“After I die, I’ll have plenty of time to rest. Let’s go to work.” According to the documentary “Sembene!”, the Sengalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembene said that to a friend during the production of his final, masterful feature, 2004’s “Moolaade,” which Roger Ebert called “the kind of film that can only be made by a director whose heart is in harmony with his mind.” It was a drama about a young woman who had miraculously escaped the ritual of female genital mutilation in her family, only to be threatened by it after getting engaged to a villager who had returned home after a period in France. Sembene, one of the most influential filmmakers and political figures produced by the African continent in the 20th century, was almost 80 when he directed the film, and had seen several of his serenely confrontational films banned in Senegal, France and elsewhere. He was so tired and sick that at night he would sleep hooked up to intravenous drip bags of nutrients and then wake up the next morning and continue filming, wearing his young colleagues out.

This is but one of many stories in “Sembene!” that make the director, who died in 2007, sound not just like a great artist and relentless person, but a figure out of a legend or folktale: an invincible juggernaut of a storyteller; the man who gave voice to African stories that, until the early post-colonial period, had been largely voiceless on film. It is unabashedly celebratory and mainly concerned with the work and the meaning of the work, at times coming on like an episode of the generally worshipful PBS series “American Masters” about somebody who is not American, and either ignoring or glancing over uncomfortable aspects of Sembene’s personal life. These include an account of the collapse of his marriage to Carrie Moore, a woman he once described as his “muse”; and the time he helped initiate a fund for new African filmmakers and then essentially hijacked one of the most interesting projects, the 1988 military mutiny drama “Camp de Thiaroye,” from his protege Bouboucar Boris Diop, and helped himself to a lot of the development fund to make it. (“My contradictions are trivial compared to the necessity of getting the film made,” he said soon after.)

This approach might become tiresome, or seem suspect, if “Sembene!” didn’t frame the story in terms of the necessity of bearing witness and keeping a legacy alive. It’s not making a tough, probing look at the psychology of an artist, and even the interplay of Sembene’s personal life and art is somewhat minimized compared to other filmed biographies in this vein. It’s all framed in terms of representative images, the right to be heard, and the ability to tell stories that challenge official narratives of power.

Sembene himself told the Guardian in a 2005 profile that “Moolaade” “…isn’t just entertainment: I call it ‘movie school,'” and that the point is to present Africans with images of Africans dealing with African realities, so that cinema becomes a “mirror” for them. This documentary is very much made in that spirit, although it lacks Sembene’s sly humor and his knack for poking holes in puffed-up official images, and it largely ignores much of his output as a novelist and poet (except for key works represented onscreen by animated “paintings” and stray lines of narration).

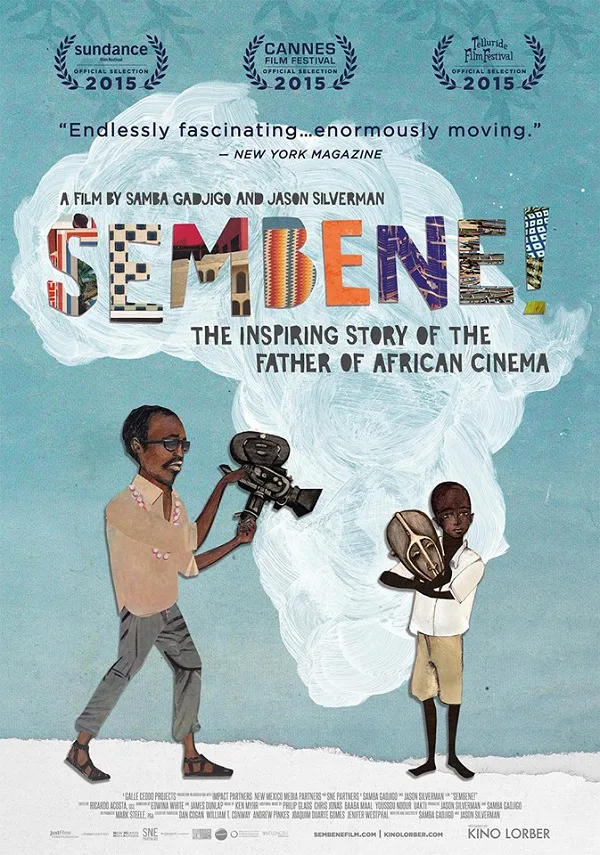

The movie is co-directed by Jason Silverman and the Senegal-born Samba Gadjigo, a Mount Holyoke professor of French and African studies and Sembene’s official biographer. It begins with Gadjigo talking about his mission to preserve Sembene’s film work and personal effects, and when we see what they look like when the process began, we’re horrified: many of the film canisters containing his personal prints and unseen footage are rusted; a few have rotted and their contents appear to have already disintegrated.

The film then takes us on a tour of some of the highlights of his life, many of which sound like milestones in a hero’s origin story. There’s the time in 1946 French-ruled Senegal when he was expelled from school for retaliating against a white schoolteacher who had slapped him by striking the man across the face. There’s the time he broke his back while unloading ships in Marseilles and redoubled his commitment to Marxism and labor rights and then wrote his first novel, the 1956 colonial exploitation allegory “Black Docker,” about an African dockworker who kills a white woman who had tried to steal the manuscript of his novel and claim she had written it. We learn about, and see footage from, his major features, including “Xala” (1975), which dared mock and expose corruption in African governments; “Ceddo” (1977), which depicted militant Muslims in Africa as another kind of culturally invading force, and “Guelwaar” (1992), about businessman who is found dead after publicly warning against the influence of foreign aid, which he believed made native governments dependent and corrupt.

The film’s emphasis on Sembene’s importance becomes too insistent and sometimes maudlin, to the point where it starts to feel like we’re watching a wake for somebody who died just last month. One wishes that the filmmakers had allocated more of the screen time spent telling us how important Sebene was to exploring Sembene’s films and prose in greater detail, because the sections that deal specifically with what Sembene’s films say and how they say them are among the best examples of populist-minded film education that you’ll see. These parts of the movie seem to have been designed to split the difference between satisfying viewers who know a bit about Sembene and African cinema and those who are coming to it for the first time. The very knowledgeable, somewhat knowledgeable and entirely uninformed should all come away feeling that the intent of key films has not just been represented accurately, but in such a way as to spur greater public curiosity, which is ultimately job one of a film like this, with its images of Semebene’s office caked with dust and his film prints corroded.

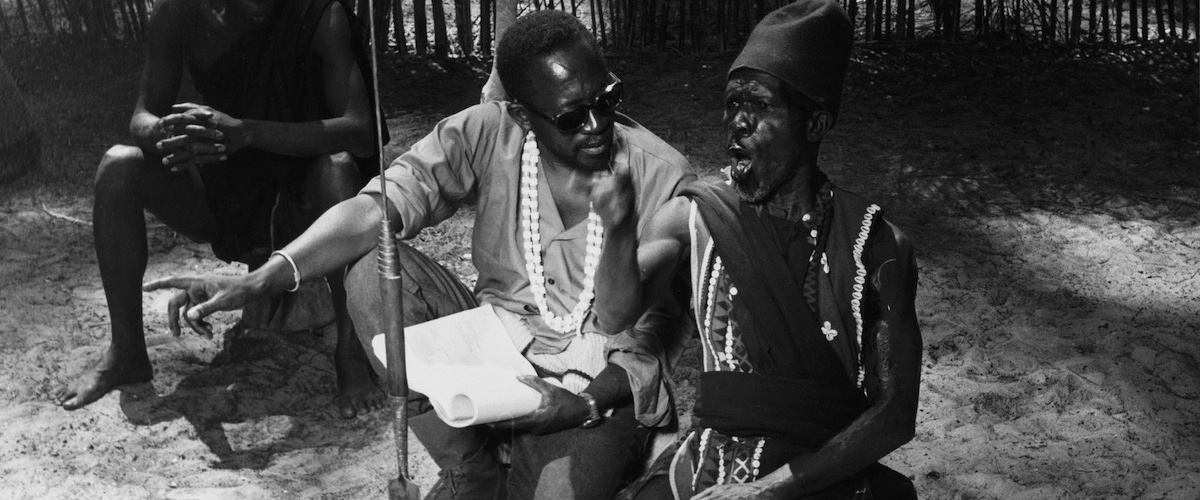

“Sembene!” is most illuminating when it is simply showing us clips from the director’s features and behind-the-scenes or “making of” footage, with very little in the way of verbal setup, and then letting them play out. One of the recurring points made by various witnesses is that until Sembene burst onto the scene, images of Africa were mainly about pretty scenery with exotic wildlife that visiting American and English movie stars could have adventures in front of. In other words, the continuation of colonialism through cinema. Sembene did much to counter that tendency, although he never enjoyed the kind of widespread acclaim that other international directors, including Chinese and Japanese masters, have sometimes enjoyed in Western nations.

The filmmakers seem especially fond of images of black characters in Sembene’s movies simply going on about their daily business, then pausing for a moment and looking this way and that way, as if wondering if anyone notices them, much less truly sees them. Sembene did, and his films asked audiences to do the same. It’s a small measure of his continued importance, as well as the world cinema’s general failure to pay attention to directors of color, that each time we see an image of Sembene with a camera in this documentary, it still feels like a revolutionary statement.