“The Lost City of Z” is about an Englishman who’s determined to find an ancient city in the Brazilian jungle. But it’s really about what happens when you get older and realize that your youthful dreams haven’t come true yet: you either ratchet expectations back a bit, or double down and charge harder in the direction of your obsession, realizing that it’s not as easy to maintain momentum as it used to be. Viewers who are familiar with the true story the film is based on will enjoy it on an immersive level, savoring the period details and arguing about whether they were represented accurately by writer and director James Gray (“We Own the Night,” “The Immigrant“). as well as whether the film is anti-colonial enough for modern tastes. Those who don’t know anything about the tale going in (a category that included me) might be gobsmacked by what happens. The order of events doesn’t stick to any established commercial movie template. What happens feels as random yet inevitable as life itself.

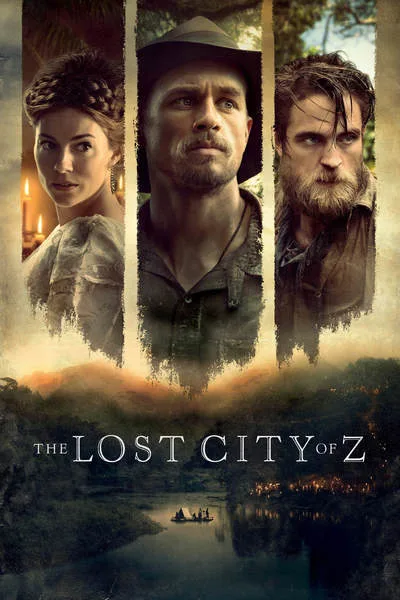

Charlie Hunnam stars as Percy Fawcett, a British Army officer who in the first part of the 20th century led expeditions into the Amazon jungle to find the titular city, which he named Zed, or Z. Fawcett hoped that finding Z would prove his theory that—contrary to the racist attitudes of the same people funding his expeditions—certain nonwhite civilizations were more advanced than any western society in existence at the same time. Percy also had deeper, personal motivations, chief among them to prove himself a respectable Englishman, especially since his father’s Army career destructed in a blaze of alcoholic misbehavior (“He’s been rather unfortunate in his choice of ancestors,” a superior officer says of Percy). Percy would never describe himself in these terms, because Freudian self-analysis wasn’t a thing back then, but he is driven by a need to prove that he’s the opposite of his father in every way: a reliable officer, an important explorer, a dedicated family man.

That last ambition takes a bit of a hit, though, because Percy keeps going back to the jungle in hopes of finding the lost city. His wife Nina (Sienna Miller) is a proto-feminist, or at least more liberated than English army wives tended to be in the early 1900s. When she speaks of their marriage as a partnership of equals, it’s clear that she really means it, and that Percy and the movie respect her vision. But as Nina points out, when Percy repeatedly leaves England for South America to lead a band of similarly obsessive men (including his best friend, Corporal Henry Costin, a terrific character turn by Robert Pattinson) he’s forcing her into the traditional role of supportive wife and caretaker to their kids, and assuming that she’ll subordinate her own dreams (which he hasn’t asked about) to his.

Gray has become one of my favorite American filmmakers. He has the ability to do what’s called “world building” in science fiction and fantasy, but with real subcultures and places. Whether he’s imagining 1990s outer-borough New York City in “Little Odessa” and “The Yards” or the turn-of-the-century Lower East Side in “The Immigrant,” he and his production team are phenomenally attentive to fine details of grooming, dress, posture, and speech. They even notice the different ways that light falls on faces and the folds of clothing depending on whether a scene is lit by fluorescent lights, early oil lamps, a campfire or the moon. Here, as in his other films, you never feel that you’re watching one of those prototypical Oscar-baiting period movies where “every dollar is onscreen” but everything feels a bit too polished and carefully arranged. Whether it is re-creating a fancy dress ball filled with English Army officers and their partners and servants or a camp in the Amazon basin staffed with slaves and ruled by the Portuguese boss of a rubber trading company (a brief but sensationally effective appearance by Franco Nero), “The Lost City of Z” doesn’t unveil a world but merely presents it, in a matter of fact way, by having characters exist within it.

More important, though, is the film’s attention to character. Visually, Percy’s story is aligned with a tradition of films about white Europeans traveling to “exotic” parts of the world and getting swallowed up by their obsessions. There are unabashed nods to “Lawrence of Arabia,” “Apocalypse Now” and several Werner Herzog classics; you even get a double-hit of “Apocalypse Now” and “Fitzcarraldo” when Percy and his explorers come upon an opera house that was built to bring high European culture to the “savages.” The ironies, indignities and cruelties of this era are never far from the film’s mind.

There’s a long, unexpectedly gripping scene deep in the movie where Percy tries to justify the need for another expedition to a roomful of peers who think of South America as a land of exploitable subhumans that’s of interest only for its natural resources. The film doesn’t sugarcoat their casual viciousness and greed, but it doesn’t turn Percy into a white savoir, either. Here, as elsewhere, Percy is only slightly more sensitive than the people whose money and approval he seeks. He treats the Amazon tribespeople with respect and affection, but they are ultimately a means to an end, a way of getting him closer to his dream of finding that city.

Percy’s behavior toward his family is equally complicated, admirable in some ways and appalling in others. He’s a kind and decent individual, and he seems genuinely sorry for all the grief he puts his wife through, and guilty for letting his children grow up while he spends years away from them. But he still keeps going back into the jungle, and he eventually draws his eldest son Jack (played as a teenager by Tom Holland) into his dream, while seeming oblivious to the fact that he’s exploiting the boy’s desire to get close to a dad who was never around.

The movie has its problems. There are moments when Nina’s dialogue strains to convince 21st century viewers that the character is fiery and independent. Percy can be too recessive and nice for the film’s own good. And a depiction of trench combat in World War I Europe, which interrupted Percy’s trips to South America, is appropriately harrowing but did not need to take up as much real estate as it does. (The war sequence also contrives to place previously established characters together on the same battlefield for the sake of narrative continuity when they probably weren’t all there in life—a rare case where the movie seems to be coddling the viewer.)

But Hunnam’s performance is charming and lived in, easily the best work he’s ever done, and scene for scene, this is a splendid film. As shot by Darius Khondji (“Seven“), who’s better at re-creating early man-made light sources than any living cinematographer, the movie is beautiful but never ostentatiously pretty. And it’s wise about how to use actual historical events as metaphors for basic desires (to succeed, to redeem oneself). It never forgets that that these were real people whose words and deeds had consequences that should not be swept under the carpet for the sake of a happy ending.