Neil LaBute’s “Your Friends and Neighbors” is a film about monstrous selfishness–about people whose minds are focused exclusively on their own needs. They use the language of sharing and caring when it suits them, but only to their own ends. Here is the most revealing exchange in the film: Are you, like, a good person? Hey! I’m eating lunch! The movie looks at sexual behavior with a sharp, unforgiving cynicism. And yet it’s not really about sex. It’s about power, about forcing your will on another, about having what you want when you want it. Sex is only the medium of exchange. LaBute is merciless. His previous film, “In the Company of Men,” was about two men who play a cruel trick on a woman. In this film, the trick is played on all the characters, by the society that raised and surrounded them. They’ve been emotionally short-changed and will never hear a lot of the notes on the human piano.

LaBute’s “Your Friends and Neighbors” is to “In the Company of Men” as Quentin Tarantino’s “Pulp Fiction” was to “Reservoir Dogs.” In both cases, the second film reveals the full scope of the talent, and the director, given greater resources, paints what he earlier sketched. In LaBute’s world, the characters are deeply wounded and resentful, they are locked onto their own egos, they are like infants for which everything is either me! or mine! Sometimes this can be very funny–for the audience, not for them.

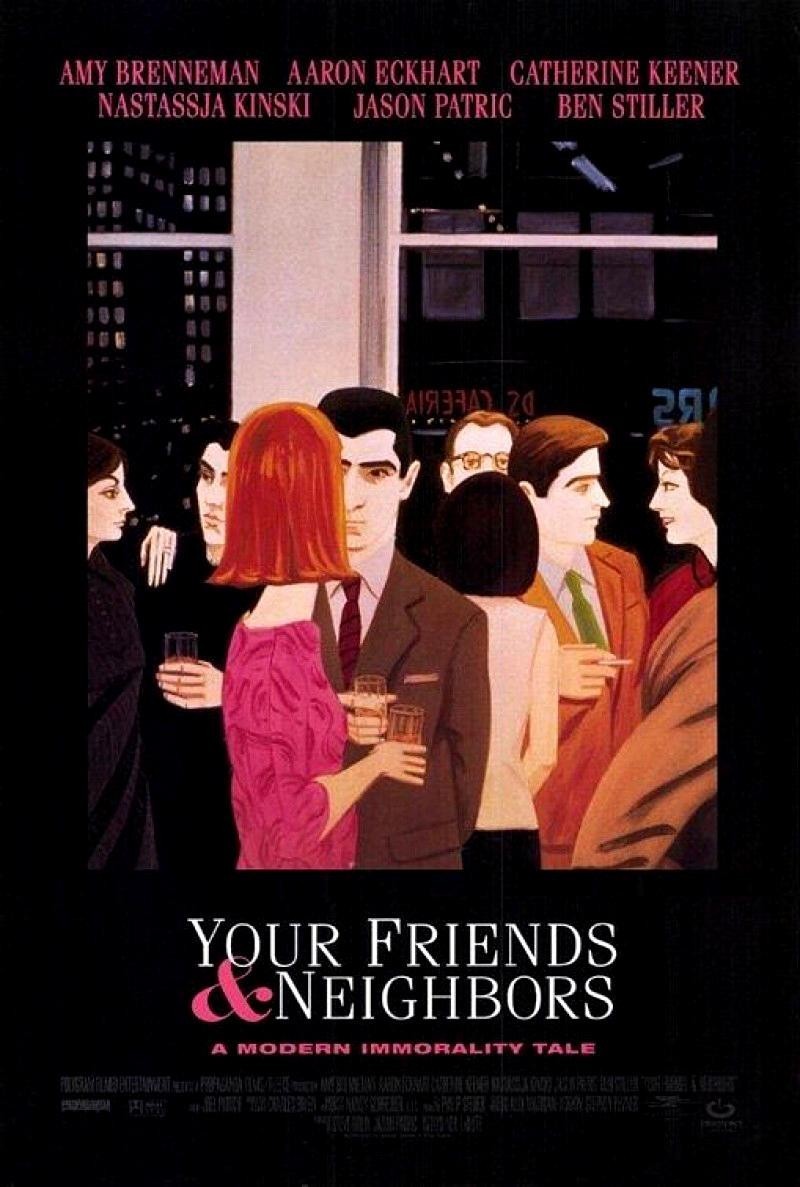

Of course they have fashionable exteriors. They live in good “spaces,” they have good jobs, they eat in trendy restaurants and are well dressed. They look good. They know that. And yet there is some kind of a wall closing them off from one another. Early in the film, the character played by Aaron Eckhart frankly confesses that he is his own favorite sexual partner. A character played by Catherine Keener can’t stand it when her partner (Ben Stiller) talks during sex, and later, after sex with Nastassja Kinski, when she’s asked, “What did you like the best?” she replies, “I liked the silence best.” Ben Stiller and Keener are a couple; Eckhart and Amy Brenneman are a couple. In addition to Kinski, who works as an artist’s assistant, there is another single character, played by Jason Patric. During the course of the movie these people will cheat on and with one another in various ways.

A plot summary, describing who does what and with whom, would be pointless. The underlying truth is that no one cares for or about anybody else very much, and all of the fooling around is just an exercise in selfishness.

The other day I spent a long time looking at the penguins in the Shedd Aquarium. Every once in a while two of them would square off into a squawking fit over which rock they were entitled to stand on. Big deal. Meanwhile, they’re helpless captives inside a system that has cut them off from their full natures, and they don’t even know it. Same thing in this movie.

LaBute, who writes and directs, is an intriguing new talent. His emphasis is on writing: As a director, he is functional, straightforward and uncluttered. As a writer, he composes dialogue that can be funny, heartless and satirical, all at once. He doesn’t insist on the funny moments, because they might distort the tone, but they’re fine, as when the Keener character tells Kinski she’s a writer–”if you read the sides of a tampon box.” She writes ad copy, in other words. Later, in a store, Kinski reads the sides of a tampon box and asks, “Did you write this?” It’s like she’s picking up an author’s latest volume in a bookstore, although in this case the medium is carefully chosen.

The Jason Patric character, too, makes his living off the physical expression of sex: He’s possibly a gynecologist (that’s hinted, but left vague). The Eckhart character, who pleasures himself as no other person can, is cheating on his wife with … himself, and he likes the look of his lover. The Brenneman character is enraged to be treated like an object by her new lover, but of course is treated like one by Eckhart, her husband. And treats him like one. Only the Kinski character seems adrift, as if she wants to be nice and is a little puzzled that Keener can’t seem to receive on that frequency.

LaBute deliberately isolates these characters from identification with any particular city, so we can’t categorize them and distance ourselves with an easy statement like, “Look at how they behave in Los Angeles.” They live in a generic, affluent America. There are no exteriors in the movie. The interiors are modern homes, restaurants, exercise clubs, offices, bedrooms, book stores. These people are not someone else. In the immortal words of Pogo, “We have met the enemy, and he is us.” This is a movie with the impact of the original stage production of Edward Albee’s “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf.” It has a similar form, but is more cruel and unforgiving than “Carnal Knowledge.” Mamet has written some stuff like this. It contains hardly any nudity and no physical violence, but the MPAA at first slapped it with an NC-17 rating, perhaps in an oblique tribute to its power (on appeal, it got an R). It’s the kind of date movie that makes you want to go home alone.