Was ever there a villain such as Richard the Third? Murderer of his brother Henry VI; of Prince Edward; later of Edward’s wife Anne; of his own brother Clarence; of Anne’s brother Rivers; of his henchmen Grey and Vaughn; of Lord Hastings; his own two young nephews; of Lady Anne; and finally his long-loyal retainer Buckingham. All had to make way for Richard’s overwhelming ambition to rise to the throne. All died in vain, as Richard was unmounted in battle and uttered the famous cry: “A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse!”

Or so Shakespeare has it, and his Richard III is the version that has been popularly accepted for centuries. English history tells a different story, depriving Richard even of his most famous crime, the execution of his two nephews. Richard, in fact, may not have been entirely evil at all, but as John Ford has a character say many years later, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” Certainly Richard III is one of the most memorable characters in all of Shakespeare.

His Richard is vile and without merit, universally loathed, loathing himself. A hunchback, he looks in the mirror on the play’s first scene and described what he sees: Deformed, unfinished, sent before my time into this breathing world, scarce half made up, and that so lamely and unfashionable that dogs bark at me as I halt by them. The historical Richard was of perfectly average proportions, but Shakespeare’s invention has given countless actors an embellishment to be grateful for.

Harold Bloom argues in his book Shakespeare: The invention of the Human that the bard all but invented human character in drama and fiction by creating characters who were self-aware, and shared their feelings with the audience. In the same opening scene, Richard, who is pathologically secretive, openly shares his plans with us: …therefore, since I cannot prove a lover…I am determined to prove a villain. Throughout the play he casts an eye at the audience and reveals his inner thoughts.

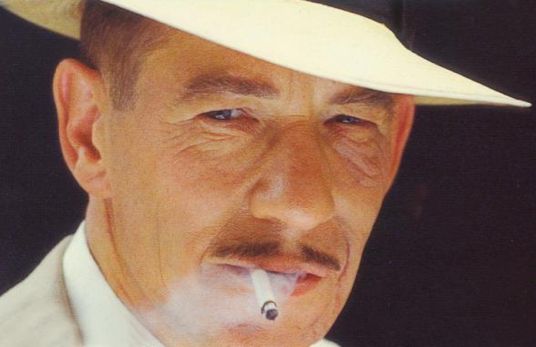

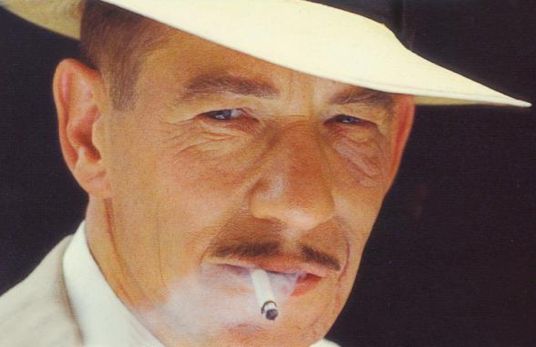

Bloom thought Sir Ian McKellen was the greatest Richard III he had ever seen, and Richard Loncraine’s 1995 film is based on McKellen’s famous 1990 National Theater performance . It sets the play in an England of an alternate timeline, which clearly evokes 1930s fascism. In recent London, Shakespeare’s language remains the same; I imagine the playwright himself would have cared little about the sets and costumes of a staging so long as his words were respected.

This is a film with a dread fascination. McKellen occupies it like a poisonous spider in its nest. Lurching sideways through his life, smoking as if it’s as necessary to him as breathing, seductive when he wants to be, when angered Richard reveals the predator within. As he makes a great show of loving his little nephews, one of them jumps playfully on his deformity and he snarls and bares his teeth like a jackal. When a retainer gives him an apple to feed to a pig, he throws it at the animal, nodding with quiet satisfaction at its squeal.

Yet this Richard has a reptilian charm. One of the most audacious proposals in all of literature occurs when Richard, who in the play has caused the death of Henry VI and his son Edward, follows Edward’s’ widow Anne (Kristin Scott Thomas), as she accompanies the corpse of her husband through the streets. He confides in us: He plans to marry her, and congratulates himself on his boldness:

Was ever woman in this humour woo’d? Was ever woman in this humour won? I’ll have her; but I will not keep her long. What! I, that kill’d her husband and his father, To take her in her heart’s extremest hate, With curses in her mouth, tears in her eyes…

Years in fact passed between the murder and their wedding, but never mind; notice a small touch added by Loncraine and McKellen. After softening her up, Richard offers her a ring, which she accepts. All very well. But he removes the ring from his own finger by sticking it in his mouth and lubricating it with saliva, so that as he slips it on her finger she cannot help but feel the spit of her husband’s murderer.

Such extra measures of repulsive detail scuttle through the entire film, making this “Richard III” perversely entertaining. When I saw it with a large audience, it chuckled almost the way people did during “Silence of the Lambs;” Richard, like Hannibal Lector, is not only a reprehensible man, but a smart one, who is in on the joke. He relishes being a villain; it is his revenge on the world.

From the start the film gives us the sense of being privileged insiders, knowing Richard better than any of the characters. The famous opening lines (“Now is the winter of our discontent”), begin in public glory, and then conclude in private, standing at a urinal, speaking directly to the camera.

This Richard has an uncanny power to control men. His close aides and confidants know full well the enormity of his crimes and the innocence of his victims. Yet smoothly, without question, they nod at his commands and cry them out. The chief of the admirers is Lord Buckingham (Jim Broadbent), his hair slicked back, his face always in judicious neutrality, quick to smile and agree. We are reminded of the works of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar:

Let me have men about me that are fat; Sleek-headed men and such as sleep o’ nights

He, too, will eventually fall to Richard’s paranoia, so that at the end, fallen in battle, Richard is alone, all alone. He goes to bed uneasy:

I have not that alacrity of spirit, Nor cheer of mind, that I was wont to have.

Then follows the dreadful nightmare during which he is visited by the accusing ghosts of all his victims. Her awakes trembling:

It is now dead midnight. Cold fearful drops stand on my trembling flesh. What do I fear? myself? there’s none else by: Richard loves Richard; that is, I am I. Is there a murderer here? No. Yes, I am: Then fly. What, from myself?

Yes, from himself, the final evil he cannot flee.

Richard III,written in about 1591, is said to be Shakespeare’s first great play. We can only speculate about the effect it had on its first audiences. The Elizabethan drama was a great popular art form, created not for royal courts but for poor groundlings who paid a penny to stand in the pit beneath the stage, or bourgeois such as Pepys, who paid a little more to be sure of a seat and a good view.

What Shakespeare and his contemporaries were creating was, if you will, an early form of the gutter press, in which the misdeeds of the great were presented for the entertainment of the commoners. Yet they were written in sublime verse and contained profundities we are still awed by; at the dawn of the English language, that was an age of genius , and at its summit stood Shakespeare, the most extraordinary artist in any medium in human history.

McKellen has a deep sympathy for the playwright. In London I saw his one-man show “Acting Shakespeare,” in which he effortlessly commands many of Shakespeare’s great characters, evoking period, setting and character with only his gift and some lighting. On the stage McKellen has also played Hamlet, King John, Lear, Romeo, Macbeth, Coriolanus and Othello. Here he brings to Shakespeare’s most tortured villain a malevolence we are moved to pity. No man should be so evil, and know it. Hitler and others were more evil, but denied out to themselves. There is no escape for Richard. He is one of the first self-aware characters in the theater, and for that distinction he must pay the price.