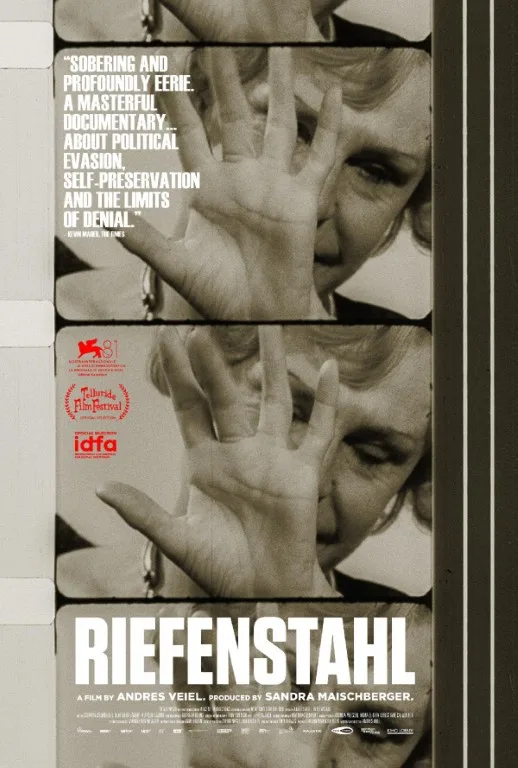

The Telluride Film Festival, where “Riefenstahl” played after its Venice premiere, for instance, honored Riefenstahl in 1974. When asked about the controversy surrounding the festival honoring the Nazi filmmaker, Gloria Swanson shot back, “Why? Is Leni Riefenstahl waving a Nazi flag? I thought Hitler was dead.” Through Veiel’s film, we find that Riefenstahl never stopped waving that flag both publicly and spiritually.

In covering her career beats, Veiel also makes a disturbing thematic connection in the director’s work: her obsession with the human form. Her interest, which one interviewer connects to the Nazi ideology of racial purity, plainly spills out in her film “Olympia,” a 1938 documentary about the Berlin Olympics. But it also surprisingly resurfaces in her exoticizing interest in Black bodies. In “Olympia,” for example, she fixates on Jesse Owens. That isn’t totally surprising; the gold medalist was the star of that event, partially because of his athletic prowess and because his success repudiated Hitler’s (and America’s, for that matter) belief in racial superiority. Riefenstahl, however, openly claims to be transfixed by Owens’s Blackness. That attraction returned with her photography of the Nuba people, where she displayed a colonizer mindset toward what she considered untouched people. It’s an approach that shows how her Nazism remained present, even when she thought she was being progressive.

If there’s one thread that doesn’t necessarily fit, it’s how Veiel nearly opens and closes with a memory of Riefenstahl’s film, “The Blue Light.” He begins the documentary with the Nazi director explaining that she’d like that work to be her legacy, but he spends much of his film steering clear of the subject as though he’s revolting against her wishes to reveal her true legacy. But then he caves, leaving us on the note she wanted. One understands the desire for symmetry, but it’s a tonally odd choice in a film that takes her to task. No matter the decision, it doesn’t erase the film’s central thesis: Riefenstahl was a deluded Nazi sympathizer, not a complicated artistic genius. Like all of Nazism, she was just plain evil.