Is “Room 237” some kind of crazy joke? Rick Ascher’s much-discussed “subjective documentary” features five people who present their theories/interpretations of the “hidden meanings” they say they’ve found in the rooms and corridors of Stanley Kubrick‘s Overlook Hotel, the setting of his chilly 1980 horror film, “The Shining.” I’m asking a question; I don’t know the answer. I haven’t yet had the opportunity to see the picture, which has played a number of festivals (Sundance, Cannes, Toronto, NY, London, Karlovy Vary) and has been picked up by IFC Films and is slated for release in 2013. I have seen Ascher’s 2010 short, “The S from Hell,” however, which the “Room 237” web site says “in many ways laid the groundwork” for the new film. That one is satire.

The premise of “The S from Hell” is that three interviewees — David Legget, John S. Flack, Jr., and Keri Maijala — were traumatized as children by the Screen Gems logo that appeared at the end of TV shows like Betwitched, I Dream of Jeannie, The Flying Nun, The Monkees and The Partridge Family. The innocuous logo is presented as deeply creepy (“the scariest corporate symbol in history,” according to the movie’s web site) and the movie uses all manner of sinister effects to create an aura of menace, like a ghost story or a political attack ad. The point seems to be that those techniques (portentous narration, ominous music, distorted lenses) can make even the most benign of subjects, like an animated graphic, seem chilling. The aim, as the site describes it, is to “make the audience feel the same fear and confusion as the children who were first confronted by the vexing, unfolding sights and mournful, dissonant sounds that hid in the cracks between their favorite TV shows.”

Which sounds not terribly unlike the premise of “Room 237.”

Here’s the actual, unadorned Screen Gems logo from 1965:

And here’s Ascher’s full, nine-minute short, “The S from Hell”:

The S From Hell from Rodney Ascher on Vimeo.

In some ways, you could see this as kind of the flip side of something like the celebrated 2006 fake trailer, re-casting “The Shining” as a gentle family comedy:

The difference, of course, is that the narration, editing and music here transform footage from Kubrick’s film into something cute and cuddly instead of horrific. Flip the coin again and you have this phony serial-killer trailer for “Uncle Buck“:

In anticipation of seeing “Room 237,” I did a little research, consulting the movie’s primary sources on the web, and inspired by early critical reactions from Jonathan Rosenbaum and Girish Shambu, who saw “Room 237” in Toronto and have raised issues independent of the film itself. They hated the movie, not just for how it may or may not misrepresent “The Shining” but for how it distorts the meaning and practice of criticism itself. So, while I can’t venture a personal opinion as to how “Room 237” handles its material, we can look at some of the theories, while acknowledging that certain critical principles stand on their own. So, Girish writes:

Spotting hidden references to the Holocaust or to the genocide of Native Americans is not in itself a critically or politically reflective activity. “The Shining” (while being a wonderful film, for many reasons) simply does not engage with these weighty historical traumas. It is not “about” them in any meaningful way. And neither does it have to be in order to be a great film. But when “Room 237” represents film analysis in a manner that treats it as little more than a clever puzzle-solving exercise, it gives no hint as to the social value and political/aesthetic worth of this public activity. It never intuits what is truly at stake in the activity of paying close, analytical attention to films.

I think what Girish is getting at here is: At what point does “criticism” (observing, analyzing, interpreting what you see in a movie) become something more akin to “conspiracy theory”? It’s a good question. Some people approach movies as as if they were brain-teaser games or riddles designed to be decoded and “solved,” closed systems in which finding “meaning” becomes a simple matter of detecting patterns and deciphering internal rules. You can see this at work by comparing the two contrasting versions of “Donnie Darko“: the original release in 2001 and the Director’s Cut in 2004. In the latter, all the laws of the movie’s ostensible time-travel physics are explained, but the effect is reductive, stripping away the ambiguity (and the resonance along with it) that made “Donnie Darko” a good movie to begin with. (Similarly, “Inception” was conceived as a kind of video game puzzle-movie. But if positing internally consistent fantasy rules for the made-up field of dream architecture is all there is to it, if there is no larger metaphor at play, then what?)

You may be thinking: But, Jim, you have put forward subtextual, close readings of quite a few movies — such as “Donnie Darko” (as the story of a boy who can’t face his incestuous feelings about his sister), “Birth” (as a feature-length riff on themes and images from “Un Chien Andalou“), “Barry Lyndon (as an investigation of fate, chance, free will and the nature of art), “No Country for Old Men” (concerning the lot of human beings, living with the ever-present awareness of death), and even ” Argo” (as a movie about turning incidents into stories and stories into movies)… But I don’t propose that the movies can be reduced to or summarized exclusively in those terms. And they don’t extrapolate from trivial patterns or coincidences, like the old Lincoln-Kennedy meme. (Wow, presidents Lincoln and Kennedy both had vice presidents named Johnson! And they were both assassinated — one in 1863 and the other in 1963! [Except that they weren’t — Lincoln died in 1865. Details!])

One of the “Room 237” theorists is the British historian Geoffrey Cocks. According to a piece in Tablet Magazine:

For Cocks, whom I chatted with this morning, “The Shining” is the Holocaust film that Kubrick, who grew up in a Jewish Bronx household in the 1930s (his father was born Jacob but Anglicized it to Jack–the name of Jack Nicholson’s deranged protagonist), always wanted to make but felt that, for aesthetic reasons, he could never make except in the most oblique possible manner.

The [New York Times] highlights the prevalence of the number 42 in the film –Danny, Jack and Wendy’s son, wears a t-shirt with the number on it; Wendy takes 42 swings of her baseball bat at Jack — and notes that since the early ’70s, that number was seen as an ominous metonym for the Final Solution, which was launched in 1942. (The number was prominent in the ’70s also as the answer to Douglas Adams’ question.) But there’s more.

For example: Jack’s typewriter. Cocks explained to me that it’s an Adler Eagle typewriter–“a German machine, pictured almost to make it a character, a clear representation of the bureaucratic killing machine.” (It’s also the model typewriter Kubrick himself used.) When Jack awakes from a dream in which he has killed his wife and his son, he is slumped over his desk, next to his typewriter, which has changed color. It is now light blue: a color that, according to Cocks, invariably signifies “a system of cold, mighty hierarchical power” in Kubrick’s films….

OK, and where does that get you? (Also: “Eagle” was the name of the Apollo 11 lunar landing module… oh, wait, that’s from somebody else’s theory.) If “The Shining” is “about” the Holocaust, how does that enrich understanding of the film — or, for that matter, the Holocaust itself? What is the movie suggesting by invoking the Holocaust? That Nazis are like murderous (or redrumous) fathers who fancy themselves writers but can’t write? (Hey, maybe it’s a movie about how if Hitler had been more successful as an artist the Holocaust might never have happened!)

It’s not enough to point out that you’ve spotted the number 42 in various places (“Hey, that’s ‘The Summer of ’42’ on the TV!”) without explaining how it is used meaningfully within the movie. On the other hand, we overhear the sound of Road Runner cartoons on TV (“Road Runner, the Coyote’s after you / Road Runner, if he catches you you’re through!”) and you might well want to show how the movie sometimes playfully resembles a live-action Road Runner Looney Tune — especially in the chase through the hedge maze at the end. (If Jack — the name of Cocks’s father! — catches Danny, the boy is through!) Does that make it a movie about a long-legged bird native to the American southwest? Not, as Girish says, in any meaningful way.*

(You may read more of the theories and analyses by the interview subjects — or, what one of them calls “featured obsessives” — of “Room 237” by following these links: Bill Blakemore, Geoffrey Cocks, Juli Kearns, John Fell Ryan, Jay Weidner.)

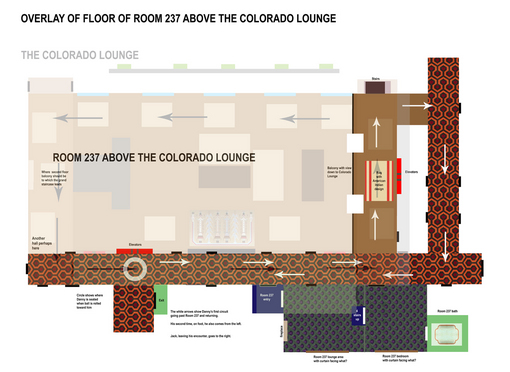

(map by Juli Kearns)

There’s nothing at all wrong with loving a movie and wanting to climb into it, play around in it, explore it, as if it were… I don’t know, maybe a big ol’ empty hotel with many rooms, compartments, corridors, doors, portals, staircases, ghosts, secrets. But, as Girish notes, that’s not criticism, which requires more thorough, disciplined analysis and interpretation. The makers of “Room 237” say they didn’t want to take sides, to evaluate or venture opinions about which theories they thought were valid and which weren’t. I can understand that. They didn’t want to play favorites. However, Jonathan Rosenbaum writes, the unwillingness to evaluate the relative merits of the material they present, creates a problem:

Thus we’re told, in swift succession, that “The Shining” is basically about the genocide of Native Americans, the Holocaust, Kubrick’s apology for having allegedly faked all the Apollo moon-landing footage, the Outlook Hotel’s “impossible” architecture, and/or Kubrick’s contemplation of his own boredom and/or genius. Images from the movie and/or digital alterations of same are made to verify or ridicule these various premises, or maybe both, and past a certain point it no longer matters which of these possibilities are more operative. Unlike his five experts, Ascher won’t take the risk of being wrong himself by behaving like a critic and making comparative judgments about any of the arguments or positions shown, so he inevitably winds up undermining criticism itself by making it all seem like a disreputable, absurd activity. We can’t even tell if he’s representing his commentators fairly; he seems so invested in giving them all equal credibility that he can only make them all into cranks.

If you read some of the pieces I link to in this post, you’ll see that certain of the “obsessives” are more serious (or deserve to be taken more seriously) than others. I mean, it’s perfectly valid to make note that the Outlook Hotel is located on an “Indian Burial Ground” (a familiar horror-movie device: so was the housing development in “Poltergeist“) and that the lobby is decorated in Native American motifs and that the Calumet Baking Powder cans in the pantry are prominently displayed. (And Tang is what the astronauts drink!) Because… well, there they are — you can hardly miss ’em. So, you could make a legitimate case, as Blakeman does. for a subtext involving the ghosts of slaughtered Native Americans (even though they don’t appear as Native Americans but as decadent white aristocrats) exacting their revenge on the red-white-and-blue Caucasian family. But what does “The Shining” do with all those things? That’s the domain of real criticism.

Ascher says “Room 237” began when he and producer Tim Kirk saw some clips on YouTube — including this one, by Jay Weidner: “ Kubrick’s SHINING Analysis – What he wanted us to Know – The Fake Moon Landings” (watch below or read a transcript here):

So, for example, once you spot the Apollo references, how do you use them to corroborate the story that “2001: A Space Odyssey” was Kubrick’s “rehearsal” for faking the moon landing in 1969, as Weidner does in his piece above (subtitled: ” How Faking the Moon Landings Nearly Cost Stanley Kubrick His Marriage and His Life)? And how do you get from there to the threats to Kubrick’s marriage and life? Here’s an example of Weidner’s logic:

Danny is literally carrying a symbolic Apollo 11, on his body, via the sweater, to the Moon as he walks over to room 237. Why do I think this? Because the average distance from the Earth to the Moon is 237,000 miles. The real truth is that this movie is really about the deal that Stanley Kubrick made with the Manager of the Overlook Hotel (America). This deal was to get Kubrick to re-create, in other words, to fake, the Apollo 11 Moon landing.

I’m not sure I agree with you a hundred percent on your analytical work, there, Jay. There’s a real danger of getting lost, as if in the Overlook itself, when you go searching for details just so you can plug them into your existing hypotheses. (Also, there’s this: “The Timberline Lodge [exterior stand-in for the Overlook at Mt. Hood, OR] requested Kubrick change the number of the sinister Room 217 of King’s novel to 237, so customers would not avoid the real Room 217.”) And there’s this comment left on Kearns’ site:

I am interested in your comments on “the dart board” and reversed “237.” Note that the interstitial numbers, “17” and “19,” are both prime. The sum of these terms is “36.” This number is interesting as the square of “6,” as a rebus for “three of 6” or “666,” and because of the fact that all of the terms from “1” through “36” equal “666.”

It’s always exciting and gratifying to discover a fresh angle or a novel interpretation of a familiar movie, but as Rosenbaum says, art is not about secret decoder rings, Rosetta Stones and skeleton keys:

The puzzle aspect of “Last Year at Marienbad” and “Certified Copy” may finally be the least interesting thing about them, but it’s probably the most interesting and important thing about a cynical piece of non-art like “Memento,” which is possibly what makes that film such a cherished cult item and fetish object in certain Anglo-American circles. One way of removing the threat and challenge of art is reducing it to a form of problem-solving that believes in single, Eureka-style solutions. If works of art are perceived as safes to be cracked or as locks that open only to skeleton keys, their expressive powers are virtually limited to banal pronouncements of overt or covert meanings — the notion that art is supposed to say something as opposed to do something.

Which takes us back around to that idea that Roger Ebert has phrased as: “A movie is not about what it is about. It is about how it is about it.” Same goes for criticism.

Let me conclude by quoting the most influential piece on “The Shining,” Richard T. Jameson’s July-August 1980 Film Comment cover story, which helped spark a critical re-evaluation of a Razzie-nominated, Oscar-ignored movie that was not initially well-received. Jameson doesn’t pretend to have any particular key to a movie designed to be frustrating (“The Stephen King origins and haunted-house conventions notwithstanding, the director is so little interested in the genre for its own sake that he hasn’t even systematically subverted it so much as displaced it with a genre all his own.”). He explores how the movie moves — because, after all, “How it feels is how it works.” Take those low-angle tracking shots that follow Danny on his Big Wheel through the hallways:

Yet even as we get off on this wonderful movement, we look for it to disclose more. Will the kid round a corner and run smack into a ghost? Every turn, every new avenue of perception, is approached with anticipation; and nothing happens. Anticipation, anticlimax, anticipation. It has a lot to do with the quality of the Torrances’ lives.

For Jack Torrance’s life has nowhere to go. The wrinkle in Kubrick’s haunted-house concept is not that The Overlook Hotel, with its layer on layer of sordid, largely silly (in Kubrick’s selection from King) atrocity, taints Jack — it is the setting he was born to occupy, the snow-walled zone in which he can achieve an apotheosis he is clearly unequipped to achieve in any other way. To be a writer, for instance, is not within Jack’s grasp. It is sufficient self-justification that his former wage-earning job of schoolteaching got in the way of his writing; or that his wife Wendy so little comprehends the reality of writing (she thinks he just needs to get into the habit of doing it every day) that he can stay points ahead simply by being more sophisticated on the subject than she. The Overlook’s spaces mirror Jack’s bankruptcy. The sterility of its vastness, the spaces that proliferate yet really connect with each other in a continuum that encloses rather than releases, frustrates rather than liberates — all this becomes an extension of his own barrenness of mind and spirit.

Those spaces draw Jack. Kubrick sees to it that they draw us as well. It’s not merely a matter of corridors obsessively tracked. Virtually every shot in the film (whether the setting be The Overlook or not) is built around a central hole, a vacancy, a tear in the membrane of reality: a door that would lead us down another hallway, a panel of bright color that somehow seems more permeable than the surrounding dark tones, an infinite white glow behind a central closeup face, a mirror, a TV screen … a photograph. From the moment [in the opening shot] we lose the consoling sense of focus and destination supplied by that island picturesquely centered in the lake, we are careening through space….

The makers of “Room 237” say they avoided interviewing anyone associated with the making of “The Shining” because that’s not what their movie is about. They wanted to look at the process a movie goes through once it’s finished and goes out into the world. At that point, it belongs to everybody, and is not limited to (or by) the makers’ intentions. In a 1987 interview with Rolling Stone, Kubrick said he hated being asked to explain what his own movies mean. That’s a job for somebody else:

And that’s almost impossible to answer, especially when you’ve been so deeply inside the film for so long. Some people demand a five-line capsule summary. Something you’d read in a magazine. They want you to say, “This is the story of the duality of man and the duplicity of governments.”… I hear people try to do it — give the five-line summary — but if a film has any substance or subtlety, whatever you say is never complete, it’s usually wrong, and it’s necessarily simplistic: truth is too multifaceted to be contained in a five-line summary.

I’m not saying that anyone here is guilty of reducing “The Shining” to “a five-line summary.” But never forget that criticism, above all, demands that you read it critically.

– – – – –

* Here’s Richard T. Jameson on the Road Runner references:

Nevertheless, the tracking in “The Shining” is consecrated to a good deal more than satisfying the director’s lust for technology, or providing a grand tour of a Napoleonically lavish set. It personifies space, analyzes potentiality in spatial terms, maps the conditions of expectations within a neo-Gothic environment that is finite, however imposing its scale. And if this sounds like an arid exercise to pass off as a popular entertainment, consider that Kubrick twice provides the formal nudge of Roadrunner cartoons heard playing on a television offscreen somewhere. Tell a filmgoer that he’s caught between comic and emotional hysteria because Wile E. Coyote’s multifariously misfired stratagems describe a systematic reinterpretation of spatial and temporal possibility, the trading-off of kinetic and potential energy, and he’ll think you’re pulling his chain; but that’s still why he’s laughing.

POSTSCRIPT: Sharp-eyed readers will notice that the title of this post refers to a “keycard” and the Overlook Hotel did not use keycards, but real keys!!! Yes. Because “The Shining” is a movie about slipping backwards and forwards in time, and that headline was written in the future, when keycards were (are?) much more commonplace!

(from TheOverlookHotel.com)

Post-screening Q&A with director Rodney Ascher and producer Tim Kirk at the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival: