At the heart of “Sophie Scholl: The Final Days” is a long interrogation conducted across a desk in a police headquarters. It is February 1943, in Munich. The questions are asked by Robert Mohr (Alexander Held), a provincial who has risen in rank under the Nazis and wears a little lapel pin proclaiming his patriotism. The answers come from Sophie Scholl (Julia Jentsch), a student of biology and philosophy. She is accused of helping to distribute leaflets on her campus that attack Hitler and his war.

This is not a thriller but a police procedural, in which we have all the information we need, right from the outset. She is guilty. Sophie and her brother Hans (Fabian Hinrichs) belong to the White Rose, an underground group that mimeographs statements critical of the regime and the continuation of a war that is already lost. In theory their leaflets were to be mailed. Hans gets the idea of distributing them on their campus. This is reckless and stupid and exactly the sort of grand gesture beloved by idealistic kids. If the Scholls had been communists, party discipline would have mocked them. But they are Catholics carried away by conscience.

Even so, they might have gotten away with it. They put piles of leaflets outside classroom doors, and then Sophie, in a heedless moment, sends a stack of paper swirling down into a central hallway. It is the janitor who turns them in, in part because he is a Nazi toady, in part because they made extra work for him.

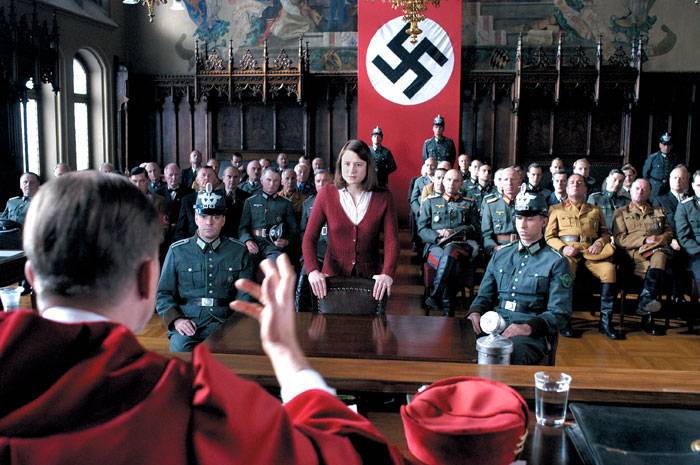

“Sophie Scholl,” an Oscar nominee for best foreign film, contains no artificial suspense or drama. Directed by Marc Rothemund and written by Fred Breinersdorfer, it is based on fact and uses the transcripts of Scholl’s actual interrogation and trial, as kept by the Gestapo and liberated when East Germany fell. Most of the words in the questioning are literally what Scholl and Mohr said. He sits behind his desk, impassive and precise, asking her to explain her presence on the campus, and her suitcase that is exactly large enough to hold the leaflets. Cool and calm, she answers every question precisely. She has an alibi that is almost good enough.

The effect of this scene is so powerful that I leaned forward like a jury member, wanting her to get away with it so I could find her innocent. But the law moves as the law always does, with no reference to higher justice; even in this Nazi procedure there are carbon copies and paper clips and rubber stamps and a need to see the law followed, as indeed it is. The law underpins evil, but it is observed. When Sophie is found guilty, it is legal enough.

The sentence against her is carried out with startling promptness; because of the movie’s title, we are not surprised, but we are jolted. I was reminded of an exchange in “Thank You for Smoking,” where the son of a tobacco lobbyist asks him, “Dad, why is the American government the best government?” And his father replies, “Because of our endless appeals system.” It is a luxury to be able to joke about such things. One day Sophie Scholl thoughtlessly throws some leaflets off a balcony, and two days later she is dead. Notice how the final sounds of the movie play under a black screen. Does she hear them?

Are the policeman Robert Mohr and the judge Roland Freisler (Andre Hennicke) evil men? Yes, absolutely, but they are doing their duty. I learn from Anthony Lane in The New Yorker that Mohr’s widow received a state pension after the war. The police and the court are shown to follow the law, and in the law resides either good or evil, depending on what the law says and how it is enforced. That is why it is crucial that a constitution guarantee rights and freedoms, and why it is dangerous for any government to ignore it. There should be no higher priority.

All of these thoughts are made particular in “Sophie Scholl: The Final Days.” Most of the dialogue involves specific questions of where Sophie was, and when, and why the evidence against her is so compelling. Perry Mason type stuff. The policeman is so passive he is hardly there. Only the judge indulges in speechifying; those who know their actions are wrong are often the loudest to defend them, especially when they fear a higher moral judgment may come down on them. But the most powerful political statement in the film is one of the saddest. Sophie is allowed a few moments with her parents before being taken away forever. “You did the right thing,” her father says of Sophie and her brother. “I’m proud of you both.”