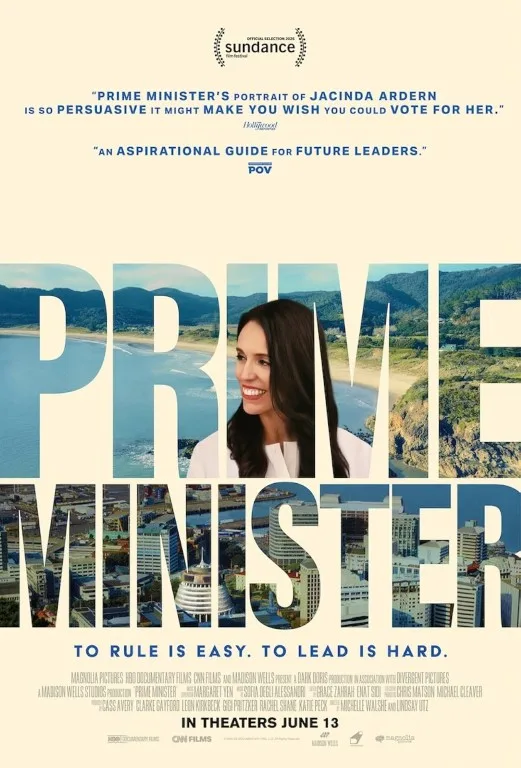

At 37, Jacinda Ardern became the 40th Prime Minister of New Zealand, the youngest female head of government in the world. Shortly after taking office, she gave birth to her first child, only the second time an elected female head of government did so. (Queens don’t count.) Ardern was Prime Minister for five years (2017-2023) during a time of intense upheaval, both globally and nationally (she reiterated in speech after speech how the two are interconnected). There were the devastating mass shootings at the Christchurch Mosque in March 2019, just a year before the world shut down due to COVID-19. Her response to these crises brought her worldwide praise but also vitriol, in equal measure. “Prime Minister,” directed by Lindsay Utz and Michelle Walshe, is an intimate backstage look at those years. In many ways, the documentary is as unprecedented as Ardern’s career.

That all these things are unprecedented is not just a fact, but an embarrassment. It shouldn’t be some weird novelty that a political leader is pregnant. The questions she fielded during her campaign were impertinent and insulting. At the same time, it’s notable that Ardern and her partner, Clarke Gayford, were not married at the time she took office, and being pregnant while unmarried was treated as totally uncontroversial (it’s hard to imagine this happening in the United States). The documentary is frank about Ardern’s struggles. She was determined to breastfeed her baby, but how would that work as Prime Minister? With no roadmap, she had to carve her own path. She was not a political newbie. Ardern had been active in the Labour Party since she was 17 years old and was first elected as an MP in 2008. When the leader of the Labour Party resigned in 2017, seven weeks out from the general election, Ardern was nominated as the new leader. With little time to campaign, Ardern realized, “I could only be myself.”

The documentary is made up of a collage of footage. There’s extant news footage of her press conferences and public appearances. If “Prime Minister” had followed the route of most political documentaries, this footage would have been interspersed with talking-head interviews featuring Ardern, her opponents, her supporters, journalists, and others. But “Prime Minister” is different. Ardern’s partner Clarke took videos of her entire campaign and time in office, including their home life. He asks her questions off-screen, as she lies in bed, hugely pregnant, surrounded by official papers. These are incredible glimpses, unfiltered and raw. She speaks of her “impostor syndrome,” her anxiety as she faced these huge struggles. She reacted with boldness to the various crises facing New Zealand and the world.

Look at New Zealand’s swift reaction to the mass shooting in Christchurch. Ardern’s speeches were filled with unambiguous language: “strongest possible condemnation,” “we utterly reject and condemn …” She talked about the migrants and refugees who “chose to make New Zealand their home,” and the grief the country felt at that trust being betrayed. New Zealand passed strict gun ownership laws with a swiftness shocking to America, where dead schoolchildren were not enough to move the needle. New Zealand instituted a “buy-back” program for gun owners, who voluntarily turned in their assault rifles and automatic weapons. “Fifty people died,” said Ardern in a speech, “They do not have a voice. We are their voice.”

COVID-19 was the game-changer. As the saying goes, it broke a lot of people’s brains. Ardern, with expected boldness, closed New Zealand’s borders, an unpopular choice in many circles, but admired in others. “Prime Minister” stays very close to Ardern. This may be unsatisfactory to those who want a more “balanced” portrait, but as a world leader she intersected with everything affecting all of us. This is not a portrait of a woman in isolation. It’s fascinating to see her 2017 visit to the United Nations. Reporters cluster around her and so many of them ask the same question: “Do you like President Trump?” Not “how do you feel about Trump’s policy of …” but instead the middle-school question, “Do you like him?” “That’s an irrelevant question,” says Ardern, as indeed it is. But then she is asked the question again. “But do you like him, though?” This is the sign of unreality starting to infiltrate the mainstream.

Extremism was on the rise, intensified by Covid isolation, misinformation, and QAnon memes circulating on Facebook. Her final year in office was roiled by controversy, culminating in 2022, with a violent standoff between the police and protesters occupying Parliament grounds, many of whom were waving American flags, oddly enough. One of the protesters referred to her as “some girl in a skirt on a power trip.”

“Prime Minister” includes two separate audio tracks: Ardern speaking for the documentary, and the audio she provided for an Oral History Project started by the Alexander Turnbull Library. We distinguish between the two voice-overs by the quality of the audio, an unnecessarily confusing choice. The lack of outside interviews may strike some as dishonest. But “Prime Minister” is interested in the personal and political journey of one woman, in office during an unprecedented time of change. It doesn’t craft a narrative. Ardern crafts her own narrative.

In September 1787, Philadelphia socialite Elizabeth Willing Powel, playing hostess to many of the delegates in town for the Constitutional Convention, regaled Benjamin Franklin with a question the day after the convention ended: “Well, Doctor, what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?” Famously, Franklin replied, “A republic, if you can keep it.” In a lecture given to Harvard students, Ardern quotes this exchange as a warning that Americans—and everyone who cares about liberty—would do well to remember. Republics are hard to “keep.” Peace and stability are always fragile. Ardern didn’t just observe this truth. She lived it. “Prime Minister” presents a very recent history, and therefore, there is little retrospective philosophizing and almost no nostalgia. Time will tell what all of this will look like in the years to come.