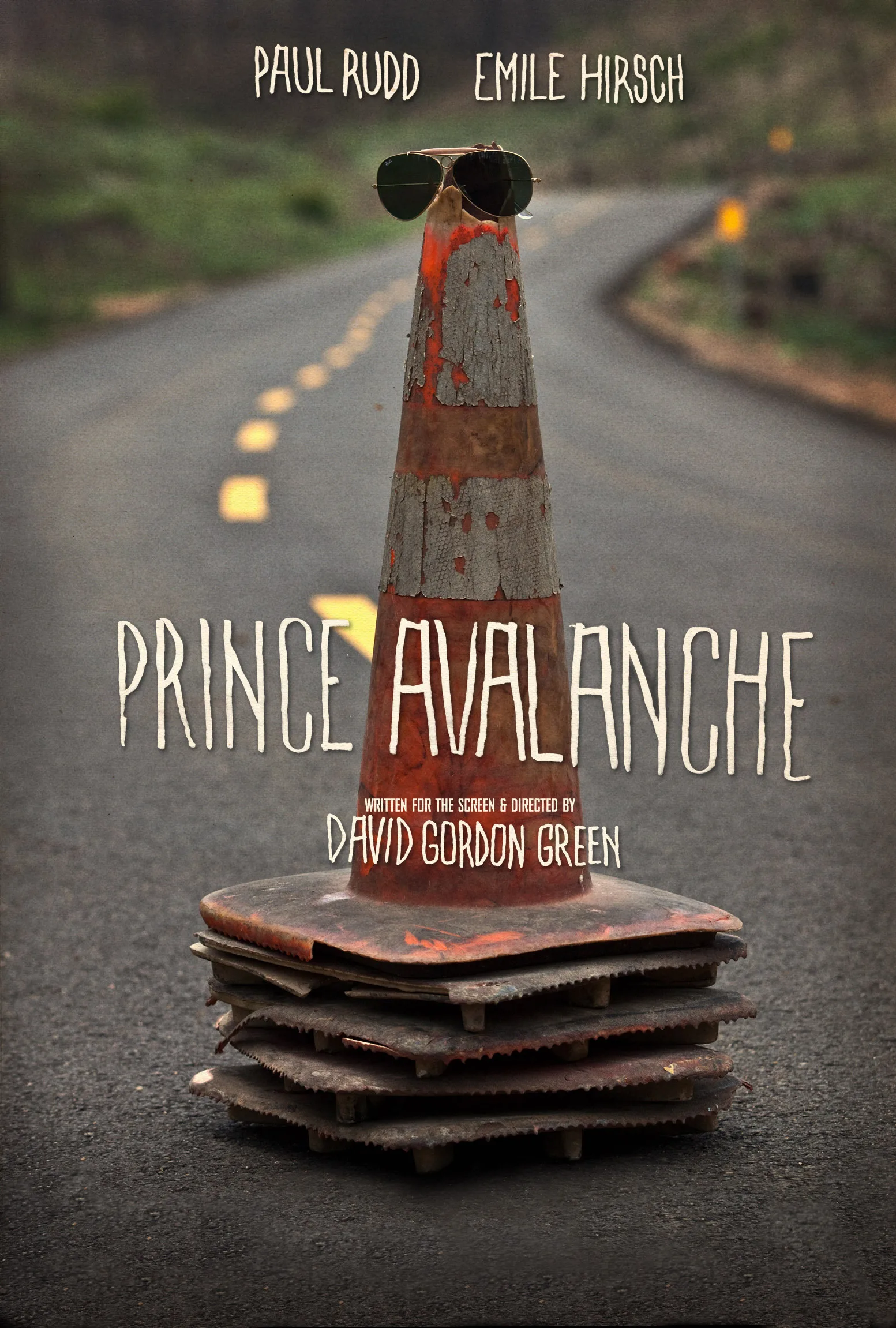

“Prince Avalanche” is the perfect end to a long summer of computer-generated spectaculars, a film in which there are only two special effects: natural beauty and human emotion.

The beauty comes from the setting: a section of landscape near Bastrop, Texas, that was scorched by wildfire. The emotion comes from the film’s main characters, Alvin (Paul Rudd) and his brother-in-law Lance (Emile Hirsch), who’ve been hired to repair land and roads. They paint yellow lanes on blacktop, mulch gardens consumed by flame, and inspect ruined homes. They kid each other as men do, keeping it light when they aren’t sniping at each other.

These early scenes are pleasant yet tense because we know what sort of movie this is—a male bonding drama that must eventually erupt into pained confrontation. When the confrontations arrive, though, the pain doesn’t feel like an obligatory story beat, because we’ve grown to know and love these characters.

At first this seems very much a mentor-pupil sort of relationship, with Rudd’s Alvin as the steady, smart, capable family man, and Hirsch’s Lance as the city kid who can’t stand being out in nature for longer than a few hours. The film’s writer and director David Gordon Green adapted this movie from the 2011 Icelandic drama “Either Way,” and there’s a touch of European style intimate-splendor to it. Swaths of flaming trees evoke the opening montage of “Apocalypse Now.” There are images of burros grazing on wildflowers, a bird pinwheeling above a line of trees, a green caterpillar inching over the top of a mossy log, yellow paint spilling into a stony riverbed, and so forth. The original score, by Explosions in the Sky, creates a trancelike feel, occasionally pushing too hard, to the point where it feels as though you’re watching the dollar-store version of “Koyaanisquatsi.”

But most of the picture has a contemplative, at times deliberately pokey groove. There may in fact not be quite enough story to support a feature—Green told RogerEbert.com’s Simon Abrams that the shooting script ran about 65 pages—but this is clearly not one of those films that loses sleep over whether every second is propulsive. In fact a large part of its worth lies in how opposed it is to the values that modern commercial films tend to prize.

This is the sort of movie that lets its two main characters spend their first few screen minutes waking up from an overnight camp, trudging uphill towards pink dawn light with shovels on their shoulders, laying yellow paint-lines on pavement, and so forth, while saying barely a word. The film reveals character through nonverbal details of gesture, framing and production design (such as when the paint-striper rolls out of frame, followed by Lance’s road-crew-inappropriate brown suede shoes).

There’s banter about the men’s “equal time boombox agreement” and chatter that reveals backstory. We get the sense that Alvin’s out here not in spite of his home situation, but because of it, and that Lance is neither the freewheeling stud nor the lazy lout that Alvin seems to think he is. Lance knows things about Alvin’s wife (Lance’s sister) that are better left unspoken, not because they reflect poorly on her, but because addressing them might puncture Alvin’s image of himself. Lance has his own blind spots. His constant droning about his pickup artistry is annoying, then pathetic, then oddly charming, because it clearly doesn’t match up with who he actually is. (When he tells Alvin he’s going to try his luck at a beauty pageant because he’s got “like, an eighty to ninety percent success rate at those places,” Alvin replies, “Somehow, in your mind, you truly do perceive yourself as a gentleman.”)

The movie made me think of one of my favorite films of the ’90s, one not many people have seen: Tom Gilroy’s “Spring Forward,” starring Liev Schrieber as a young ex-con and Ned Beatty as an older man who works in Connecticut state parks with him. Like that picture, “Prince Avalanche” feels like a stage play transplanted to the screen—there are only three major characters, the third of whom is an old truck driver (Lance LeGault) who periodically hangs out with them—and it tries to balance matter-of-fact exposition with quasi-mythological meanings. It’s the sort of film in which “We’ve got a lot of lines to paint, and it’s a very long road” is clearly about more than it seems to be about. For the most part, though, “Prince Avalanche” doesn’t push its subtext too hard, even near the end, when it becomes clear that the men are out here to repair personal as well as geographical damage.

“Prince Avalanche” represents a partial return to roots for its writer and director. Green’s first three films—”George Washington,” “All the Real Girls” and “Undertow“—were models of American art-house ingenuity, drawing heavily the work of Terrence Malick, Werner Herzog and other filmmakers who like to explore natural beauty, human psychology, and the relationship between them. Then Green took a seemingly bizarre turn into goofball stoner-bro comedies: “Pineapple Express” and “Your Highness.” But as Christy Lemire points out in her profile of Green, this wasn’t a case of a filmmaker abandoning his gifts to make something commercial: the two modes represented different aspects of Green’s interest. One of the many fascinating things about “Prince Avalanche” is how it merges those two types of films with understated grace.

The bickering and manly preening and childish yet hurtful insults, the farting and scratching and other base gestures, and the expertly staged physical comedy (some of which seems to have been improvised) have that ’80s comedy feel that Green loves. But the picture’s vibe is pure arthouse visionary, channelling Herzog, Malick and the dramas that Gus van Sant made in the aughts (particularly “Gerry“).

Green displays a similarly adventurous yet kind spirit here. The most powerful scene is one of the subtlest: Alvin talking to a woman named Joyce Payne, whose home was destroyed by the blaze. Payne is a real-life fire survivor, and that was actually her house. Green and the crew met her during filmmaking and thought it would be nice to work her into the movie. “This is your house,” Alvin says. “Was,” she corrects him. “Everything’s past tense now.” She tells him she used to be a pilot, and wonders how “anybody’s gonna prove that I had all these experiences, and flying.” She tells him he’s looking for her pilot’s license. “Do you think it burned up?” Alvin says. “I guess so,” she replies.

Alvin goes into an adjacent ruin and walks around. He pretends it’s a functioning house with people in it, and that perhaps his wife is there and is glad to see him. It’s an impressive bit of Chaplin-eseque pantomime by Rudd, who’s a revelation in this film, but there’s more going on here than a bravura display. Something deep is roiling within this man, something he can’t let out. We live in our illusions. We don’t want to leave them.