Shakespeare’s “Twelfth Night” bears something of the same relationship to his serious romances (like “Romeo and Juliet”) that, if you will forgive the comparison, “Airplane!” bears to “Airport.” Adjust for period, genre and style, and acknowledge the fact that Shakespeare occupies a different creative universe than, say, David Zucker, and the intention is the same: Elements that are heartbreaking when handled seriously become funny when they’re pushed over the top.

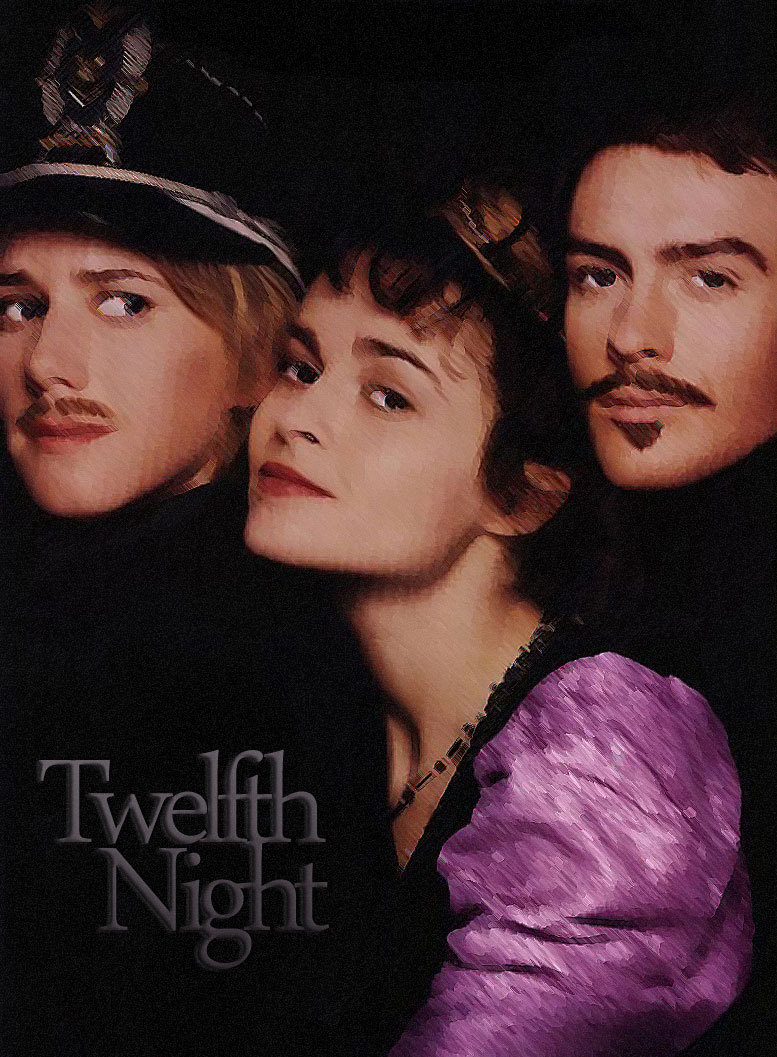

Trevor Nunn‘s new film version of “Twelfth Night,” a lighthearted comedy of romance and gender confusion, creates a romantic triangle out of the same sorts of mistaken sexual identities that inspired “Some Like It Hot.” And Nunn directs it in something of the same spirit; the film winks at us while the characters fall in love. To be sure, Imogen Stubbs makes a better boy than Jack Lemmon made a girl, but nobody’s perfect.

The period has been moved up to the 18th century, and the dialogue has been slightly simplified and clarified, but Shakespeare’s language is largely intact (and easier to understand than in Baz Luhrmann’s new “Romeo & Juliet”). Also intact is the elaborate low-comedy subplot involving the servants, which gets too much screen time relative to the main story, but supplies showcases for a ribald cast of character actors.

The story: A great storm at sea capsizes a ship. A young woman named Viola (Imogen Stubbs) is washed ashore, but believes her twin brother Sebastian has drowned. Finding herself in the unfamiliar kingdom of Ilyria, where a young woman might be at hazard, she dresses in her brother’s uniform, cuts her hair, pastes on a false mustache, and poses as a young man named Cesario.

Soon she wins a position at the court of young Count Orsino (Toby Stephens), who is desperately in love with the Lady Olivia (Helena Bonham Carter). The count sends his new page to stand before Olivia’s gate and press his case. But there are complications: Viola falls in love with Orsino, and Olivia falls in love with Viola. Since Viola cannot tell either one she is really a woman, almost every situation involving her is rich with double meaning.

“Twelfth Night” has been directed by Trevor Nunn, for 20 years a stalwart of the Royal Shakespeare Company. He knows the material, and knows the right actors to play it. Shakespeare’s language is not hard to understand when spoken by actors who are comfortable with the rhythm and know the meaning. It can be impenetrable when declaimed by unseasoned actors with more energy than experience (as the screaming gang members in “Romeo & Juliet” demonstrate).

Nunn’s casting choices make for real chemistry between Imogen Stubbs and Helena Bonham Carter (whose film debut was in Nunn’s “Lady Jane” in 1986). Bonham Carter, who has grown wonderfully as an actress, walks the thin line between love and comedy as she sighs for the fair youth who has come on behalf of the count. She wisely plays the role sincerely, leaving the winks to the other characters.

Shakespeare’s comedies all offered two levels, high and low, and here the bawdy is handled by Mel Smith as Olivia’s kinsman Sir Toby Belch, Richard E. Grant as his foppish and absurd friend Sir Andrew Aguecheek, and Ben Kingsley as the troubadour Feste. But the downstairs action is stolen by Nigel Hawthorne (“The Madness Of King George”) as Malvolio, Olivia’s chief of staff, who convinces himself Olivia loves him. Swollen with his self-importance, proud that he is impervious to the failings of mortals, he falls hard, and Shakespeare is just barely able to save his heart from breaking.

Nunn sets up all of these tensions and misunderstandings in an enchanting, beguiling style, and then lobs in a grenade with the unexpected arrival of the twin brother, Sebastian. The last scenes are exercises in double takes and sly timing. All’s well that ends well, of course, but the full title of the play provides a better key: “Twelfth Night, or, What You Will.” Since the notion of romantic love is what all of the characters are really in love with, it matters not so much who they love as that they love, allowing for the quick adjustments of focus at the end.

The movie’s key player is Imogen Stubbs, who was Emma Thompson’s rival in the 1995 “Sense And Sensibility” (she was the character Hugh Grant was engaged to, against his druthers). Here she has just that reserve that makes her character’s ridiculous situation work. She must contain her feelings about both Orsino and Olivia, even in such touchy situations as when scrubbing her employer’s back in the bath. It calls for perfect tact, which she was born with, along with a twinkle in her eye.