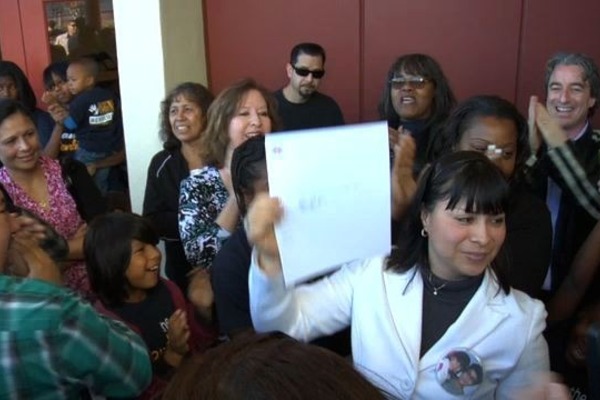

An illuminating moment occurs early on in “We the Parents,” a new documentary directed by James Takata about the first parents in California to utilize the new “Parent Trigger” Law, wherein if parents in a failing school district get enough signatures on a petition, they can request that their local school either close down or become a charter school. In December 2010, a group of parents in Compton, in southern Los Angeles County, presented a petition to Karen Frison, the Superintendent of that district. A swarm of news cameras and reporters push in on the two main figures “starring” in this historic moment. As she hands it over, the parent presenting the petition, visibly nervous, says, “Because we care about our kids.” Ms. Frison replies, kind but firm, “We care about your kids, too.”

In that one simple exchange, the complexity of education reform is laid bare. “We the Parents” is pretty slight (only an hour long), and focuses only on the first Parent Trigger cases in California. At times it feels like a promotional video for Parent Revolution, the not-for-profit group that helps parents organize themselves and gather enough signatures to start the Parent Trigger process in motion. Some room is given to voices on the opposite side of the fence, but not enough. It is not a full picture. And teachers aren’t represented at all in the film.

I come from a family filled with teachers, so perhaps the absence of teachers in the film is something that bothered me more than it should. Teachers are on the front lines every day, dealing with unimaginable stresses on the back end, not to mention low salaries and constant criticism from every direction. It would have been nice to hear how the teachers in Compton felt about what was happening in their school district.

It would be difficult to debate that we don’t need educational reform in this country. And for parents like the ones we meet in “We the Parents”, who live in notoriously terrible school districts, there isn’t time to wait. Bureaucracy is slow and frustrating, and institutions are resistant to change. Meanwhile, as the statistics tell us in the film, in white letters on a black screen, “less than 4% of kids in Compton qualify to apply to California state university.” It is clearly an urgent situation.

Parent Revolution acts as the real “trigger” here, picking out schools to help, and, as Ben Austin, director of Parent Revolution, says, to help “incentivize a revolt” in the parents. (Austin has business-speak down cold.) Some of the parents in Compton are open to the organizers who come knocking on their door to talk about charter schools and petitions, and others say “No, thanks.” But over the course of a couple of months, enough signatures are gathered to present to the Superintendent. The petition then goes into the bureaucratic maze of School Boards and committees. The Parent Trigger Law is new, and nobody seems to know what the process really is. The people in Compton are the pioneers.

Dr. Carl Cohn, a former superintendent, gives terrific background on Compton as a community, context that is necessary to understand the bitterness that is stirred up in the community as a result of the petition. Compton, as he says, “feel(s) like they’ve been picked on by the media for years.” The people who live there are sensitive to the image of their town as overrun by violence, drive-by shootings, and chaos.

So to have it touted in the media that their schools are the worst in the state, that there is a “problem in Compton” does not go over well. School Board meetings get hostile. Parent Revolution is pilloried in the local press and local radio. One guy calls into a radio show and yells that Parent Revolution pretends it’s a grass-roots organization when really it is “funded by billionaires”! Parent Revolution does not hide its funding sources, but one can certainly understand the resentment of Compton at being overrun by do-gooders, who all wear identical T-shirts saying “I Am the Revolution.”

Marty Hillerman, of the CA Federation of Teachers, is one of the few critical voices given space in the film. He says that this “movement” belittles teachers, and it is a mistake to assume that parents know better than people who have worked in education for decades. He criticizes Parent Revolution as a “vehicle for some very rich people to found an organization and go into communities and disrupt them.”

Emotions run high. The parents interviewed are sweet, sincere, and seem bowled over by the fact that they would have any power to enact change. Many of them are high school dropouts and want better for their kids. They can’t move to a better school district. They want change locally. The pressure is on, because people like Matt Lauer and Brian Williams pontificate about what is happening on national news shows.

Cinematographer Milton Santiago shoots the streets of Compton in an emotional and simple way. There are myth-busting shots of nice houses with little lawns, girls doing cartwheels in the grass, people riding bikes. But there are also shots showing the economic devastation of the area: posters hollering “I BUY SHORT SALES,” furniture piled on the sidewalk, giant handwritten banners saying “Put Compton Back 2 Work.” Local churches often pick up the slack, providing space for people to meet and organize, as well as opening charter schools of their own.

The petition put forth by the Compton parents is rejected, on what appears to be a technicality (the petitions had no dates on them). It is a disappointment. But other communities have followed Compton’s lead. Parent Revolution is there, providing organizational help, buses to drive the parents to Sacramento to go to meetings at the State House, and, of course, lots and lots of T-shirts.

Little black-and-white cartoons give us funny visuals of how the Parent Trigger Law works, with petitions piling up on one side of a see-saw with a cute little school house on the other side. A stilted informational voiceover is used intermittently. While it is impossible to not sympathize with the parents in Compton and the other failing school districts, Marty Hillerman’s words create a giant reverb in the film, one that is difficult to ignore.

Karen Frison, the superintendent who received the Compton petition in the scene starting off the film, says later on that the entire process has helped the school board in the district to “re-think how we operate.” That is a good thing. Bureaucracies can always try for a little bit more self-awareness. But when a parent stands up at a school board meeting and says, “We just want what is best for our kids,” it makes me think of A.O. Scott’s words in his review for “Won't Back Down” (2012), based loosely on the Parent Trigger events in California: “A movie that insists, repeatedly and at high volume, that ‘it’s all about the kids’ might just cause you to wonder what else it is about, and this one is not shy about showing its ideological hand. Who, after all, could possibly be against kids?”

Three new schools will open in different communities this month in California, as a result of the Parent Trigger Law, so time will tell if it will make a difference in students’ test scores and achievement levels.

“We the Parents,” one-sided and promotional as it often feels, presents a possible solution, as well as the difficulties in achieving it.