Where did “My Beautiful Laundrette” come from? Thirty years after it was made, and a few weeks after it was released on Blu-ray by The Criterion Collection, the film seems as miraculous as it did in 1985. On one level, that question’s easy to answer: it’s a collaboration between director Stephen Frears and screenwriter Hanif Kureishi. While Frears had made a few films intended for cinema release, most of his work consisted of made-for-TV movies. Critic Dave Kehr once attacked Frears by pointing to his TV background, but British TV of the ’70s and early ’80s had room for such radical talents as Mike Leigh and Alan Clarke. (Indeed, Clarke’s made-for-TV version of “Scum” bests his theatrical version.) “My Beautiful Laundrette” was made with TV in mind, shot in the then-cheaper format of 16mm, but the response it received at film festivals quickly proved that it warranted a theatrical release.

At the time, Kureishi was known for a few plays about the South Asian-British experience. He spent some time researching Pakistani and Indian-owned laundromats, putting it into “My Beautiful Laundrette.” In 1985, British films with South Asian protagonists were rare. Graham Fuller’s liner notes for Criterion’s disc reel off a list of South Asian-British filmmakers currently working, but I didn’t recognize half their names; it seems that much of this work still hasn’t crossed the Atlantic. (Perhaps it’s a mirror image of the difficulties Justin Simien’s “Dear White People” faced finding distribution in the U.K.) As far as I know, Kureishi is heterosexual, but he uses gayness as a battering ram against the prejudices of Thatcher’s England, as well as the narrow-mindedness of his own diaspora. In 1985, New Queer Cinema was still more than five years away. Temporally, “My Beautiful Laundrette” stands midway between the insults of William Friedkin’s “Cruising” and Todd Haynes’ layered AIDS allegory “Poison.” It has few companions: perhaps Bill Sherwood’s “Parting Glances” and some of Derek Jarman’s work, although Jarman was generally more formally adventurous.

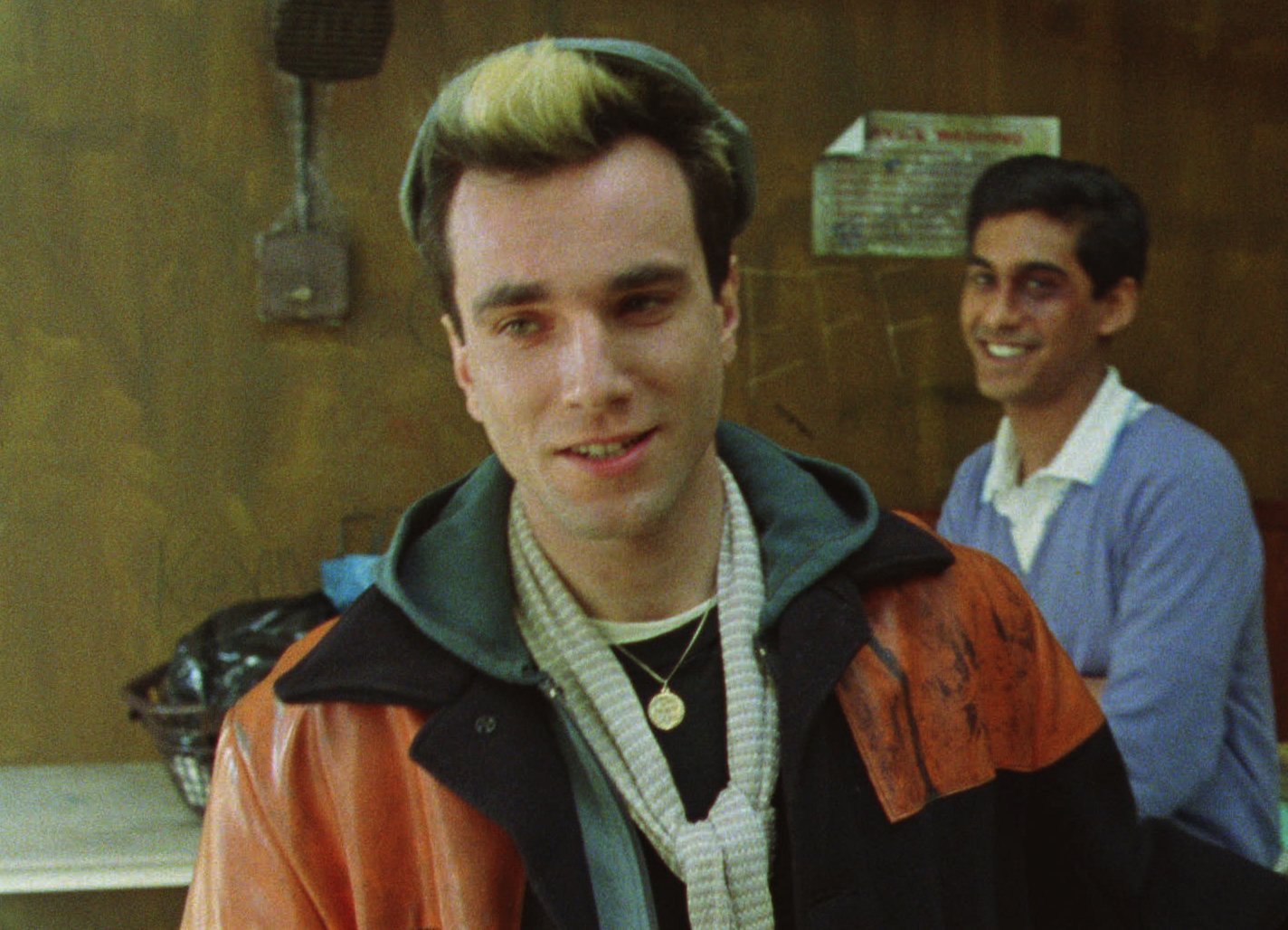

The film begins with racist punk Johnny (Daniel Day-Lewis), but quickly shifts focus to the family of Omar (Gordon Warnecke). Omar’s father Hussein (Roshan Seth) is a Pakistani immigrant. He watches the burgeoning far-right National Front movement, to which Johnny belongs, and the general conservative turn in British politics with dismay. Stuck in bed all day, where he likes to spend his time drinking, he wants Omar to take care of him. But Omar has absorbed some of the prevailing Thatcherite current and wants to succeed in business, especially under the tutelage of his more right-wing uncle Nasser (Saeed Jaffrey.) He has ambitions to open a deluxe laundromat. While all this happens, Omar reconnects with Johnny, who quickly throws off his neo-Nazi trappings and becomes his lover. Together, they manage to open their beautiful launderette.

Frears’ background in TV is evident from his reliance on close-ups and two-shots, with the actors’ faces and important objects close to the camera. “My Beautiful Laundrette” plays well on the small screen. However, it also transcends it. It uses color in particularly expressive ways. Frears was also a product of his times. The neon lighting and cinematography aren’t a million miles away from Michael Mann’s “Thief” and Tony Scott’s “The Hunger,” even if “My Beautiful Laundrette” never comes close to announcing itself as an exercise in style the way those films do. The settings are often bathed in blue light, and other primary colors pop up as well. On the day of the laundrette’s opening, it’s filled with sunny yellow lighting. This may be social realism, but it’s anything but grimy.

One can sense Daniel Day-Lewis tamping down his natural charisma. An alternate possibility is that he just hadn’t grown into it yet. Whatever the case, the young actor is convincing as a tough guy trying to reform and a working-class man accepting his fate. His dyed blonde hair, which barely covers a mound of his natural dark hair, marks the times and his character’s punk roots. The middle-aged Day-Lewis seems to play authority figures with an effortless gravitas. Looks aside, the Orson Welles of “Citizen Kane” and “Touch of Evil” is his model. It’s a long way from Johnny to Abraham Lincoln, but Day-Lewis’ performance here is all the more astonishing knowing that he would make the journey.

The film’s portrayal of the punk scene is far from flattering. Most Americans associate British punk with left-wing politics: explicitly anti-racist songs like the Clash’s “White Man in Hammersmith Palais” and concerts held by the Rock Against Racism organization. It may seem particularly odd that a gay man would associate with the National Front (although the organization is never cited by name in “My Beautiful Laundrette.”) However, there’s a real-life parallel: Nicky Crane. Crane posed on the cover of an Oi! compilation (which was withdrawn when it became clear that his Nazi tattoos were visible) and worked with the infamous “white power” band Skrewdriver, yet when he wasn’t in jail, he also worked as a doorman at the gay club Heaven. He came out on British TV in the early ’90s, renouncing racism, shortly before dying of AIDS.

On the other hand, the Pakistani-British community depicted in “My Beautiful Laundrette” is diverse. Both leftists, yearning for the days when Marxism held sway, and aspiring business people are represented. Kureishi and Frears seem to respect the former but recognize that the latter are the wave of the future. The older Pakistani men are also conservative in their sexual politics, keeping white women as mistresses and wanting their daughters to stay home. Johnny and Omar keep their relationship a secret to the film’s end, although they do kiss in front of the laundrette’s window.

One might expect a great career from both Frears, who was in his early 40s when he made “My Beautiful Laundrette,” and Kureishi, who was 31. Instead, things haven’t worked out so well for either artist. They made one more excellent film together, “Sammy and Rosie Get Laid.” Frears’ work remained strong through the ’80s, but after that, he became the victim of his increasingly erratic taste in scripts. His most successful film since that era, “The Queen,” arguably betrays the values expressed in his best films. Kureishi became a prolific author of screenplays, essays and novels, but his work as a novelist may have surpassed his scripts. He never found another collaborator with the same feel for his work as Frears. “My Beautiful Laundrette” is a great film. It’s also a testament to promise unfulfilled.