So bloodthirsty is Shakespeare’s “Titus Andronicus” that critics such as Harold Bloom believe it must be a parody–perhaps Shakespeare’s attempt to settle the hash of Christopher Marlowe, whose plays were soaked in violence. Other readers, like the sainted Mark Van Doren, dismiss it out of hand. Inhuman and unfeeling, he called it, and “no tragedy at all if pity and terror are essential to the tragic experience.” Certainly all agree it is the least of Shakespeare’s tragedies, as well as the first.

But consider young Shakespeare near the beginning of his career, trying to upstage the star dramatists and attract attention to himself. Imagine him sitting down to write the equivalent of today’s horror films. Just as Kevin Williamson’s screenplays for “Scream” and “I Know What You Did Last Summer” use special effects and wild coincidence to mow down their casts, so does “Titus Andronicus” heap up the gore and then wink to show the playwright is in on the joke.

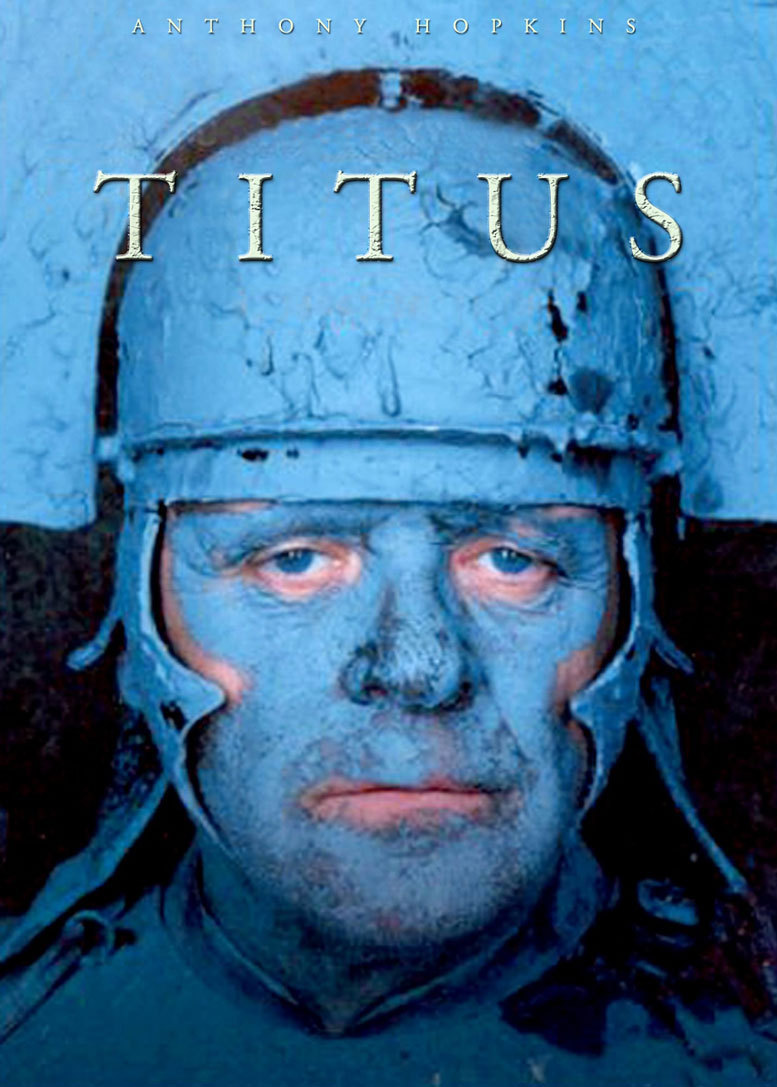

“Titus” as “Scream 1593”? Bloom cites the scene where Titus is promised the return of his sons if he will send Saturninus his hand–only to find the hand returned with only the heads of his sons. Grief-stricken, Titus assigns tasks. He, with his remaining hand, will carry one of the heads. He asks his brother to take the other. That leaves the severed hand. At this point in the play, his daughter Lavinia has no hands (or tongue) after being raped and mutilated by Queen Tamora’s sons, and so he instructs her, “Bear thou my hand, sweet wench, between thy teeth.” Bloom invites scholars to read that line aloud without smiling, and says Shakespeare knew the play “was a howler, and expected the more discerning to wallow in it self-consciously.” That is exactly what Julie Taymor has done, in a brilliant and absurd film of “Titus Andronicus” that goes over the top, doubles back and goes over the top again. The film is imperfect, but how can you make a perfect film of a play that flaunts its flaws so joyfully? Some critics have sniffed at its excesses and visual inventions–many of them the same dour enforcers who didn’t like the biblical surprise in “Magnolia.” I have had enough good taste and restraint for a lifetime, and love it when a director has the courage to go for broke. God forbid we should ever get a devout and tasteful production of “Titus Andronicus.” It cannot be a coincidence that the title role is played by Anthony Hopkins. Not when by Act 5 he is serving Tamora (Jessica Lange) meat pies made out of her sons and smacking his lips in precisely the same way that Hannibal Lecter drooled over fava beans. “Titus Andronicus” was no doubt Lecter’s favorite Shakespeare play, opening as it does with Titus returning to Rome with the corpses of 21 of his sons and their four surviving brothers, and pausing in his victory speech only long enough to condemn the eldest son of Tamora, vanquished queen of the Goths, to be hacked limb from limb, and the pieces thrown on a fire.

Titus is not the hero of the film because it has no hero. He is as vicious as the others, and when he notes that “Rome is a wilderness of tigers,” he should have included himself. Hopkins plays him, like Hannibal Lecter, as a man pitiable, intelligent and depraved, as he strides through a revenge story so gory that there seems a good chance no one will be left alive at the end.

Some of the contrivance is outrageous. Consider the scene where a hole in the forest floor gradually fills up with corpses, as Aaron the Moor (Harry Lennix), the play’s grand schemer, unfolds a devious plot to defeat both Titus and Saturninus and seduce Tamora. This hole, of course, would be convenient on the stage, where it could be represented by a trapdoor. But in the woods, as Saturninus (Alan Cumming) apprehensively peers over the side, it takes on all the credibility of an Abbott and Costello set-up. Or consider the scene late in the play where Titus breaks the neck of his own long-suffering daughter, as if losing her tongue and arms were not bad luck enough, and then pities the fates that made him do it.

Taymor is the director of the Broadway musical “The Lion King,” which is one of the most exhilarating experiences I have ever had in a theater. In her first film, she again shows a command of costumes and staging, ritual and procession, archetypes and comic relief. She makes it clear in her opening shot (a modern boy waging a food fight with his plastic action figures) that she sees the connection between “Titus Andronicus” and the modern culture of violence in children’s entertainment. “Titus” would make a video game, with the tattooed Tamora as Lara Croft.

Taymor’s period is basically a fanciful version of ancient Rome, but in the mix she includes modern cars and tanks, loudspeakers and Popemobiles, newspapers and radio speeches. Like Richard Loncraine and Ian McKellen’s “Richard III” (1996), she sees the possibilities in fascist trappings as Saturninus seizes control of Rome and marries Tamora. There’s a jazzy wedding orgy, crypto-Nazi costuming and a scene staged in front of a vast modern structure made of arches, a reminder of the joke that fascist architecture looked like Mussolini ordered it over the phone.

Taymor lavishes great energy on staging and photography. Like the makers of a cartoon, she and her cinematographer, Luciano Tovoli, sometimes move the camera in time with music or sound effects; as the picture swoops or pulls away, so does Elliot Goldenthal’s score. There are scenes of rigid choreography, as in the entry into Rome, where Titus’ army marches like the little green soldiers in “Toy Story.” And other scenes where the movements are so voluptuous, we are reminded of “Fellini Satyricon.” Mark Van Doren was correct. There is no lesson to be learned from “Titus Andronicus.” It is a tragedy without a hero, without values, without a point, and therefore as modern as a horror exploitation film or a video game. It is not a catharsis, but a killing gallery where the characters speak in poetry. Freed of pious meaning, the actors bury themselves in technique and the opportunity of stylized melodrama. Anyone who doesn’t enjoy this film for what it is must explain: How could it be more? This is the film Shakespeare’s play deserves, and perhaps even a little more.