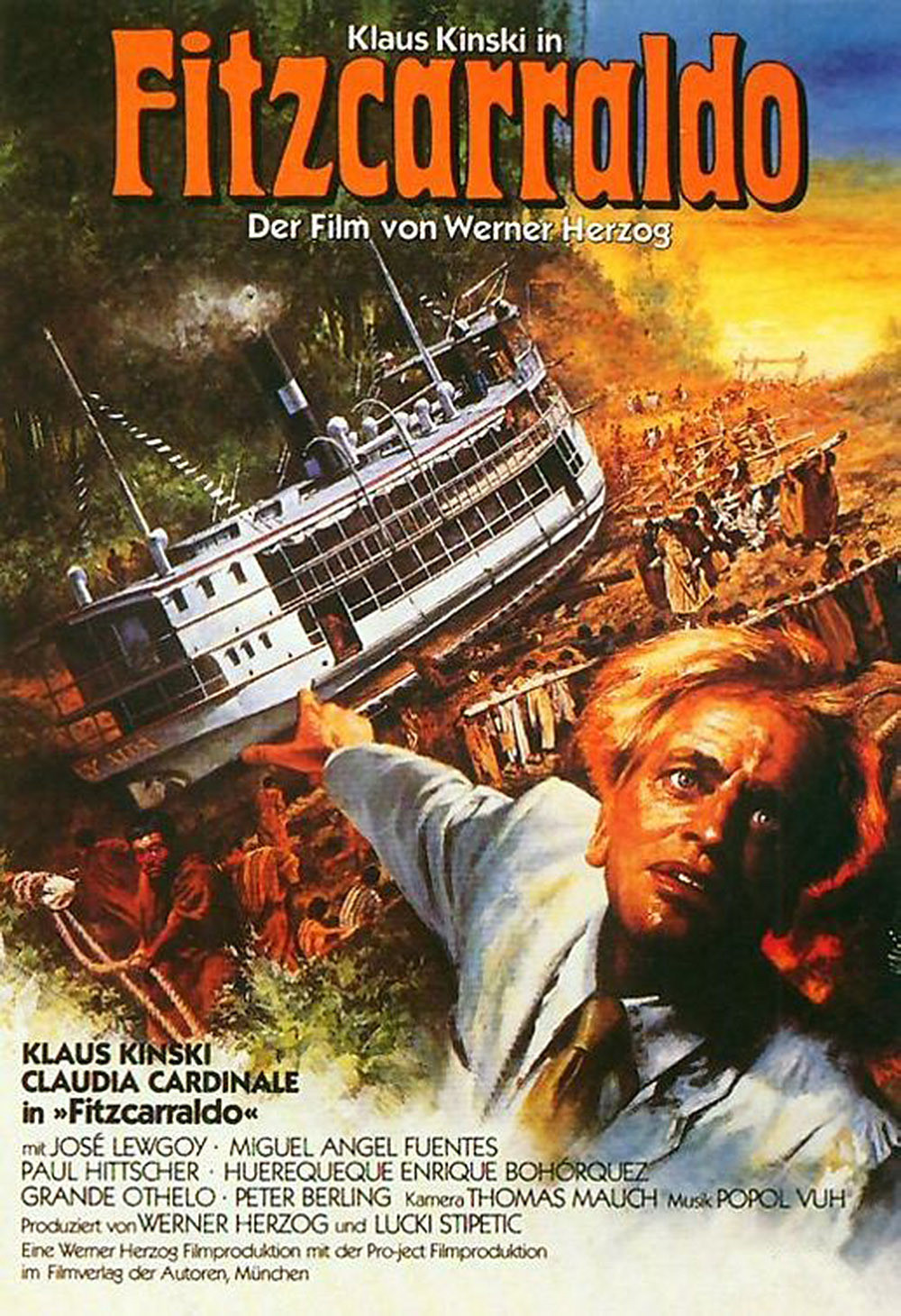

Werner Herzog‘s “Fitzcarraldo” is one of the great visions of the cinema, and one of the great follies. One would not have been possible without the other. This is a movie about an opera-loving madman who is determined to drag a boat overland from one river system to another. In making the film, Herzog was determined to actually do that, which is more than can be said for Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, the Irishman whose story inspired him.

“Fitzcarraldo” (1982) is one of those brave and epic films, like “Apocalypse Now” or “2001,” where we are always aware both of the film, and of the making of the film. Herzog could have used special effects for his scenes of the 360-ton boat being hauled up a muddy 40-degree slope in the jungle, but he believed we could tell the difference: “This is not a plastic boat.” Watching the film, watching Fitzcarraldo (Klaus Kinski) raving in the jungle in his white suit and floppy panama hat, watching Indians operating a block-and-tackle system to drag the boat out of the muck, we’re struck by the fact that this is actually happening, that this huge boat is inching its way onto land — as Fitzcarraldo (who got his name because the locals could not pronounce “Fitzgerald”) serenades the jungle with his scratchy old Caruso recordings.

The story of the making of “Fitzcarraldo” is told in “Burden of Dreams” (1982), a documentary by Les Blank and Maureen Gosling, who spent time in the jungle with Herzog, his mutinous crew and his eccentric star. After you see the Herzog film and “Burden,” it’s clear that everyone associated with the film was marked, or scarred, by the experience; there is an impassioned speech in “Burden” where Herzog denounces the jungle as “vile and base,” and says, “It’s a land which God, if he exists, has created in anger.”

“Fitzcarraldo” opens on the note of madness, which it will sustain. Out of the dark void of the Amazon comes a boat, its motor dead, the shock-haired Kinski furiously rowing at the prow, while his mistress (Claudia Cardinale) watches anxiously behind him. They are late for the opera. He has made some money with an ice-making machine, she is a madam whose bordello services wealthy rubber traders, and as they talk their way into an opera house, Fitzcarraldo knows his mission in life: He will become rich, build an opera house in the jungle, and hire Caruso to sing in it.

Fortunes in this district are built on rubber. He obtains the rights to 400 square miles that are thought to be useless because a deadly rapids prevents a boat from reaching them. But if he could bring a boat from another river, his dream could come true. The real Fitzgerald only moved a 32-ton boat between rivers, and he disassembled it first. Hearing the story, Herzog was struck by the image of a boat moving up a hillside, and the rest of the screenplay followed.

His production can be described as a series of emergencies. A border war between Peru and Ecuador prevented him from using his first location. He found another location and shot for four months with Jason Robards playing Fitzcarraldo and Mick Jagger playing his loony sidekick. Then Robards contracted amoebic dysentery and flew home, forbidden by his doctors to return, and Jagger dropped out. Herzog turned to Klaus Kinski, the legendary wild man who had starred in his “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” (1972) and “Nosferatu” (1979). Kinski was a better choice for the role than Robards, for the same reason a real boat was better than a model: Robards would have been playing a madman, but to see Kinski is to be convinced of his ruling angers and demons.

Herzog has always been more fascinated by image than story, and here he sears his images into the film. He worked with indigenous Amazonian Indians, whose faces become one of the important elements of the work. An early scene shows Fitzcarraldo awakened from sleep to find his bed surrounded by children. There is a scene where Indians gaze impassively at the river, not even noticing Fitzcarraldo as he ranges up and down their line, peering wildly into their faces. There is another scene where he and his boat crew eat dinner while Indians crowd into the mess room and stare at them. And scenes simply of faces, watchful, judgmental, trying to divine what drives the man in the white suit.

Herzog admitted that he could have filmed his entire production a day or two outside Quito, the capital of Ecuador. Instead, he filmed in the rain forest, 500 miles from the nearest sizable city. That allows shots like the one where Fitzcarraldo and his boat captain stand in a platform at the top of the tallest tree, surveying the vastness around them. He has spoken of the “voodoo of location,” which caused him to shoot part of his “Nosferatu” in the same places where Murnau filmed his 1926 silent version. He felt the jungle location would “bring out special qualities in the actors and even the crew.” This was more true than he could have suspected, and in the fourth year of his struggle to make the film, exhausted, he said, “I am running out of fantasy. I don’t know what else can happen now. Even if I get that boat over the mountain, nobody on this earth will convince me to be happy about that, not until the end of my days.”

“Burden of Dreams” tells of arrows shot from the forest, of the boat slipping back down the hill, of the Brazilian engineer resigning and walking away after telling Herzog there was a 70 percent chance that the cables would snap and dozens of lives would be lost. On a commentary track, we learn more horrifying details; a crew member, bitten by a deadly snake, saved his own life by instantly cutting off his foot with the chain saw he was holding. In an outtake from “Burden,” which Herzog used in “My Best Fiend” (1999), his documentary about his stormy relationship with Kinski, we see the actor raging crazily on the set. “Burden” has an image that will do for the entire production: Herzog wading through mud up to his knees, pulling free each leg to take another step.

The movie is imperfect, but transcendent; this story could not have been filmed on this location in this way and been perfect without being less of a film. The conclusion, the scene with the cigar, for example, is an anticlimax; but then everything must be an anticlimax after the boat goes up the hill. What is crucial is that Herzog does not hurry his story along; he seeks not the progress of the plot, but the resonance of the images. Consider a sequence where the boat actually bangs and crashes its way through the deadly Pongo das Mortes, the Rapids of Death. Another director might have made this a routine action scene, with quick cuts and lots of noise; Herzog makes it a slow and frightful procession down real currents in a real ship, with a phonograph playing Caruso until he needle is knocked loose. It looks more horrifying to see the huge ship slowly floating to its destiny.

Among directors of the last four decades, has anyone created a more impassioned and adventurous career than Werner Herzog? Most people have only seen a few of his films, or none; he cannot be fully appreciated without a familiarity with his many documentaries and more obscure features (such as “Heart of Glass” and “Stroszek“). His 2005 documentary “Grizzly Man,” about a man who spent 13 summers with the grizzly bears of Alaska, is the spiritual brother of “Fitzcarraldo” — both times, men are driven by obsession to challenge the wilderness. Again and again, in films shot in Africa, Australia, Southeast Asia and South America, he has been drawn to the farthest reaches of the earth and to the people who live there with their images uncorrupted by the thin gruel of mass media.

“I don’t want to live in a world without lions, and without people who are lions,” he says in “Burden of Dreams.” At the darkest hour in “Fitzcarraldo,” when Robards fell sick and he had to abandon four months of shooting, Herzog returned to get more backing from investors. They had heard he was finding it impossible to get the ship up the mountain, and asked if it would not be wiser to take his losses and quit. His reply: “How can you ask this question? If I abandon this project, I will be a man without dreams, and I don’t want to live like that. I live my life or I end my life with this project.” With Herzog, that has often been the case.

“Fitzcarraldo” is on DVD, and “Burden of Dreams” is new in the Criterion Collection.

See also: A Q&A with Herzog, Ebert’s 1982 review of “Fitzcarraldo” and Great Movies reviews of “Aguirre, the Wrath of God,” “Stroszek” and Murnau’s “Nosferatu.”