Holden Caulfield hated phonies. He detested the superficial fantasies offered by Hollywood yet still yearned for the lost innocence of his youth. As the beloved teenage protagonist of J.D. Salinger’s 1951 literary masterpiece, The Catcher in the Rye, Caulfield has always upstaged the enigmatic author who brought him to life. Danny Strong’s “Rebel in the Rye” attempts to correct that by placing Salinger at the center of his own biopic, while utilizing Kenneth Slawenski’s 2010 biography, J.D. Salinger: A Life, as its chief source material.

This sounds like a promising approach at the outset, but the execution is riddled with problems, not the least of which is the absence of Salinger’s actual work. We get fragmented excerpts of his text along with some wordless homages (such as the novel’s iconic carousel), but no real sense of his genius. Jim Jarmusch’s “Paterson” masterfully demonstrated how the essence of William Carlos Williams’ poetry could be captured cinematically, immersing us in the rhythm and tone of his text. Strong’s film is less interested in what Salinger did than in what led him to do what he did. It assumes the audience has already read Catcher in the Rye, and on that level, it’s a missed opportunity.

As a character study, the picture is efficiently made and never less than watchable, but it lacks the urgency and inspiration of Strong’s best work. His two great scripts for Jay Roach’s HBO films, 2008’s “Recount” and 2012’s “Game Change,” take place over much narrower time spans and delve into the minutia of well-documented events in political history. As revealing a profile as Slawenski’s book may have been, it still left countless facets of Salinger’s life shrouded in mystery. Just as the majority of his writing has been kept from the public eye, most of the author’s years were spent in the isolation of his New Hampshire cabin. So many details are missing from this narrative that it feels more like a series of biographical beats mixed with theories than a fully fleshed-out portrait.

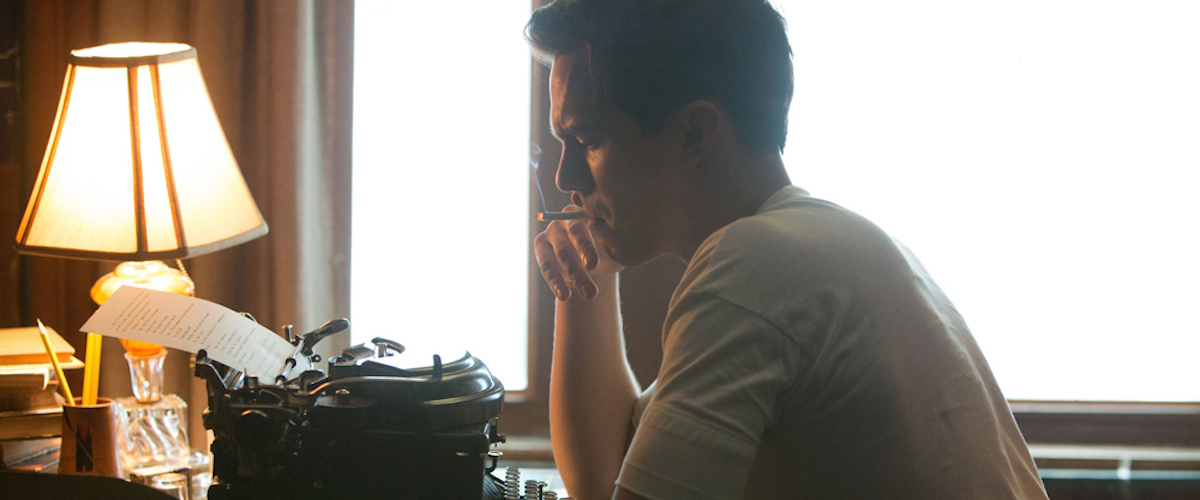

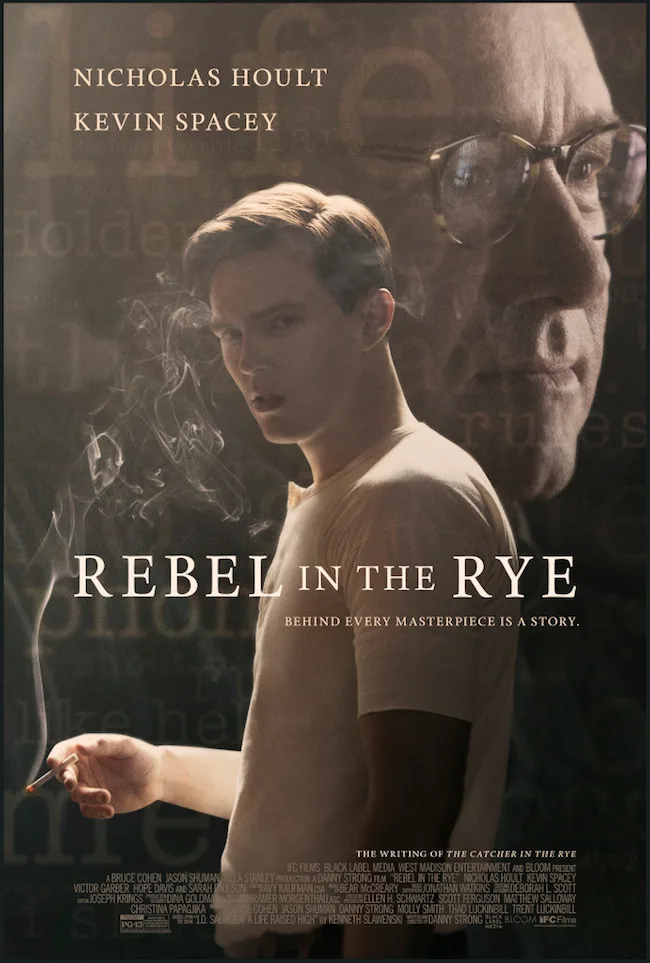

Nicholas Hoult is a gifted actor more than capable of illuminating the insecurities and fixations of his character, but he’s never quite believable as Salinger. He resembles the youthful, chiseled vision that the author likely had of himself when he stubbornly insisted that only he should be allowed to play Caulfield. Yet Hoult can only do so much with a script that leaves his key motivations frustratingly muddled. His finest moment occurs toward the end, after bidding adieu to an old friend. As he watches the man walk away, Hoult opens his mouth as if to holler out to him, before abruptly turning and exiting the frame. That fleeting nuance suggests Salinger’s desire to have said more, and one wishes the film had said more too.

The friend in this scene is Story magazine editor Whit Burnett, Salinger’s former writing teacher as well as the first person to publish the author’s work. Hoult’s lingering glance at Burnett poignantly affirms that this man was as close to a father figure as any Salinger ever encountered, certainly much more so than his maddeningly aloof old man. If “Rebel in the Rye” has any advantage over Roach’s equally flawed Oscar bait, “Trumbo,” it’s the pitch-perfect casting of its ensemble headlined by Kevin Spacey as Burnett. For the second time this year, the actor has injected a weirdly paternal warmth into an initially formidable authority figure.

As the crime boss in Edgar Wright’s “Baby Driver,” Spacey transformed gobs of exposition into a sardonic symphony, while guarding the young hero in ways both frightening and touching. I couldn’t help being reminded of the teacher Spacey played in Mimi Leder’s much-maligned yet often well-acted 2000 tearjerker, “Pay it Forward” during Burnett’s early scenes, as he simultaneously charms and challenges his students into transcending their own expectations. He believes that an author’s voice is the extension of their ego, and that a story falls apart when that voice fails to incorporate a strong narrative. The irony of this script is in how its narrative fails to incorporate Salinger’s own voice, no matter how many quotes it borrows from him. How much more powerful would the post-WWII scenes have been had they explored the specific ways in which Salinger’s war service formed the themes of his novel, much like how Laurent Bouzereau’s riveting Netflix documentary, “Five Came Back,” illustrated the impact of war on directors such as Frank Capra and William Wyler?

Caulfield’s allergy to phoniness achieves new depths of meaning in light of Salinger’s disillusioning return to the states, where he was informed that his PTSD was just a phase. It also helps explain why Salinger balked at the notion of artistic compromise, even if it resulted in his work remaining unpublished. Better to leave his writing honest and in a drawer than sanitized and read by the masses. There are several individual scenes here that are effective on their own, but they are surrounded by far too many others in which Salinger meets with a revolving door of mentors. For an alleged rebel, he sure seems willing to obey the advice of Burnett, not to mention that of his spiritual guru, Swami Nihilananda (Bernard White), and his literary agent, Dorothy Olding (Sarah Paulson, making the most of her brief screen time).

Burnett tells Salinger to turn Caulfield’s story into a novel, and he does. Nihilananda tells Salinger to remove the distraction of the city from his life, and he does. Olding approves of Salinger’s dream to write for himself rather than for his rabid fans, and the rest is history. Each of these motives are spelled out in all-too-tidy a fashion, while the more intriguing material is overlooked. We meet the high school student whose betrayal of the author is routinely blamed for his subsequent seclusion, but we never get to see what a Salinger-led youth group looks like. Also missing is a satisfactory reason for why he cruelly shut Burnett out of his life for so many years, other than pure pigheadedness. This is a glaring omission since Spacey and Hoult’s scenes together form the heart of the picture, especially when contrasted with any scene pairing Salinger with one of his lovers.

After receiving a lackluster reception at Sundance, Strong recut the film for its theatrical release, and though I didn’t view the previous cut, this one appears to be comprised of half-realized highlights from a television miniseries. Consider the grand entrance of Oona O’Neill, splendidly played by dead ringer Zoey Deutch. She’s set up as the unattainable object of Salinger’s lust, but as soon as they share a single scene together, she’s cast out of the picture before we get the chance to absorb the significance of their relationship. When Salinger arrives back home after the war, his German wife (Anna Bullard) is as much a surprise to his family as she is to the audience (whereas Deutch got one big scene, Bullard only gets one line).

As Salinger’s second wife, Lucy Boynton has a nice introductory scene where she delights Salinger with a frank put-down of his work, but it isn’t long before the infatuation fades and she turns into just another face for him to ignore. At least she gets one good line in response to her husband’s ill treatment of Burnett: “With all that meditation, you’d think you would’ve learned to forgive by now.” Alas, forgiveness isn’t always easy, especially if you’re Joyce Maynard, one of the many young female admirers Salinger reportedly seduced for sexual favors before promptly abandoning them. Perhaps “Rebel in the Rye” glosses over Salinger’s treatment of women precisely because of these disturbing claims. After all, they certainly would render the film’s stated conviction—that Salinger produced work without expecting anything in return—resoundingly phony.