“There was some quiet noise in our home,” Judith Richter says in the documentary “The Last Twins.” Her parents were both Holocaust survivors who were imprisoned in the Auschwitz concentration camp. Richter’s mother was willing to share some of her stories. But there was an understanding that “you don’t ask your father about the Holocaust.” It was not until 1981, when Richter’s husband made an impulse purchase at a grocery store in Boston, that the family and then the world began to hear the story of her father’s heroic protection of the young twins who were horrifically abused and murdered by one of the most savage villains of the 20th century, Josef Mengele. As one of the survivors tells us in “The Last Twins,” “Most mass murderers don’t know their victims. But he knew every one of them because he looked in their eyes before he sent them to death.” And most of them were children.

But this is not a film about Mengele’s horrific “experiments.” We hear some details, particularly from one survivor who tells us Mengele was interested in why his twin had a beautiful singing voice while he did not. Mengele injected pathogens into their throats. The twin died a year after the war ended, and the survivor, whose “raspy” voice was of interest to Mengele, had to have his throat and gullet removed, and now speaks with the help of a mechanical voice box.

But this film is the story of Erno “Zvi” Spiegel, a man who did the best he could in the direst of circumstances. His kindness and the example of his humanity were of crucial importance in giving the boys a sense of the possibility of survival and a life of purpose. And it is the story of the survivors, the lives and the families they created as the best possible refutation of Hitler’s plans.

Spiegel, a twin himself, was 29 years old when he arrived at Auschwitz from his home in Hungary. He was selected to assist Mengele by watching over the twin boys who were going to be examined, experimented on, and then, in most cases, murdered and autopsied. (The twin girls, including Spiegel’s twin, Magda, were in a different facility.)

Spiegel immediately began to do whatever he could to befriend and protect the boys, starting with changing the birth dates of a few non-twin siblings close in age to list them as twins, which kept them from immediately being killed in the crematoriums. He comforted the boys and taught them history, geography, and math. According to a paper about Spiegel by Holocaust scholar Yoav Heller, “One of the ground rules that Spiegel established was that the children had to share with one another any commodity that they possessed, especially food. In addition, he taught them that they had mutual responsibility for the safety of one another.” The survivors, now old men, speak of him in the documentary with tears in their eyes, calling him the closest they had to a father. Spiegel knew it was impossible to save all the boys, but he did not lose hope about saving as many as he could. He lived by the Talmudic teaching that “Whoever saves a single life is considered by scripture to have saved the world.”

At one point, a Nazi doctor named Heinz Thilo told the boys to line up so he could send them to be killed. Spiegel risked his own life to insist on speaking to Mengele, who overruled Thilo’s orders.

After the Russian army liberated the camp, Spiegel stayed with the surviving boys and took them to safety in Hungary. He met a fellow survivor, and they got married and moved to Israel. Spiegel became CFO of a theater group, a job he loved, considering it “a gift from destiny.”

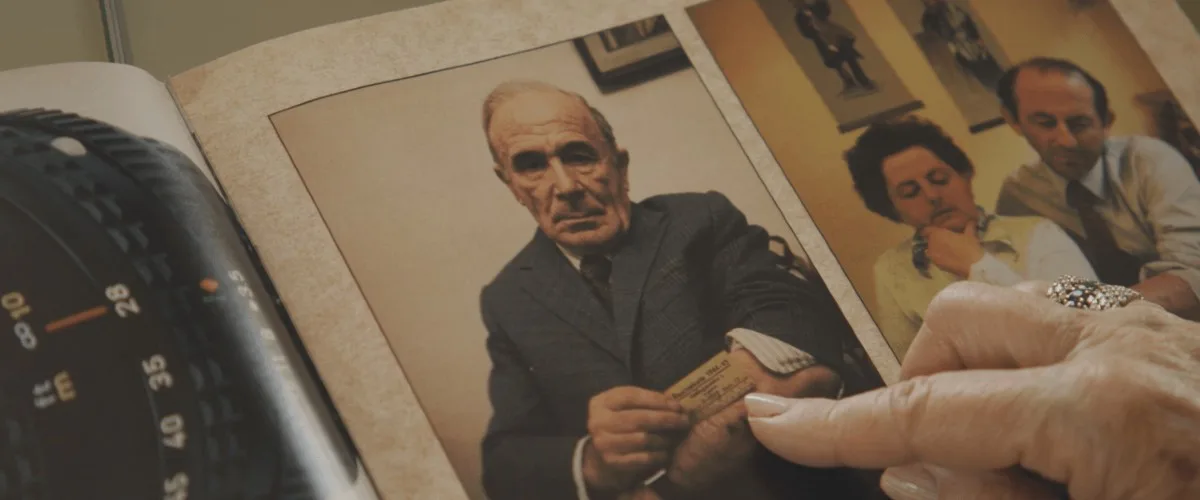

And then, in 1981, Spiegel’s son-in-law was in the checkout line of a grocery store and picked up LIFE Magazine because he was interested in the picture of planets on the cover. Inside, there was a story about Mengele, with a photograph of Spiegel and a story no one in the family knew anything about. Some of the surviving twins saw the story, too, and reached out to be reconnected with the man they credit with saving their lives.

The scenes of the reunions are deeply moving, especially when the surviving twins participate in the bar mitzvah ceremonies they missed when they were imprisoned. Richter tells us that when she was growing up in Israel, there was no special recognition of Holocaust survivors. There was so little information about what happened that the general impression was of passive Jews who allowed themselves to be herded into gas chambers. It was not until stories like Spiegel’s and the trial in absentia of the never-captured Mengele (we see some footage of the event here) that the survivors were recognized for their courage and resistance.

The documentary features some archival footage, but its power lies in the vivid, heartfelt interviews with the surviving twins and Richter and her husband, who respond to sensitive and sympathetic questions from filmmakers Perri Peltz and Matthew O’Neill. Its power is also in its message: That the ultimate refutation of the Nazi’s efforts to exterminate people they considered “subhuman” is the lives of love, contribution, and meaning exemplified by the survivors.